The Logic of Jarring in Julia Cohen’s I Was Not Born

Julia Cohen’s collection I Was Not Born (Noemi, 2014) lives in the cleft between lyric essay and long-form poem. This at-once fractured and mythic narrative takes as its central drive the something that unfolds between two bodies when one of those bodies is dealing with the impulse of suicide. It is the story of N. and J., who fail, both independently and together. It is also the story of how that story unfolds, for J., our narrator, both confesses and withholds as she copes with the impossible task of telling.

Julia Cohen’s collection I Was Not Born (Noemi, 2014) lives in the cleft between lyric essay and long-form poem. This at-once fractured and mythic narrative takes as its central drive the something that unfolds between two bodies when one of those bodies is dealing with the impulse of suicide. It is the story of N. and J., who fail, both independently and together. It is also the story of how that story unfolds, for J., our narrator, both confesses and withholds as she copes with the impossible task of telling.

To say more than that about the story in I Was Not Born would be to populate voids that are very intentionally left empty, as we are not offered a comfortable arc with which to see a pair of people uniting or coming apart. Rather, the narrative follows the laws of collage, where juxtaposition is used to illustrate contradiction and echo. For example:

Jar the crab legs. Jar the white stones. Jar the chrysalis but punch holes through the lid. Jar the sparklers into smoke. Jar my cough. Give me back a pulse. Give me back my pile of paper. My clothing, clean hair. I am sitting on the stairwell is sickness, in pale face, in fragile gown, listening to dinner clink below. I drink juice, swallow ten pills at a time. I was taught to fight this body & no one told me how to stop.

The collection—which provides essays that live independently but also collect to craft a body of prose that explores themes as varied as illness, love, selfhood, and art—is bookended with two longer essays in which we are offered therapy transcripts of a discussion between J. and “Dr.” These interviews work to ground the more lyric and exploratory essays in the very concrete reality of dealing with a traumatized partner, ultimately producing a rich tension between aestheticizing the story and recording the ugly facts. The transcripts, which are highly performative in their employment of colloquial speech, live in stark contrast to the intense privacy practiced in the more poetic places, and calls to mind both the plays of Nelly Sachs—a figure who haunts the book as another woman dealing with a suicidal partner, Paul Celan—and the Socratic dialogue that has become so closely associated with asking questions not necessarily in service of finding answers.

This toggling between moments of grounding realism (“N. introduces me to H.D. & Deleuze, to riding a bike as an adult, to multiple orgasms, to broccoli rabe sandwiches & homemade sauerkraut”) and ontological questions about self and art (“What is a minor person?” “Do I live the way I read?”), suggest that the book adopts the narrative logic of the verb jar. Here jar has two, perhaps contradictory, meanings: to withhold and contain inside a closed space, and also to rupture the familiar through surprise. In this way, we read “if you have patience, jar it” both ways: keep your patience confined and also disrupt it. This is how the book itself jars; it is an attempt to collect and enclose the violent circumstances of living with a suicidal partner through recording and it is also a celebration of the refreshing possibilities of art that embraces instability and dis-ease.

As our narrator says, “Sickness takes a certain kind of patience.” Later she provides an example of the wait:

Who can pay attention the longest? So many songs come from the shower. Laminate leaves or clean out the drain, the grapes, the fury of its avenging families. Flies cling to memory like a cenotaph. Say aaaaah. Say ache.

What is revealed in this short excerpt is the rich possibility that resonates in that twilight space between sentences. A prose artist might desire to close this cavity, to permit bridges to surface where the gaps loom distant. But a poet working in prose here offers few bridges, requesting instead we jump and in jumping, risk. Or, to provide a metaphor more appropriate to Cohen’s uptake, the space between the sentences act like split skin, where the reader’s work is to suture the flesh of the story together. And this is how the book embraces a beautiful array of paradoxes; it is a narrative that offers somehow both a rough scaffolding and an empty casing, the bone frame and loose skin. Here the reader becomes not an audience for but an agent in the making of meaning, for those authorities on disorder in the body—doctors—repeatedly fold. “Say aaaaah,” our speaker demands, in effect requesting we open our mouth in service of the story. “Say ache,” our speaker demands. The book is both literally speaking the word “ache” (ten of its twenty-one parts are titled “The Ache The Ache”) but also—perhaps more so—the book itself is, like heartache or headache, literally suffering from sayache, or the pain that escorts the work of telling.

This ache-in-saying is made most clear in what I might argue is the book’s central conundrum; this is, How do we narrate the story of a human’s desire to end his own life? Or, perhaps more accurately: how do we narrate the story of beholding a human’s desire to end his own life, a human whom we happen to love? How do we narrate the attempt? Not incidentally, of course, the word “essay” comes from the Latin for “to try.” It might be that the only form willing to take on such a grave task is the essay.

If I Was Not Born is an object study in the art of jarring, it succeeds; not only does the book serve as a vessel for the haunted reality of locating the place where the self ends, but it is also an encounter with the suddenness of the unexpected. There is a poignant tension at work here between loitering in the present, arrested by the poem, and moving ever-forward through time, propelled by the story. The paradox performed by at-once feeling suspended and feeling compelled to advance is one at the center of perhaps our most complex human emotion: grief. Here Cohen performs grief to its exhaustion, and we, in reading, participate in “the ache the ache,” both riveted and troubled in the healthiest way.

“How to prolong the lyric moment?” Carole Maso asks in her essay, “Notes of a Lyric Artist Working in Prose.” The answer is Julia Cohen’s I Was Not Born.

Seven Days: A Review of Nick Courtright's Let There Be Light

Mourning lost divinity is hard to tire of. Repetition only demonstrates its relevance. Thus the chiaroscuro longing of “Assomption de la Vierge,” sets a fitting mood for a book that starts in the modern moment and traces back through cosmo-biblical time

Mourning lost divinity is hard to tire of. Repetition only demonstrates its relevance. Thus the chiaroscuro longing of “Assomption de la Vierge,” sets a fitting mood for a book that starts in the modern moment and traces back through cosmo-biblical time.

The Virgin Mary has left the frame of Earth. Rapacious hands remain. Granted, the Virgin is not the Godhead. She is the goose that laid the golden egg. There are other egg-layings in this book. Beings emerge into the now, as if laying their own eggs, chrysalis-like, but with a mathematical stop-animation immediacy, as the time-step goes to zero. An egret begets itself from one moment to the next. We are asked to ponder its ontology through the infinite parcels of time.

In his latest book, Let There Be Light, Nick Courtright takes the time step beyond zero, going into negative intervals. This narrative traces back through 14 billion years and 7 biblical days in a varied collection of verse, discussing the death of stray cats, lyrical bridge crossings, cosmic background radiation, animal hunger, and the like.

Some stylistic choices provide obstacles in that path: endings are often unsatisfactory and ellipses are serially inserted. But these frustrations withstanding, the body of work provides a compelling meditation on the inflorescence of time and the senescent circumstances of modernity, in a cosmo-eco-biblical fullness found few places in verse.

Particularly satisfying are the lyrical modes pushing out against the time-conscious themes of this book. For example, the flagship poem “The Big Bang”, features “a finch making its sound from inside of joy,” an occurrence which only arises after the quanta of days, hours, seconds, weeks have been abandoned. “I thought, this, a day, is not a fraction I have to recognize / … nor the other products of separation.” The tweeting is brief, and its sound is enveloped by the surrounding rush of time, as if a wind. But still, it fights against that wind.

This is what good poems do, like finches: they expand the realm of the now, pushing out against the flow of time. Courtright does that in a poem about departure:

I walk through the front door, and you say

One day you will wake to find yourself finished.I walk through the front door. Look at the time,

you say. Look at the time.Your bags and my thousand flaming trees are full.

Hills fall over each other, rumpling their outfits.

“Look at the time” works ironically: the season and this relationship are late in their course, yes, but the moment commands more than its allotted span of minutes. In that sense, “Look at the time” says: I’d rather not talk to you anymore. Departures such as this become a part of the eternal present-moment for the grieving remnant. In this way, endings in this book can serve as fundamental lyric: when a sequence is cut short, it enters into a timelessness where all the preceding events are enshrined.

But the lyric that holds most prominence in this book occurs at the beginning of time. It is the ineffable presence of super-compressed proto-matter that exists before the big bang. This reservoir, immune to time’s arrow, mirrors a pre-expulsion Eden, mirrors the first day of a child’s life where everything is new, mirrors and presages every other lyric which pauses in the present while future potencies bide their time.

This Edenic lyric persists in fragments: angelic egrets stand guard as symbol and flag; a traveler pauses mid-bridge and sings reassurance to herself; riparian thought abides in black-faced gulls and barges that “pour their enormous stomachs across the river.” Time still flows in these echo-lyrics, but at a pace that suggests infinitude and continuity with all previous moments. It is worth dwelling in such moments, and Courtright’s incessant reminder of time’s cruelty empowers us to do just that.

The scientific perspective is key to knowing such cruelty, and Courtright uses it efficiently for that purpose. In a poem titled “Intelligent Design,” Courtright maps the age of the Universe against the metric of human existence. In “Lost on Planet Earth,” Earthworms move the terrain beneath our feet, making it suddenly new and alien when we look down again. This is what Courtright calls us to do repeatedly: to look down at the Earth that has changed and ask, “Is this okay?” instead of “and God saw that it was good.”

Consider, in turn, the romantic longing that the cosmic in this collection provokes. In “The Deep,” the faint electromagnetic hum from the big bang – i.e. cosmic background radiation – is presented as “a phone ring[ing] unanswered into the vast universe.”

“Please, please eternity, leave your message –” the speaker pleads.

In this despair, Courtright’s own plea for the lyric rings out in the space of this collection. It is a thrilling meditation on the form, one which presents many sounds of the immutable and the corrupted.

Skynet Becomes Self-Aware At 2:14 A.M. Eastern Time, August 29th

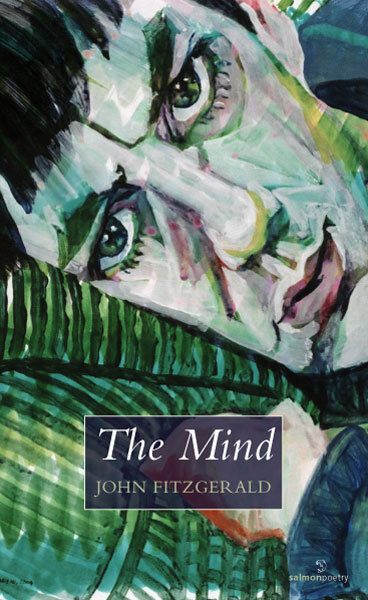

If I were teaching from John’s book, I would encourage poetry students to examine his masterful skill with personification. I would encourage philosophy students to wrestle with his experiences of phenomena. I would ask psychology and neurobiology candidates to experience the brain from inside-out.

If I were still working with John Fitzgerald (in the interest of full disclosure, we worked together at Red Hen Press), I would nudge him and say of his book THE MIND, “Skynet becomes self-aware at 2:14 a.m. Eastern time, August 29th.”

My sense of John is that he has been aware of himself for a long time, but not in a solipsistic or narcissistic way at all. He is a keen observer, a consumer of origins, fine distinctions, continua, grand schemes, and minute details. He likely began observing and contemplating information from the moment he experienced the glare of light in the delivery room, and he has never stopped.

Interestingly, while THE MIND is about the remarkable way John thinks, it speaks to the larger questions of how we all think, how we came to be sapient in the first place, and how we develop as thinking souls in space and time. Keeping the language of his prose-like tercets basic, unadorned, and free-flowing, he accomplishes poetry of significance and elemental beauty. Left brain contemplation of structure and systems aligns itself with right brain wonder and whimsy, but neither hemisphere dominates in the work, so the reader can only expect the unexpected. And the rewards are great: poems of curiosity, orientation with the universe, sorrow, finding center, and surprising hilarity. (Only John can make the idea of rocks funny.)

If I were teaching from John’s book, I would encourage poetry students to examine his masterful skill with personification. I would encourage philosophy students to wrestle with his experiences of phenomena. I would ask psychology and neurobiology candidates to experience the brain from inside-out. I would ask physics students to explore how we process space and time in an era when such concepts are continually challenged and updated. I would ask divinity students to consider creation from the point of view of the created. THE MIND weighs so many approaches to thinking and being that you won’t devour it in one or two sittings. Read it as you would the Book of Genesis, or Hawking, or an introduction to meditation. You will not think the same way ever again after reading it.

Love Is the Greatest Threat: A Review of Jane Shapiro's The Dangerous Husband

The Dangerous Husband by Jane Shapiro is the predecessor of Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn, a marital thriller that amuses itself with unexpected turns of phrase and wiles away the hours by punishing the reader’s loyalty.

The Dangerous Husband by Jane Shapiro is the predecessor of Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn, a marital thriller that amuses itself with unexpected turns of phrase and wiles away the hours by punishing the reader’s loyalty.

“Help me,” he said in greeting. “I’m in a mess.”

“I’m not the one to save you!” I snapped, and we laughed like maniacs.

This conversation, the book’s meet cute, takes place in a surreal landscape that uncomfortably echoes our own, where love is the greatest threat to future happiness. An unnamed woman marries a hunky oaf named Dennis who turns out to be a terminal klutz, causing her to fear for her cat, him, her frog and her own life. The woman hires a hit man and vacillates on whether someone so prone to unhealthy mistakes with permanent consequences should be permitted to blunder about in the world.

A funny book about a serious subject that delights in its unreliable narrator and her oddly believable husband. Is the abuse accidental? Are you privy to the marital secrets on the pages or are they not secrets at all? How familiar is all of it and how does that correlate to its level of funniness? Is accidental abuse still abuse? Does original intent alter the crime? Is it no longer a crime, now relegated to a mere mistake, no matter how painful?

The best part of the book is Shapiro’s bland descriptions of the way disenchantment tends to creeps up on a person, even as complacency takes over and mildly boring routine becomes the new order. What was once disarming has decayed into the unforgivable, what was once irksome now intolerable, and what was once possible to overlook is now all that can be seen.

Despite its indulgently pretentious tone The Dangerous Husband is imminently readable. It is a darkly comic, self-aware, postfeminist portrayal of a marriage falling apart. And staying together. And getting hurt. And falling apart again. So we greet and snap and laugh like maniacs because what else is there to do?

On Delmore Schwartz’s The Ego is Always at the Wheel

A century after his birth, and nearly fifty years since he died, alone, in a midtown Manhattan hotel, Delmore Schwartz, briefly considered the great American poet, remains relatively unknown. Hailed by the likes of Nabokov, Eliot, Bellow and Trilling, Schwartz remains relatively absent from the Elysian Fields of the Forgotten Author: The syllabus.

A century after his birth, and nearly fifty years since he died, alone, in a midtown Manhattan hotel, Delmore Schwartz, briefly considered the great American poet, remains relatively unknown. Hailed by the likes of Nabokov, Eliot, Bellow and Trilling, Schwartz remains relatively absent from the Elysian Fields of the Forgotten Author: The syllabus. Not even New Directions’ 2012 reissue of his story collection, In Dreams Begin Responsibilities, revived Schwartz. Perhaps admirers were misguided in their attempted revivals. For it’s no longer the stories readers want, but the stories about the creators of stories, the interviews, origin tales, and advice to the novices. But in The Ego is Always at the Wheel—Schwartz’s undeservedly neglected personal essay collection—we find just that. Here he mythologizes, criticizes, sketches, and yarns to create a lucid and neurotic account of the role of the Artist.

Schwartz was a tormented genius. A literary Icarus; as much reputation as writer. That he wrote feels both fundamental and incidental to his biography. He made his name through his writing, but now it’s the torment interests us—posterity loves splitting authors into their work and their torment. But The Ego is a synthesis. It’s an account of Schwartz rendered by Schwartz: a deft construction distinct from the triangulation of journal, biography, and fictional alter egos. This is the public persona. Not the medicated melancholic who cataloged his drinks in his journal. Not the man who stole his wife’s typewriter because his work was more important than hers. Not the pill-popper who lay unclaimed at the morgue for three days. Here is the witty and humorous Delmore who left friends breathless with laughter. The man whose company “meant not only breathing with one’s lungs but with one’s mind.” The man whose death stopped clocks.

The collection’s longest piece, “Memoirs of a Metropolitan Child, Memoirs of a Giants Fan,” is a sort of bildungsroman squeezed into 22 pages. As a young man, Schwartz intended to split his adult as a New York Giants short stop and a poet—that is until he reads The Decline of the West. The book devastates him. “By New Year’s Day the Spenglerian sky . . . made the new year seem as hopeless and bleak as my own present and future.” He feels as if he were “born too late in a world too old.” If the West is in decline, he reasons, why do anything? Why be a poet? For the fame? Schwartz does, after all, publish poems in his high school literary journal—only to learn that nobody reads them. In the essay, Schwartz confronts the insecurity and fatalism of a young poet—the belief that he will never be good enough—as it clashes with the fantasy that poet need only work hard to succeed. Newspaper “reports of boy wonders and child prodigies”depress Schwartz. Talent is linked to genetics: “Was your father a poet? Was your grandfather a poet?” an uncle asks. They weren’t. So how can Delmore become one? The irony is thick. Reading the essay, we know that Schwartz, the son of no poets, became a great a poet. This provides a veneer of comfort (We really can become anything with enough work!) that Schwartz masterfully undercuts when he concludes “Experience has taught me nothing.” If he has learned nothing from experience, what can we learn from reading this essay? The essay isn’t advice for how a writer should be, but merely what happened.

The intersection of literature and personal life found in “Memoirs” reappears throughout the collection, notably in its literary criticism. In, “Hamlet, or There is Something Wrong with Everyone,” Schwartz begins by summarizing the play with the arrogance of a tenth-grader: “Ophelia was very much in love with Hamlet, and when Hamlet went to Germany to study metaphysics and lager beer, she thought about him all the time.” He dismisses a variety of scholarly readings—Hamlet was a woman, he was homosexual, everyone was blasted drunk—and concludes that Hamlet was manic-depressive. “No one knows the real causes of the manic-depressive disease . . . and that is why no one understands Hamlet,” he writes, with an urgency belying personal struggles with bipolar disorder. “You can have this gift or that disease, and no one understands why, no one is responsible . . . and yet no one can stop thinking that someone is to blame.” Like the disappointments of youth in “Memoirs,” Hamlet is used to confront a larger question: Can we, and should we, relate to great literature? Schwartz studies the play in order to understand Hamlet, with whom he has an affinity, but Hamlet cannot be understood. Associating with Hamlet means being misunderstood. It means having a gift and feeling like someone’s to blame. There are dangers, the essay suggests, in relating to art.

Yet his personal life is inextricable from literature. Where Schwartz, in his journals, might find despair in this fact, the author of The Ego plays it for comedy. In one essay, his nine-year-old brother-in-law advises him to give up writing and become a golf caddy—a comparably lucrative option he briefly considers. Asked by a reporter why he became a poet, Schwartz answers, “as an infant in the cradle I had cried loudly and received immediate attention . . . I tried crying out loudly in public and in blank verse, and the results had on the whole been most gratifying.” Attempting to define existentialism, Schwartz evades the facile definition that we are all alone and must die alone, to conclude that existentialism quite simply means “no one else can take a bath for you.” And in “Dostoyevsky and the Bell Telephone Company,” Schwartz teaches The Brothers Karamozov to Bell Telephone executives. Invited out for drinks after class, he surprises his students by accepting. “There seems to be some misunderstanding about those who read books having no time for guzzling,” he writes, “no class of people are more abundantly provided with time for drinking than readers of books.” Amen.

And we find Schwartz at his best when he writes directly about the relation between poet and audience. In “Poetry is Its Own Reward,” he reflects:

Every modern poet would like to be direct, lucid, and immediately intelligible, at least most of the time. In fact, one of the most fantastic misconceptions of modern literature and modern art in general is the widespread delusion that the modern artist does not want and would not like a vast popular audience. . . . The lack of popularity does not arise from any poet’s desire to punish himself of these glorious prizes and delectable rewards. The basic cause is a consciousness of the powers and possibilities of language, a consciousness of which cannot be discarded with any more ease than one can regain one’s innocence.

The desire for fame tormented Schwartz throughout his career—he began his career “passionate

with reveries of glory and power.” But as his notoriety waned, he took greater solace in the act of writing, seeing the work, rather than public attention, as poetry’s primary reward. Was this a rationalization, coming from a writer who so dearly craved adulation? Mastery is, after all, the final refuge for the unread author.

Throughout these essays Schwartz tries to understand, quite simply, how a should writer be in the world. This remains a problem today—recognizable not only in the myriad craft books pawning the trade, but in the brilliant work of Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, or Karl Ove Knausgaard. The ubiquity of writing advice and interviews from authors of varying talents puts writers in contact and conflict with an ideal Author. Writer and Author endanger one another, like a yin and a yang vying for space on the circle. Facing this same problem, Schwartz asks a friend if he would rather write great poems or be a poet? Is it best to be a writer, he asks, or a celebrity? And when, we might ask ourselves now, do we cease being the former and became the latter? Do we even notice?

Although it’s hard to tell what Delmore would say about the state of American letters, with its domesticated fabulists, its MFA industry, and its click-bait existential crises, the essays in The Ego come close providing an answer. The collection is reminiscent of Roberto Bolaño’s Between Parentheses, with its lucid digressiveness, casual tone, and glib pronouncements. And the book shares many qualities with David Lipsky’s Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, where we see Dave Wallace playing the part of David Foster Wallace. The Ego is Always at the Wheel is a fascinating, funny, and sly self-portrait of an artist due for a renaissance.

We Are Conditioned, We Are Conditional: On Cassandra Troyan's Blacken Me Blacken Me Growled

I first read Blacken Me Blacken Me Growled in pdf form while at my desk at work under the glare of one thousand fluorescent lights, Cassandra’s words fantastically magnified on the computer monitor. I felt odd and more than a little disoriented. Where did the poems start? Where did they end? And were the black pages poems too, or titles, or something else, some other, unnameable art form altogether?

‘If we’d only stop flailing

we’d realize we float.’

I first read Blacken Me Blacken Me Growled in pdf form while at my desk at work under the glare of one thousand fluorescent lights, Cassandra’s words fantastically magnified on the computer monitor. I felt odd and more than a little disoriented. Where did the poems start? Where did they end? And were the black pages poems too, or titles, or something else, some other, unnameable art form altogether? I scrolled and read, the poems blurring together into an kind of melancholic state. After “Shells,” part three of four (following “Carriages” and “Chambers,” and preceding “Hides”), I needed a break. Plus, my shift had ended at 11 pm and I was the only living person still sitting in the office.

My fiancé had been writing in a Burger King down the street, and on our way home he asked me about Cassandra’s book. Was I enjoying it? How did the poems compare to Cassandra’s poetry circa 2011 (an energetic and exciting time for me in the internet writing scene, during which I devoured anything and everything Cassandra Troyan had published online and wildly and more often than not drunkenly asserted to anyone who would listen that she was one of THE BEST poets I knew)? Responding to these questions was difficult. They were different, I said. I didn’t know, I said. What did these poems make me feel? I couldn’t say. Was I different now? Was Cassandra? Maybe we had both changed in ways that disconnected us as ideal writer / reader. I felt sad.

First thing the next morning, I sat in bed and read “Hides” on my laptop, and everything changed. Here it was, for me. I found purchase in these poems, was immediately drawn to the space they took up on the page, their breadth and their intensity. Cassandra begins:

Now I would like to play the role of provider / inviter

of supreme romance supreme terror

Yes, I thought. Yes, yes, yes, I continued to think as I binge-read the last 50 pages of Blacken Me Blacken Me Growled. What was so different about “Hides”? Or, what was so different about my reading of “Hides”?

1. I felt more comfortable while reading “Hides.” Sitting in my bed, my house enveloped by rain clouds (I live at the top of a hill overlooking the city), reading off my laptop in natural lighting gave me sense of control over my environment I hadn’t had in my office.

2. “Hides” begins with an epigraph from Lorrie Moore’s A Gate at the Stairs that made me feel ‘same’:

The juddering of climax, as involuntary as a death rattle, I took to be a statement of hopeless attachment. Why, I don’t know. I didn’t think of myself as sentimental, I thought of myself as spiritually alert.

3. The sexuality and brutality in this section felt like a huge throwback to Cassandra’s poetry circa 2011, which I had felt connected to then in a very intense way (I had ‘taken a lover’ who was mentally and physically exhausting me, in unequal parts dangerous and wonderful. Cassandra’s writing made me feel like I was part of some kind of club of poets writing about sex and sexuality in an empowering way.)

4. Everything fell into place, aesthetically. The black pages felt less like title cards here and more like poster poems, like,

I WANT EVERYTHING TO HURT MORE THAN IT NEEDS TO AND SOMETIMES YOU JUST GOTTA BEAT THAT PUSSY UP

stands alone, I think, but also acts as a kind of conversation starter for the poem that follows, which begins:

“What does that mean in terms of / sexual gratification / exchanges of diversions / distracted tongue”

5. There is so much scary beauty here.

Hides made me feel nostalgic and excited. It also made me want to immediately reread Blacken Me Blacken Me Growled, which I did, which felt like an entirely different experience than it had when I read the first three sections.

People change. But the thing is, we don’t just change over long swaths of time (which is what three years can feel like to a 26-year-old human with a heightened sense of her own impermanence), we change from setting to setting, from day to day, from condition to condition, and these conditions can drastically change something as simple or as difficult as reading a pdf of an old friend’s new book. These conditions can change our connections to the world and our home and ourselves. Find your right conditions and Blacken Me Blacken Me Growled will meet you there.

Discovery: A Repetitive Process

Leonora Carrington’s book, The Hearing Trumpet, like her artwork, is strange in an oddly beautiful way: “Houses are really bodies. We connect ourselves with walls, roofs, and objects just as we hang onto our livers, skeletons, flesh and bloodstream.” Sentences like this make me want to read this book forever. I feel connected to the words as if I’m living inside of them and they are living inside of me.

Leonora Carrington first appeared to me by way of a painting entitled, “Eluhim” or ‘gods’ in Hebrew, on a visit to the Tate Modern in London about a year ago. Her art is strange, not like Dali or Picasso, strange in a slightly fairytale yet disturbing way, a hard to pin it down way. The painting I saw there used muted colors, lots of taupe and gray possibly a way to express neutrality and a matter of fact-ness about the subject matter. Something haunted me about this strange piece of art. I vowed to learn more about her when I got back to the states. I arrived back home ten days later, but I had already moved on to other things, unpacking, finishing an Anne Enright book, with a very steamy opening chapter.

Six months later I found myself traveling to Evanston, IL with my boyfriend to visit his family. I had moved on to another book, one that I won’t name because I couldn’t finish reading it. Chicago, or “the city” as Evanstonians say, was just minutes away. One afternoon we made our way to the Chicago Art Institute where I ran into Carrington again. Her work entitled Juan Soriano De Lacandón also used a neutral color palette and unsettled me in much the same way as the piece I saw in England. This time my curiosity grew and again I vowed not to forget about her.

This time when I got back to Oregon I had not forgotten about Carrington. I Googled her. First, I looked at the images tab in the search. Lots of photos of her artwork showed up, but also a couple images of a very serious woman looking at the camera in a way that made you wonder what she had seen in her life to make her look this way. A very different reality from what many of her paintings depict, but also unsettling just like her artwork. Then I found a web page and read –“A British-born Mexican artist, a surrealist painter and a novelist.” I read about how she was an outcast in the Catholic school she attended, but that she decided to go on and become an artist and later a writer. A writer. This, I had to check out.

Leonora Carrington’s book, The Hearing Trumpet, like her artwork, is strange in an oddly beautiful way: “Houses are really bodies. We connect ourselves with walls, roofs, and objects just as we hang onto our livers, skeletons, flesh and bloodstream.” Sentences like this make me want to read this book forever. I feel connected to the words as if I’m living inside of them and they are living inside of me.

The Hearing Trumpet is the story of a 92 year old woman, Marian Leatherby who receives a hearing trumpet as a present from her friend, Carmella, a woman who is her conspirator, a trusted council, and ultimately her rescuer. It’s a story about the power of friendship and a story of their irreverence in the best way possible. The friendship in this novel is one of the most heartwarming aspects of the book and one of the reasons that I wish I owned it. It was inspired by Leonora Carrington’s close friendship with fellow painter Remedios Varo. I wish I had known Carrington or at least had gotten to see her read, but she passed away in her 90’s in 2011.

One of the best things about the book was that it was about an age group that I don’t see a lot in the novels I read. They were all spunky elderly women who had been pushed out of their children’s homes because they needed a bit more looking after once they began to age. Of this age group she says, “People under seventy and over seven are very unreliable if they are not cats.” Phrases like this make the book come alive. The book starts to delve into a more fairytale realm in the latter half and then things get wild, in a good way. I went along for the ride and I’m glad I did.