Memory vs. Truth: a Review of Oliver’s Travels by Clifford Garstang

As Ollie develops Oliver’s character, anyone who has attended a freshman creative writing workshop will be amused to recognize the young writer trope of prosaic fantasy-fulfillment, the way a twenty year-old reveals their gushiest visions of their ideal selves, while casting love interests as props to their main character’s self-discovery.

All novels are mystery novels, a seasoned author tells hopeful writer, Ollie. At the core of everything we read about a character is their greatest desire. The mystery, as in real life, is what will the character do, and to what lengths will they go to attain this desire?

Ollie’s desire is multifold: his most urgent need is to find his Uncle Scotty, and ask him why Ollie is haunted by childhood memories related to him. Underneath this urge runs the very familiar, existential dread of the recently graduated. But in Ollie’s case, this includes the question of his sexuality. In Oliver’s Travels, Clifford Garstang interrogates the folly of memory and meaning through a deeply flawed, possibly traumatized, occasionally problematic main character, asking, how do we know a thing, or how do we come to accept something as known?

Oliver’s Travels is indeed about travel, including the travels Ollie should have taken; “I should have gone west, like the man said,” the novel opens. But rather than follow this romantic cliché of young adulthood, Ollie does what many young people are forced to: move back in with a parent. At first it is in Indianapolis, with his divorced father and “wounded warrior” brother, Q in the house where Ollie grew up. One day, Ollie is looking through family photographs when he becomes curious about his father’s estranged younger brother, Scotty. His father tells him Scotty is dead. His mother tells him Scotty is dead. Neither of his siblings, Q or Sally-Ann can recall what happened to him. But Ollie’s memories of his adventurous uncle, and his lack of memory of his death, point to different conclusions.

When staying with his father becomes unbearable, Ollie moves in with his mother in Virginia. Once again, he fails to go west. He admits, “I’m deficient in the courage department.” There Ollie accepts a job as an adjunct professor of English at a community college. He meets another teacher, a prim young lady wearing a cross necklace named, appropriately, Mary, whom Ollie begins half-heartedly dating. Immediately he begins projecting a version of himself that he suspects she wants: a passionate teacher, and a nice guy certain of his future.

But Ollie is anything but certain of his future. What will he do with a degree in Philosophy? He realizes he greatly misses the structure and challenge of school. He was inspired by his relationship with one professor in particular, which ended abruptly. Yet the influence of Professor Russell is clearly embedded in Ollie’s consciousness, as Ollie’s chronological narrative is interspersed with his memories of the professor’s lectures and their meditation sessions.

Meanwhile, Mary and Ollie are all wrong for each other. They disagree on nearly everything, with little crossover in interests and tastes, to a comical degree. Ollie is a wimp and Mary is a ninny. As such, their convergence only makes sense, the one too scared to leave the other, despite their obvious incompatibility. Mary, he thinks, represents things he should want: a nice, churchgoing girl who reads books (albeit not “good” ones), plays piano, sings “like a Siren,” and knows she wants to be a teacher, a wife and a mother. She has also continued living with her parents for three years after graduation, a thought that is mortifying to Ollie. But when he meets her brother, Mike, suddenly Ollie wants to spend as much time with Mary as possible. Why can he not get him out of his mind, Ollie wonders? And does it have to do with his patchy memories of Uncle Scotty?

Since cowardice and indecision render him incapable of running the trodden path of young male fortune-seekers, Ollie lives out his fantasies another way: on the page. He invents “Oliver,” an alter-ego who possesses the adventurous spirit Ollie lacks, journeying to distant lands with an “exotic” woman by his side. As Ollie develops Oliver’s character, anyone who has attended a freshman creative writing workshop will be amused to recognize the young writer trope of prosaic fantasy-fulfillment, the way a twenty year-old reveals their gushiest visions of their ideal selves, while casting love interests as props to their main character’s self-discovery. With characters’ names barely changed from their counterparts (“Oliver” and “Maria”), Ollie re-imagines himself as charming and courageous, and Mary as exciting and dangerous. It is at times agonizing (read: triggering) to watch as a scared young man wastes an ambitious young woman’s time, abusing her trust while he figures himself out. And yet Mary may have a secret or two of her own. Meanwhile, the possibility of his childhood trauma looms heavily over Ollie. We are beckoned, if not compelled, to give him a break.

Ollie’s relationship with his father is especially pertinent to his wavering confidence. Ollie was born with only four toes on each foot, a harmless expression of some genetic trait. “One of the clearest memories I have of my childhood,” Ollie recalls, “is my father’s insistence that I wear something on my feet while in his presence–socks, shoes, slippers.” When one day young Ollie compares his number of toes to his brother’s, he finally notices the discrepancy and begins to cry. “But it wasn’t the missing toes I was crying about. I had finally understood why my father hated me.” Reading Ollie as a possibly-not-heterosexual character, this strikes an especially emotional note, as he realizes his father hates him not for his choices, but for the way he was born.

As snippets of his childhood return to Ollie, he wrestles with the imperfect and erratic nature of memory and truth. If others have no memory of an event, and your own is patchy, did it happen to you at all?

Ollie and Mary have a memorable (and cringe-worthy) fight related to the nature of memory, faith, and truth. A shaken Mary confides in Ollie when a student of hers tells her she has just been sexually assaulted. In response, Ollie enters interrogation mode: “So she called the cops? Went to the hospital? No? Why the hell not?” He questions whether or not she would have reason to lie (Mary has said the student is prone to embellishment in her essays, she had an exam that day, etc). He suggests that “maybe she needs some attention.” One wishes a tug on the ear could make him shut up as he presses on. Surely no one could be so oblivious, so lacking in emotional intelligence, as to not recognize the real stakes in the conversation (i.e. his relationship with Mary).

To her credit, Mary reminds him of the emotional nuances of sexual trauma, and even introduces him to the student in person. But this backfires, as Ollie doubles down on the issue of the student not reporting her attack to the police. “If you don’t,” he warns her, “. . . eventually even you will begin to doubt that it happened. It will fade from reality and become just a bad dream.” The fight illustrates Ollie’s attitude towards his own trauma: if certain facts are not known, the event cannot be said to have taken place. And yet, based on his vague memories of his uncle, and the fact that no one in the family can say where he lives or whether he is living at all, Ollie is already convinced that: 1. His uncle is alive and 2. His uncle did something to Ollie that has bearing on why Ollie cannot know himself. He feels he knows these points inherently, what one would call faith.

Throughout the novel Ollie is in a state of questioning, seeking to illuminate truth even as he obscures it from those around him. “Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes the truth. Repeat a memory, whether or not the memory is flawed, and the same thing happens.” Ollie’s reaction to Mary’s student mirrors his own, inner interrogations of his imperfect memory; his defensiveness actually having to do with the possibility that he was himself a victim of abuse. “Do I doubt Sylvia’s story because I’m uncertain about what happened to me? Am I a victim? Or have I imagined it? If it happened, why didn’t I tell someone?” Implied but not overtly explored is the question of the gender divide in terms of sexual abuse; perhaps Ollie feels there is more shame in being a man and having been abused by a male member of his family, than there is in a male-female date rape scenario.

In the last third of the novel, Ollie convinces Mary to move abroad for a couples’ adventure, his secret agenda being, of course, to track down Uncle Scotty. After awkward family engagements, travel gaffes, and a few truly lucky breaks, Ollie’s journey comes to a peak. And while the story lands safely, I can’t help but acknowledge lingering resentment for the very character I also rooted for. Ollie’s complexity is at once overstated (by himself), and also understated by his oafish actions. I was often frustrated with Mary, the put-upon girlfriend who attempts to reclaim the power imbalance with soapy manipulation tactics. Ollie’s highly serendipitous dalliances with other women on his travels, exotic beauties that appeared solely to comfort and assist him in his not-quite-Homerian quest, felt so fantastical and idealized as to suggest that he is merging with his literary alter-ego, becoming more Oliver than Ollie.

Garstang’s dry humor and tight, aphoristic writing make for an engaging, unstoppable read. The Philosophy classroom discussions frame and inform the narrative, and provide context for Ollie’s actions. The author’s close attention to structure and tone support the reader’s emotional journey, and enables him to balance the richness of Ollie’s interior monologues with those facepalm dialogues. Ollie’s eventual discovery of the truth arrives padded with tenderness, yet the impact resounds. We are not so much left with questions as we are rewarded for the search. Oliver’s Travels was indeed transporting, challenging, and provocative, drawing me in as the mystery unfolded.

A Conversation with Peter Ramos about His Book of Poetry, Lord Baltimore

I grew up in the wake of the Vietnam War (I was 6 when the U.S. left Saigon), and I would see images of that war on TV as a young child; my earliest memories, which go back almost to language acquisition, are of the televised moon landing (a few years after it happened), hippies, the [relatively recent at the time] deaths of the Kennedys.

Editor’s Note: Peter Ramos and Paul Nemser each have published books of poetry this year. Their conversation about those books is presented here in two linked posts. In this post, Paul Nemser interviews Peter Ramos about Peter’s book, Lord Baltimore. Peter Ramos’s interview of Paul Nemser about Paul’s book A Thousand Curves ca be accessed here.

Peter Ramos’ poems have appeared in New World Writing, Colorado Review, Puerto del Sol, Painted Bride Quarterly, Verse, Indiana Review, Mississippi Review (online), elimae, Mandorla and other journals. Nominated several times for a Pushcart Prize, Peter is the author of one book of poetry, Please Do Not Feed the Ghost (BlazeVox Books, 2008) and three shorter collections. Lord Baltimore (2021), his latest book-length collection of poems, was published by Ravenna Press. He is also the author of one book of literary criticism, Poetic Encounters in the Americas: Remarkable Bridge (Routledge, 2019). An associate professor of English at Buffalo State College, Peter teaches courses in nineteenth- and twentieth-century American literature.

*

Nemser: So many of your poems in Lord Baltimore are about night—for example, “Night Shift,” “ Night Gown” “Night Flight. What does night mean to you?

Ramos: Thanks for these questions, Paul. I’m happy to be doing this with you.

I’m not sure this answer will make the poems you mention any clearer, but I have long had two strong feelings about night—fear and excitement. My son is now 12, almost 13, and when I was his age, I was terrified of being awake when everyone else was asleep. But in the summer of my 14th year, I turned to reading in bed, late into the night, and that solved my fear of not being able to get to sleep with everyone else. In my mid-teens, and when I could drive, I would go out with my neighborhood friends to punk and new wave clubs in the city (Baltimore), though I lived with my family in the suburbs. That time (during my 11th and 12th grades) and those first experiences of city night-life were filled with great excitement, thrilling with new, original (to me) experiences. But I have also felt fear of the evening throughout my life. I think I turned to drinking in part because of such fear. There have also been times where I was clear-headed, present and at ease in my skin when night came on, and I felt a different kind of excitement.

Nemser: “Night Shift” is about seeing and working, sleeping and waking. Night comes, “truer than time,” with its own distances, its own light:

All day it was summer, an open melon

thrumming with insects and minutes.

Now something else jumps

bolt upright, awake. Moonlight roams

for a thousand miles.

Is “Night Shift,” in part, an ars poetica?

Ramos: Yes, I can see that, and as I implied above, it’s also tied up with my personal relationships to night, especially my sober, clear-headed ones.

Nemser: Night Gown” is unusual in your book as a poem in the third person. Why did you use the third person? You have an epigraph from Emmanuel Levinas who saw the origin of ethics in a person’s encounters with the “face” of the unknowable “Other. Levinas said, “The beyond from which a face comes is in the third person." How did you become interested in Levinas?

Ramos: I wrote that poem long before I knew about Levinas. I use Levinas in my book of academic criticism, Poetic Encounters in the Americas: Remarkable Bridge (Routledge 2019), as a lens through which to view the translation of poetry. In this poem, I saw a connection with his passage about waking up as a way of actively and responsibly making the world come to life (as opposed to not waking by hitting the snooze button, say, and thereby continuing to let the world cease to exist). The poem, for me, is thereby like his discussion of the relationship of the self to the Other, which we decide to make before reason yet out of obligation. This, too, seems like a responsible way to make the world come to life. I think I used the third person because it seemed to me like an experience that many share, one not limited to me.

Nemser: “Night Flight” closes your book with what might be a first-person experience of the Other. The Other, according to Levinas, is “infinitely transcendent, infinitely foreign.” In your poem, the speaker wakes at night saying, “Do it,/ that thing, again. He goes up into the attic and encounters “a Syrofoam/ head, anonymous/ wig-stand. I knew it…. The thought of this anonymous face “prickle[s] [him],” and he thinks of a street that runs “forever. You end with these lines: “I took/ that manikin head—/ frightening white// center of all things—/ for a sign, I took/ the matter as closed. Please talk about “Night Flight. What is the “flight”? What is the sign? Is the manikin really the Other or a mock-up? What are the matters that are closed?

Ramos: I’m not sure this will satisfactorily answer your questions. Like “Night Shift,” this poem runs ahead of me, in terms of its own logic, its atmospheric, uncanny plot. And I like that. I don’t want to know, completely, what my poems are about. To me, this poem seems to have its own understanding of time, an unconventional, dream-like presentation of it. I think there’s a hint that the flight is in the present moment, away from such a sense that the matter was closed. What does/ did the speaker take as closed, you ask. I think a sense that at the center of his world (especially since childhood) lies an enticing, alluring but ominous, even terrifying, and controlling fate-like power or entity. I wouldn’t call it the Other. I guess it’s fate, in the sense that I take Emerson to mean it in his essay with the title of the same term. I hope the speaker can activate more autonomy over his life.

Nemser: Themes from “Night Shift” are explored throughout your book. “Con La Mosca” describes the experience of waking suddenly and alone in a hotel in Frascati, not far from Rome. There’s a mix of dream and half-awake excitement. A stream of short, enjambed couplets, the poem flows through a current of history and free association, but events are described as if they happened almost at once. Aristocrats play “homo-erotic footsie” in marble fountains. In the hotel bar they drink to the death of Il Duce. In the ballrooms, women wear trappings of Eros—expensive heels, powdered cleavage, puckered lips. Outside there’s celebration, “corks/ & machine guns/popping off. All of this flow seems to be powered by Sambuca with a few coffee beans—a drink known as “With the fly,” “Con La Mosca. The poem ends with music, the speaker calling out a gentle crescendo as if he were a composer: “Piano,/ piano, mezzo-/ forte. How much of this poem is memory, how much history, how much imagination?

Ramos: I think your questions at the end work well—parts personal memory (I stayed in such a hotel once), history, and imagination. Like “Night Flight,” this poem to me presents a kind of haunting, a scratching of some invisible unreasonable itch. To me the speaker seems possessed for an intense moment, as you put it nicely, by “a current of history and free association, [by] events [that] are described as if they happened almost at once.”

Nemser: Your poems have many different ways of presenting time. In a number of short, present-tense, prose memoirs, you often describe events that proved indelible. These poems are full of period detail from the 1960’s or 1970’s. Many depict generational conflicts or erotic encounters. Could you tell us more about the inspiration for these poems?

Ramos: Yes, but I’m a bit uncomfortable with the term “memoirs” as a descriptor for these.

Nemser:

a. “Can’t Get There From Here” is a narrative of a teenage garage band denied access to their gig at a fair because of how they look—in an old car, in “black suits and ties, hair gelled up tall. They came to be cool, but are shunted from entrance to entrance till the car gets “hot as hell. Our eyeliner stings.

Ramos: In terms of pop-culture or period detail, this poem seems connected to the early 1980s. The poem is probably more autobiographical than others in that I was in a band in my mid-teens to early 20s and we grew up near a rural part of Maryland. I can identify with the speaker’s desire to fit into a sense of his home or place even as he clearly also wishes to register his defiance of its provincialisms. But in the poem, such defiance is also lambasted for its pretentiousness and innocence.

Nemser:

b. “Immigrant Song,” is about a musical war between the speaker and his father. Son puts on high-volume Led Zeppelin in his bedroom. Father is in his own bedroom, daydreaming back to his old life in Venezuela, but the noise from the son is too much. Father slams the door and turns on the Four Tops. Then in a moment of magic, a deeper past comes alive in the remembered time of the poem, the father’s father beating a tango rhythm on his coffin wall. For generations, the men in the family have used music to “stage our frustrated coups. What else can we do? We are not kings. These have been themes for men from time immemorial: battles between fathers and sons, old and new; the immigrant’s life—being from elsewhere but living in a strange land; how the dead speak to us and through us. Do you see your poetry as part of a musical lineage that allows you to know and overthrow the past?

Ramos: I don’t think the speakers can overthrow or escape their pasts in this poem. The father in the poem is transported to his own bedroom from the 1940s and then early ‘50s, and he enacts the same kind of Oedipal revolt as his son with his own father, and so on down the patrilineal line. The older I get the less I seem to know about my poetry. In my limited experience, I feel more calm, less antagonistic in my early 50s. My father was not violent, and he never taught me to fight, so this seemed like the closest thing to the father-son agon that I could use.

Nemser:

c. “Master Bedroom” turns these memoirs on their heads. It’s a present-tense, stanza-ed narrative of hallucination in the 1960’s. “A cleaned-up country sleeps beneath Sputnik and all the crown molding. The house has iconic features of what realtors now call “a mid-century gem”—constructed for soldiers who returned from WWII and started families. The married couple in the poem, however, live in a sci-fi horror movie combining paranoia, government experimentation, and wild sex. Characters appear and vanish as if in a masque. A field mouse in the heating ducts, crew-cutted scientists in the basement working on hallucinogenic truth serum, the couple’s grandparents, the women speeding on Dexatrim.

Ramos: Much of this poem is a meditation on the houses, fighter jets, drugs and pop-culture of that period. I grew up in the wake of the Vietnam War (I was 6 when the U.S. left Saigon), and I would see images of that war on TV as a young child; my earliest memories, which go back almost to language acquisition, are of the televised moon landing (a few years after it happened), hippies, the deaths of the Kennedys (Robert the year before I was born; John F. fresh enough that it was still in the air). As is hopefully clear, my father was an immigrant, but my mother’s family goes back generations in this country, and her father, grandfather and brother were all in the U.S. Navy, so my brother and I received all these forms of mid-century U.S. culture and institutions early. We grew up about 40 minutes from Washington, D.C., and our family frequently visited the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum when my brother and I were young. I don’t know why these things have such a strong hold on my psyche. Like poetry, they linger, deeply familiar but a little out of focus; they continue to haunt me. I think Rilke mentions in his Letters to a Young Poet that we spend much of our adult lives trying to distill and understand our earliest memories.

Nemser: Some of your poems are like paintings of a past that still exists in the present. “Hawaiian Tropic,” for example, is a portrait of desire, sensual and sensuous in its detail, perhaps tracing the path of the speaker’s eyes and mind as they glide over beautiful women lounging by a pool. “God did I lean/ toward them—and still do—. You emphasize these movements with changing line lengths and with line breaks.

Ramos: I like your description above: “Some of your poems are like paintings of a past that still exists in the present.” I don’t have much more to say about this poem.

Nemser: Lord Baltimore is the title of both your book and its longest poem. The title has several, mainly ironic resonances; for example, the poem conjures up the English noblemen who founded the Maryland Colony, the city of Baltimore—depicted as a rough, industrial, down-and-out, dead-end place—and the poem’s struggling speaker, who is focused on memories of one hot, “wretched,” Twentieth Century, bohemian summer in the city. Who and what is Lord Baltimore?

Ramos: For me, Lord Baltimore is the city, itself, a character in the poem, alluring, brutal, demystifying, or maybe experience, itself, which can rob us of our ideals. I just thought of Emerson’s essay of the same name (“Experience”). And in some ways, maybe the speaker sees himself as Lord Baltimore, but ironically, as you imply, cynically—a clownish drunken failure who bitterly mocks himself.

Nemser: Your long poem begins with an italicized epigraph introducing the city and the life of the speaker within it. When did you write the epigraph in relation to the rest of the poem? The epigraph made me think of the beginning of La Boheme, where the young artists in a garret in Paris in the winter are burning their books to keep warm. In “Lord Baltimore,” young artists swelter in broken-down studios with bad plumbing, bad furniture, kitchen cabinets that “pulse all night with bugs. But there’s a breeze through an open window, and a view: “The rusted, industrial blocks of Baltimore” are “all smoke and unloading, 9 to 5,” and by dusk the lights come on with an eerie, inanimate beauty. The artists indulge in “high talk, inspired. They believe their whole lives will be art and poetry. Then they realize that everything is crumbling. By day they taste the dust of idealism, and by night they have “a gathering unbearable thirst. What influences were you thinking about when you worked on “Lord Baltimore”? What is the relationship in the poem among dissolution, disillusion, craving, and beauty?

Ramos: “Lord Baltimore,” as is clear in the book, is a longer sequence poem. I had written a long sequence poem a few years earlier which appears in my first full-length collection, Please Do Not Feed the Ghost (BlazeVOX Books 2008), a poem called “Watching Late-Night Hitchcock.” I wrote the italicized epigraph in this collection, as well as a few others, earlier as individual poems. For me, the epigraph happens earlier in the speaker’s life and foreshadows what will come.

I’m not sure I can identify the influences for that poem. I’m sorry. I wish I could. I think all of the terms you use are present in the poem. I hope I wrote myself out of that poem. It was painful to live some of it, and it was difficult to write it.

Nemser: After the epigraph, the body of “Lord Baltimore” begins with an ironic line that has the feel of epic quest: “Here begins the journey to bread. You launch into a description of hellish jobs done in the toxic heat of that Baltimore summer. It reminded me of summer jobs I had in my teens—janitor in a crematorium, washing down the walls of an airless, ten-storey staircase in a newspaper plant, scouring huge I-beams in vats of hydrochloric acid and boiling lye at a plating company. Later, when I read about journeys to hell or knights crossing a wasteland, those jobs would come back to me—the stink and sweat and the sense of unreality. Is there an element of spiritual journey in “Lord Baltimore”?

Ramos: I think so. I think the following section alludes to a kind of spiritual journey:

I got out.

Walked for years, the flames

eating my skin

less and less, dumb and dazed,

afraid but steadying, toward no place

I’d ever known.

Nemser: In your section “Wisdom Teeth.” a grueling time with family and work and drinking merges into the surgeon’s gruesome extraction of in-grown teeth. The speaker woke up in a Percocet daze in an air-conditioned room belonging to a girlfriend’s parents, and now he asks, “Why go there now, why hold on to those bloody molars, your ingrown and bone-aching twenty-something teeth?” What do those teeth represent in your poem?

Ramos: I think that, as with the rest of the poem, the speaker feels compelled (for some reason) to go back to that period of his life, despite or even because it was painful. To me, there’s a desire to hang on to it and a self-command to let it go, the latter the healthier option but maybe requiring the former first.

Nemser: Your book often refers to music. The long poem uses lines from the Neil/ Nilsson song, “Everybody’s Talking At Me. The singer feels blind and deaf to the people around him—“I don’t hear a word they’re saying. “I can’t see their faces. He seems alien, out of place, dislocated, but he dreams of finding his place. It’s an escape into weather, into turbulence, and a mastery of them. “I’m going where the Sun keeps shining through the pouring rain. He’ll be riding winds and “skipping over the ocean like a stone. Many of the poems in your book Lord Baltimore begin with alienation, displacement, dislocation. How do the poems drive toward a place like the one where the song-singer longs to go?

Ramos: I always associated Baltimore, and especially my life in my 20s in that city, with the film, Midnight Cowboy, and that song recurs throughout the movie. The “green” cowboy goes to a huge, alienating city and loses his innocence (not that I think of myself as a cowboy). It’s such a devastating and beautiful movie, and to me, the song sounds very much like something a junkie would fantasize about, a longing to escape through his powerful pain medicine (I think I once heard Harry Dean Stanton say the song was about heroin). I’ve never done that drug, thank God. But the sense of womb-like comfort and escape seems like (to me) what the speaker is longing for throughout that poem. Does he get there? The poet isn’t there yet, but he hopes to.

Nemser: The final section of “Lord Baltimore” zeroes in on “the only thing/ you remember now” from all the drinking. Hung over, the speaker went out, and the street was lined with people evicted from their apartments. “By their own cheap sofas, gold shoes and negligee, spilled boxes of glass jewelry in the gutter—the Call-Girls,/transvestites, tall and elegant still but without their wigs, in ratty bathrobes/ out without time to put on makeup, suddenly/forced to wander the streets in broken pumps—/a few in slippers—breasting the cold bright/ morning, all of them, moving on/chin-high and stiff-lipped. This is the image that stays with the speaker—a community of people cast-out, performers only partially costumed, neither who they were, nor who they were not, but “tall and elegant still. What do these people mean to you?

Ramos: To me, they are the strongest, bravest people in the book. As such, the speaker simply cannot understand them. How did they do it, he asks, amid such desolation, loss, humiliation, poverty. I think the speaker wishes he had that kind of courage and fortitude.

A Conversation with Paul Nemser about His Book of Poetry, A Thousand Curves

As I’ve grown older, I’ve felt that I know less and less about the world. The fragility of the present and even the past adds to my sense of the fragility of the future. It can go in every imaginable and unimaginable direction—in a line, in a circle, in curves. And when a rain that had never rained begins to rain, it could bring pain and death or beauty and delight.

Editor’s Note: Paul Nemser and Peter Ramos each have published books of poetry this year. Their conversation about those books is presented here in two linked posts. In this post, Peter Ramos interviews Paul Nemser about Paul’s book A Thousand Curves. Paul Nemser’s interview of Peter Ramos about Peter’s book Lord Baltimore. can be accessed here.

Paul Nemser’s third book of poetry, A Thousand Curves, won the Editor’s Choice Award from Red Mountain Press and appeared this past April. It is a collection from a lifetime of writing poems. He grew up in Portland, Oregon where he fell in love with poetry while reading in the storage room in back of his family’s tool store. He studied poetry with Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, Stanley Kunitz, and many others. His book Taurus (2013) won the New American Poetry Prize. A chapbook, Tales of the Tetragrammaton, appeared from Mayapple Press in 2014. His poems appear widely in magazines. He lives with his wife Rebecca in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Harborside, Maine.

*

Paul Nemser: Peter, I enjoyed answering your questions!

Peter Ramos: Let me say that I, too, enjoyed this exchange, both asking and answering questions.

I see that you studied at Harvard with Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop. I’d love to hear more about that. They’ve been impressive to me since I first started writing more seriously back in college. I have a funny story about Lowell.

Nemser:

Robert Lowell

I had a writing seminar with him in 1968 in my sophomore year of college. There were 10 or 15 people in the class, mainly undergraduates (e.g., Heather McHugh, James Atlas, Robert B. Shaw), with graduates such as Frank Bidart and Lloyd Schwartz often present. I wish I had taken more notes and could remember those days more clearly.

Lowell came to class quite regularly and was on time. Though he usually wore typical Harvard professor clothes, I noticed one or two times that he was wearing what seemed to be bedroom slippers. He sat at one end of the seminar table and began talking in a soft drawl. The class hung on his every word. He was seen as the great American poet of the time.

Lowell had a large head. He tucked his chin into his collar and looked down as he spoke or looked out over his glasses. He came into class, it seemed, with a plan of what he was going to discuss. He might read poems of other poets and talk about them and about history, he might talk about writing. Then he would devote the bulk of class to student work. I found his comments to be elliptical, expressed in his personal diction, hardly ever including specific editorial suggestions. He praised things he liked and was not unkind about things he didn’t like. Lowell allowed a fair amount of student discussion in the class.

Lowell taught me to embrace the idea of poems written in rough form—forms that might seem unpolished or full of conflict. It was Lowell who first introduced me to early English Renaissance poets such as Wyatt and Raleigh and who led me to study Donne’s language and form. He also talked about writing drafts in strict form, then cutting them back to tighten them, freshen them, give lines an explosive force. Another point that stuck with me was Lowell’s remark about ambition. He said that many people can be good poets; only a few can be great poets; but you can’t be a great poet unless you try. For better and worse, this encouraged me to take bigger risks in my poems and take on hard, perhaps unattainable goals.

Elizabeth Bishop

I took Bishop’s poetry writing seminar at Harvard while doing graduate work in 1975. The seminar included both undergraduates and grad students. In 1975, I had read and admired her poems, and I had heard a lot about her, so I was eager to meet her. In class, she seemed very restrained—in her dress and appearance, her polite manner, her punctuality, her unassuming ways of talking, and the conscientious precision of her words. She kept to herself. I didn’t get the sense that she enjoyed connecting with students. She warmed more, and seemed pleased, when talking about animals.

Her writing was so strong and flowed so naturally. Her poems were models of how to observe the world closely and to write well from the beginning of the poem to the end. She conveyed this by assignments that sometimes involved a particular form, but also could be to imitate or answer another poem or to write about something specific or in a defined voice. Her comments on our poems and her fuller comments on poets she admired got across that poetry could emerge from care, precision, honesty, and really attending to what was there.

In the early 2000’s, after a work trip to Rio de Janeiro, I wanted to see Samambaia—“fern”—where Bishop had lived with Lota de Macedo Soares in the mountains near Petrópolis. But when I arrived, the front gate was locked, and there was no one to let me in.

I’d like to hear your story about Lowell.

Ramos: I had a psychiatrist in Baltimore back in the 1990s, and he told me he was an intern at Bowditch Hall (in McLean Hospital near Boston) and this wild-eyed guy with tousled gray hair named Robert Lowell was admitted. Apparently, Lowell was telling everyone that he wanted to speak with the president. No one believed him (not surprising—the patients there made such requests all the time). Somehow someone relented and gave him the phone. He immediately dialed the White House and spoke with John Kennedy and Jacqueline, whom he knew, of course. I asked my psychiatrist what the doctors did after that. He told me they revoked his phone privileges.

I can picture the whole thing, though I never met him. I’m envious that you got to study with such famous, great poets.

Ramos: A Thousand Curves seems neatly divided into a number of themes or topics: a section with a speaker who is growing old and still very much in love with his partner; a section that seems to deal with a speaker’s relationship to his (I’m just going to assume that the speaker in many of these poems is a man, but there are exceptions) Ashkenazic family going back through generations (another assumption, and please correct me if I’m wrong); a speaker traveling and/or entering foreign lands, etc. Given these clear distinctions, it’s tempting to think you wrote these poems with themes in mind, but I’m also stunned by your original and powerful images, phrases and language—“Tree wings furl upward higher than birds” (from “Current”); “Chitters drown the radio jazz” (from “Song Over Song for My Father”); “Wasps fly at our teeth but miss and freak the screen” (from “End of the Century”); I could go on and on—which makes me think the poems began with these (images, phrases, language). I want to ask, did you write them from an idea that you then developed, or did you write them from the inside out?

Nemser: Almost always inside out. Usually, I just start writing and see where the poem leads. A poem might launch from anything or anywhere—experience, memory, dream, something I’ve read, a film, a song, something I’m thinking about, often something I can’t explain. As a result, editing is equal parts tightening, heightening, cleaning, but also letting the subject reveal itself. This can take years. All that said, life generates topics. I’ve been married to one woman for 47 years, so I frequently write about her and our connection over time. Also, some poems begin in response to other poems of mine, and if the response works, I may be on the road to a theme.

You’re right that I’m from an Ashkenazic Jewish family—from Russia (now Ukraine) on my mother’s side and from Poland and Lithuania on my father’s. My grandmother often talked about her life in Chernobyl. They left in 1913. My parents were born in the US, and my maternal grandparents, my parents, and I lived near each other in Portland, Oregon.

Ramos: I’m impressed by the way the poems in your collection travel through time and allude to ancient or elemental or enduring things—seas, the moon, love, the natural word, as well as Aubades—and things more current and/or part of American pop culture—popular bands and songs from the last 4 or 5 decades, including songs and albums from The Ramones, U2, as well as jazz tunes. I guess that’s less of a question and more of a statement. I’m a musician, and I’m interested in your relationship (in your life and in your poems) with music.

Nemser: Those ancient things are still here, still marvelous, sometimes in reach. So it’s no surprise that seas, the moon, love, nature, and waking in the morning show up in pop music and jazz—in every kind of music. I love music. No one in my extended family had voice training, but everybody liked to sing, the older people in Yiddish. I remember listening to Burl Ives when I was quite small. At five or six, I started listening to rock and roll, especially Little Richard and Elvis, and then doo wop. My parents listened mainly to standards—Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, Tony Bennett, and on TV, Perry Como, Dinah Shore. And they loved Broadway show tunes. I played violin for about ten years—classical music and Yiddish songs. I quit early in college. My girlfriend in college and graduate school was a violist who taught me a lot about classical music. My wife loves “early music,” especially Baroque opera. My son sends me to great music—usually popular music—that I didn’t know about before.

My musical tastes have always been eclectic, but here are examples: Bob Dylan, Leadbelly, Mississippi John Hurt, Child Ballads, Hank Williams, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Yiddish songs my grandparents sang, surf music, soul music, Chicago blues, British invasion, Leonard Cohen, Donna Summer, The Clash, U2, Buena Vista Social Club, Prince, J. Balvin. In the 1960’s, my father listened to a few Bossa Nova records over and over. Decades later, working in Brazil, I fell head over heels for classic samba, Bossa Nova, Tropicália, forró—and more.

Many of my poems were written while music was playing. I love song lyrics. Songwriters can be poets, and poets songwriters. The Child Ballads are written-down songs. Blake and Wordsworth and Coleridge (among many others) wrote with song in mind. Brecht wrote songs that Weill put to music. Vinicius de Moraes who wrote the words to “The Girl From Ipanema,” was a poet who wrote and sang his own songs. And then there’s Bob Dylan.

Ramos: As I wrote, you name the poets you worked with in your bio., but I’m also interested in other poetic influences. I detect some Paul Celan, especially in the Germany poems like “Letter from Berlin”: “All April first I’ve dreamt and redreamt/ that everyone’s feet are asleep.” Are you willing to cite others?

Nemser: I first read Celan in college years, and he’s been a significant influence since then, though he’s inimitable. The Bible has been a constant influence because I read it often. Beyond that, here’s an incomplete list: Homer, Greek tragedy, Sappho, Catullus; ancient Chinese poetry; Hafez; Dante; Shakespeare; Renaissance ballads and early Renaissance sonnets; Spenser, Marlowe, Donne, Marvell, Milton; Goethe, Schiller, Büchner: Edo period poetry in Japan; Ghalib; Blake and all the other Romantics; Dickinson; Whitman; Mandelstam, Pasternak, Tsvetaeva, Akhmatova; Lorca, Borges, Neruda, Vallejo, Drummond; Yeats, Eliot; Langston Hughes, Ted Hughes; Brecht, Ginsberg, Amichai, Heaney, Walcott, Milosz, Hayden, Rich, Zbigniew Herbert, Clifton, Szymborska. I’ve left out a lot; notably my teachers and my friends, who have been a huge influence on me. And I admire many many poets writing now whose work gets into my head, my heart, and my poems.

Ramos: I see your collection’s title appears in a poem called “Mil Cumbres.” Did you have in mind other explanations for this title, more metaphoric ones? I read it this way, especially given the way the poems in your collection cycle through separate but related topics and then curve around, toward the end, to the speaker and his beloved who continue to grow, spiritually and in love.

Nemser: Yes, I intended the title metaphorically. We have to deal with all kinds of curves. Often the curve brings a surprise. You think you’re going one direction, and suddenly you’re going another. There are the steeps and hairpins and revelations of a road like California Route 1. Who knows what’s coming or who’s going “around the bend”? The batter expects a fastball, the pitcher throws him a slow curve.

Curves are also pleasurable. We like to look at them, to run hands over them, to touch the curves in a beloved face. The natural world is made of curves—genes, flower petals, rolling hills, river bends. And, as you suggest, curves can return you to where you started.

Ramos: I really enjoy the way the future seems terrifying, hopeful, uncertain, and potentially dangerous in your poems. In “The Origin of Yet,” the speaker notes, “For moments/ we’re out of danger, afraid of nothing—when/ a rain that had never rained begins to rain.” Yet in other poems, there’s a promise of delight yet to come. Your poem, “Aubade,” ends with this lovely image of dawn: “Dockworkers pull the morning moon up by her arms/ to watch her slither on carts, or dive to sea and swim away.” Is this also related to the uncertainty of what is to come that your title seems to connote? In fact, I’d be interested in any of your thoughts on the way the future presents itself in your poems.

Nemser: As I’ve grown older, I’ve felt that I know less and less about the world. The fragility of the present and even the past adds to my sense of the fragility of the future. It can go in every imaginable and unimaginable direction—in a line, in a circle, in curves. And when a rain that had never rained begins to rain, it could bring pain and death or beauty and delight. As I suggest in “Felicidade,” we could end up on “a small, unspeakable/ shoal of chances of drowning// in joy.”

I do believe in mathematical and scientific truth, and in the ability of math and science to say useful things about the future. In fifth grade, I read a book about wonders of math, which had a picture of Pascal’s triangle. I’ve been thinking about probabilities ever since. As a lawyer, for example, I know that evaluating likelihood becomes a habit of mind. Weighing evidence and assessing credibility are all about likelihood, and many legal issues entail prediction. I suspect that these habits of mind influence my poems and what they say about the future.

Ramos: Your “In the Alley of Perpetual Industry” nicely combines elements of the sacred and profane

Our lips and eyelids burn away,

leaving all we crack open for holy,

all we mistake for decay.”

I always associate such combinations with T. S. Eliot and Ginsberg’s “Howl.” Are there other poets you are influenced by who make such combinations?

Nemser: By the 1970’s, I was deep under the influence of Neruda. His essay “Toward an Impure Poetry” made a big impression: “Let that be the poetry we search for: worn with the hand's obligations, as by acids, steeped in sweat and in smoke, smelling of the lilies and urine, spattered diversely by the trades that we live by, inside the law or beyond it. A poetry impure as the clothing we wear, or our bodies, soup-stained, soiled with our shameful behavior, our wrinkles and vigils and dreams, observations and prophecies, declarations of loathing and love, idylls and beasts, the shocks of encounter, political loyalties, denials and doubts, affirmations and taxes.” My poem “In the Alley of Perpetual Industry” seeks this kind of impurity.

Mixture of sacred and profane is in much of the literature I love. Once when I reread The Iliad, I was also going to action films like “The Terminator.” The carnage in both was immense, unthinkable, yet The Iliad explored dimensions of the sacred that the action films never dreamed of. The Inferno also is a mix; for example, the predatory scenes of falsifiers and betrayers near the center of Hell might fit in a horror movie, but The Divine Comedy is undeniably an evocation of the sacred. The profane and sacred appear together in everything from Shakespeare to Goethe’s Faust to Kafka to García Márquez.

Ramos: I’m ashamed that I have never written a good love poem, but you have many in this collection, poems that present an enviable partnership between a couple that enjoy ever-increasing love over the years. Have such poems come easily (as if poems come easily!) or have you had to learn how to write love poems.

Nemser: I first wrote love poems around the time I married my wife in 1974. We’ve always had a lot to talk about, so our love has always been involved with language, and it has evolved with language. We’re both only children, and our son is an only child. It’s a tiny family, and we look to each other. There are hard times and happier times. Both can generate poems. Poems about love are no harder or easier than my other writing, but given how my life has gone, writing love poems has been inevitable.

Ramos: These are poems of beginnings and endings, mornings, evenings, and travels that lead the speaker back to a beginning: “Here I am” (from “What I knew and What I Had to say”), or “There was no way down” (from “Mil Cumbres,” as if one cannot return from such a height without being changed, as if the truly new transforms us, the old way hidden forever): or, “the squawk circles back like a crack in vinyl” (from “Field Guide to Mercy”); or “the god of endings hangs on his hinges” from “Janus”). Are these departures and arrivals themes you have consciously meditated on in your poems, here and in the previous collections?

Nemser: I am interested in beginnings and endings. I don’t remember not being interested in them. And I’m interested in appearances, vanishings, recurrences, periodicity. I don’t consciously meditate on arrival and departure themes in my poems. My mind just goes there, as it goes to themes of transformation. I feel all those themes in my body as it ages, and I’m attracted to writings about those themes: e.g., Genesis, the Book of Job, Lao Tzu, Heraclitus.

My two earlier books do explore similar themes, but both are crazy, myth-influenced narratives. Taurus is a wild retelling of the Europa story: A bull-gargoyle in St. Petersburg, Russia is possessed by a god, comes down off of his building, roams and works in the city, and falls in love with a mysterious woman named Europa. In Tales of the Tetragrammaton, set in Portland, Oregon from the 1950’s to the 1980’s, a woman whose life resembles my mother’s is visited constantly and bewilderingly by the unpronounceable name of God.

Ramos: I’m so impressed by the unobtrusive rhyme and poetic forms you employ in many of these poems. Is there a moment in the composition of your poems when you decide to use such forms?

Nemser: Thanks. It all depends on whether I am trying to write in a strict, traditional form—e.g., with meter and end-rhyme or with required repetition. If so, I have to make that decision at the beginning and then try to stick to the rules, nearly all of which I first learned from Robert Fitzgerald’s wonderful prosody class in college. If I’m not writing in a strict traditional form, the effects just happen, usually by process of discovery in the editing.

Ramos: In your poems that allude to Japan, do you feel like you’re channeling or speaking back to Basho and others? I’m particularly fond of “May” and “Garden with No Boundaries.”

Nemser: Yes, I first read Bashō when my high school sold little haiku books in a bookstore in an alcove between classrooms. I read Narrow Road to the Deep North and other of Bashō ‘s haibuns when I was in college. In those years I also realized that the landscapes around Portland, Oregon and landscapes in Japanese poems and woodblock prints had strong similarities—fogs, torrents, fish, frogs, big solitary mountains, bridges, blue-gray seas.

My poem “Garden With No Boundaries” is a response both to Bashō and to Musō Soseki, the 13th Century poet, calligrapher and Zen monk who was the foremost garden designer of his time. While in Kyoto, I got to visit the Zen temple called Tenryūji, of which Musō Soseki was the first abbot and also the designer of the magnificent garden discussed in my poem. It was a joy to see how harmoniously the garden’s plantings, trees and water related to the temple, the mountains, and the famous bamboo forest not far away. Only later did I learn that the animating spirit of this place was Musō Soseki, whose poems, translated by Merwin, had long been on my bookshelves. The signs at Tenryūji had called him Musō Kokushi, another of his names.

Ramos: Does your location, i.e where you happen to be living, strongly affect your poems? I understand you live in two different places, depending on the season, I imagine.

Nemser: The particular landscape and atmosphere of a place enter the images in my poems and often take them over. Oregon, where I grew up, became imprinted on my brain when I was small, and it emerges when I write about childhood. My wife and I have gone to Maine for 47 years—first on our honeymoon—and it’s a beautiful, sometimes bleak, place with amazing views—ocean, forests, fast-changing weather, encounters with animals. Love, life and death reside there. Many of the poems in A Thousand Curves are set in Maine. Finally, I’m excited by travel. It’s about the unexpected. Wandering in a foreign place, trying to speak the language, jolts me out of the world I’ve known. I feel a new propulsion—I see, feel, remember more. Some experiences are written in fire.

Connecting Through Chinese Cookery: A Conversation with James Beard-nominated author Carolyn Phillips

I hope to not only encourage people to remember the foods and to cook them, but also to appreciate them. You can have a great chef, but chefs need to have a clientele with sophisticated understandings of what is being served to them.

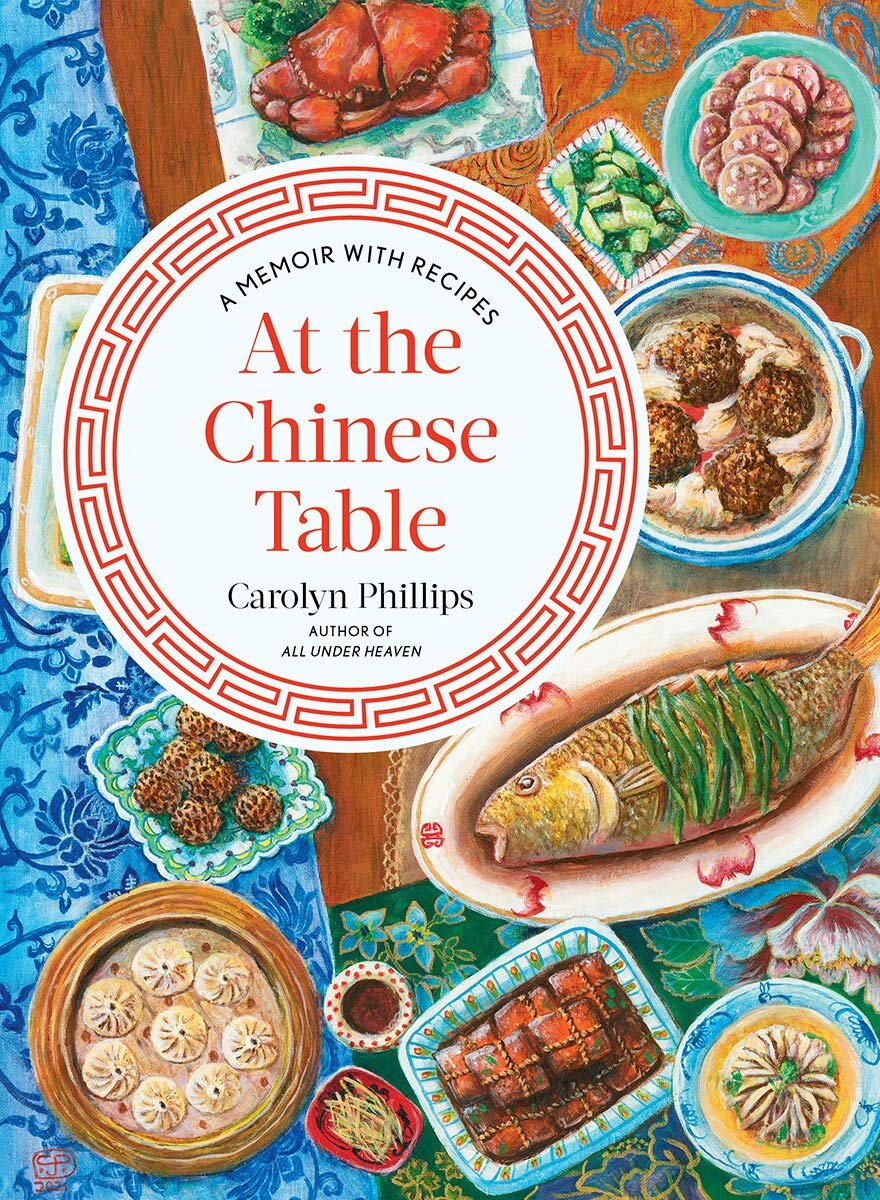

Forty years after she moved to Taiwan, Carolyn Phillips’s first book, All Under Heaven, was a finalist for the James Beard Foundation’s International Cookbook Award and her second book, The Dim Sum Field Guide: A Taxonomy of Dumplings, Buns, Meats, Sweets, and Other Specialties of the Chinese Teahouse, also came out that year. Drawn to her background and the story of her cross-cultural marriage to author and epicurean J.H. Huang, which she discusses in her latest book, At the Chinese Table: A Memoir with Recipes, I recently sat down to speak with Phillips over Zoom.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: When you first landed in Taipei in 1976, Taiwan was at a crossroads. Longtime leader Chiang Kai-shek had just passed away a year earlier and across the Taiwan Strait, the decade-long Cultural Revolution came to a close as Chiang’s nemesis, Mao Zedong, also died. When you got to Taiwan, what did you know about the politics of the region and did you understand what a pivotal time it was?

Carolyn Phillips: I was an oblivious kid. I was just out of college and had no idea what I was doing. I didn't even know why I was really there. I wanted to learn Chinese, but I didn't know what to do with my life. I was like a headless fly with no sense of direction, as my mother-in-law used to say. So, no, I really didn't understand anything and was slowly figuring out what the world was about.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: This was at a time when the United States was in the Equal Rights Amendment era and women were no longer expected to marry, have kids, and stay home right after finishing school. What was your biggest surprise in Taiwan when it came to women's equality? Certainly your mother-in-law was very strong and you learned a lot about the women in J.H.’s family, but was there something else that showed we are all much more alike than we are different?

Carolyn Phillips: At that time it was at the very tail end of the Confucian era and still very much a stratified society where men had all the power. Women had very little say, even over their own children. As I mentioned in the book, if you got divorced your children belonged to your husband. Lots of women suffered and were expected to work for their in-laws.

So I had to modify my behavior because it would be very easy for people to assume I was a “bad girl”. I had to stop smoking and came to never drink. But I’ve always been a feminist. Going to Taiwan was like jumping back into my mother's generation where it was all a one-way street. Men could do what they wanted and women had to toe the line. But in Taiwan I learned not be judgmental and realized I couldn’t impose my views on others. I made good friends with women in Taiwan, though, and they'd tell me their sides of the story.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Did you see changes in the time you were there?

Carolyn Phillips: Yes. I became fascinated by the feminist movement in China, particularly around the 1911 Revolution. Women began to finally gain certain freedoms and I talk about that a little in my book with my husband's maternal grandmother. Before then, women were absolutely uneducated and had zero rights.

And so I started talking to elderly women in Taiwan. In chapter two of my memoir, I talk to Professor Gao, a feminist. I read many books and tried to figure out what was going on in Taiwan, because they, too, were on the cusp of change. The courage and strength of these women is absolutely phenomenal. Women are now increasingly not marrying in Taiwan, and it's also like that in Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong, where women don't need to be somebody else's daughter-in-law and don’t need to have children in order to be fulfilled.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Another thing I loved about your memoir is that you include gorgeous illustrations you drew yourself, along with recipes you learned from your time in Taiwan, your travels in China, and from J.H.’s family. It's really a multifaceted book, and it's going to be difficult for me to read more traditional memoirs after being so spoiled by yours. Did you plan to include illustrations from the beginning? You'd already illustrated your two other books, The Dim Sum Field Guide and All Under Heaven.

Carolyn Phillips: My publisher really wanted to have illustrations. I had originally started out with illustrations in my first book, All Under Heaven, because McSweeney's, my publisher at the time, had asked if I wanted to have photographs or illustrations. I asked about the difference between the two, and he said the cost of illustrations was much less, so I could have more recipes. So I said let’s do illustrations. And because I’m a total control freak, I did the illustrations myself.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Were you trained in art? Your illustrations are so beautiful.

Carolyn Phillips: No, I was never trained in art, officially, although I did take lessons in painting and so forth in Taiwan. I worked at the National Museum of History for five years and we had some of the greatest artists in Taiwan. So I would watch them paint and learned from them. I always loved to draw, although my mom discouraged it. I had my Rapidographs when I was in high school and thought they were the best thing ever. I guess this sort of carried over.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: So with your memoir, it was just kind of a given that you would illustrate it?

Carolyn Phillips: Yes. They really wanted to have illustrations and I think that was part of the sell. They liked the idea that it’s unique. Not too many people illustrate their own books.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Dim sum is one of my favorite meals. It's also that whole experience you write about: sitting for hours in large dim sum stadiums, sipping tea and chatting with friends or family. Can you talk about how you came to write The Dim Sum Field Guide?

Carolyn Phillips: I had my first great dim sum meal in Hong Kong on Nathan Road not too far from the Star Ferry. I knew this American nun who was living in Hong Kong, and she and her sister nun invited a couple of my friends and me to have dim sum. At the end, we got into a huge tussle over the bill, which of course is very Chinese. So these two white women are duking it out in the middle of the dim sum parlor and everybody's practically taking bets.

I was thrilled by the whole concept of dim sum. When you get an American breakfast with waffles, eggs, and bacon, it's delicious, but after two or three bites you wonder if you want to have forty more bites of the same thing. With dim sum you can slowly go through steamed, pan fried, deep fried, and baked, and everything is totally luscious, and I'm drooling as I speak.

The seed for the book came when I first got that contract with McSweeney’s for All Under Heaven. My editor was Rachel Khong, and she was also an editor at Lucky Peach. She asked if I wanted to write something for their upcoming Chinatown issue. And so we came up with the idea of a field guide—like a bird guide book—with sixteen different dishes. When Lucky Peach had the MAD symposium in Copenhagen, they turned the article into a little pamphlet to pass out. While I was waiting for All Under Heaven to finally get published, I wrote to Aaron Wehner, the editor at Ten Speed Press, and told him what I’d done at Lucky Peach and asked if he’d like to do a whole book on this. And he said, “Sounds cool.”

Susan Blumberg-Kason: That came out the same year as All Under Heaven?

Carolyn Phillips: It came out the same day! Only Prince and I have done that. I’m in a good company with The Purple One. It was a thrill. Ten Speed Press took over the publishing of All Under Heaven because McSweeney’s was going through some issues so they did it in cooperation with Ten Speed.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: So I have to ask this because I'm sure readers will wonder about it. Have you ever been questioned on your authority of Chinese food?

Carolyn Phillips: I've really never gotten any pushback, knock on wood. What I have received is a whole lot of love, especially from the Chinese American community. For example, there was a lady who lived in Central Valley in California and she described these cookies that her grandma used to make. But she didn’t know the name. I went through the many cookbooks I have in Chinese. When I finally found a couple of recipes, I asked her if they sounded like it. After several tries, she finally said that’s it. So if I can help somebody like that reconnect with their family, I just feel like I’m doing something right. As long as you're not approaching it as cultural imperialism and if you're doing it with respect and with love and with humility, I think it’s okay.

My role model has always been Diana Kennedy. I think she’s one of the very few white women who has actually become an expert in her field. Even the Mexican government has recognized her contributions, and she’s received the Order of the Eagle.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: It's good to think about all these things because there are so many benefits to having these recipes and these methods of cooking.

Carolyn Phillips: The reason I wrote All Under Heaven was because the foods that my husband and I loved eating in Taipei during the 1970s and 80s were classical cuisines of China—and there are many cuisines in China—that had come to Taipei. We were the beneficiaries of this and ate like kings and queens many times a week. But when we came to the States, they didn't exist. When we went back to Taipei to eat, these places no longer existed either, because the chefs were passing away or retiring. The younger people didn't know what it was they had had. I hope to not only encourage people to remember the foods and to cook them, but also to appreciate them. You can have a great chef, but chefs need to have a clientele with sophisticated understandings of what is being served to them.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: I think Americans have gotten more interested in food in the last ten to fifteen years. It’s a slow process and books seem a good way to bridge that and to get people interested.

Carolyn Phillips: It's a good beginning. Television is also a good way to go. Anthony Bourdain was marvelous in that way. He had that humility and curiosity I think we all aspire to, where he would eat every part of a warthog, or go into a village and eat whatever they served him, which is absolutely the correct attitude.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: You did everything that Bourdain was known for, but decades before, and one of the things you write about in your memoir is cooking a pig head. Anthony Bourdain would have made that glamorous but you did that for your family and friends.

Carolyn Phillips: A lot of it was to just win over my future mother-in-law because she was a real hard nut to crack. But she did love to eat, so I learned to cook the foods that opened her up and warmed her to me. That was a great stimulus, winning your mother-in-law over, especially when she was a warlord lieutenant’s daughter.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Did any books or authors inspire you to write At the Chinese Table? And do you have plans for a fourth book?

Carolyn Phillips: I’m actually finishing up my next cookbook. I can’t talk about it now because I don’t have the contract yet. As for food biographies, there are so many wonderful memoirs out there. My first influence was M.F.K Fisher. She writes more sensually about food than anyone I know. Some men don’t like her. I don’t know why, but to me she always spoke to my heart. Even now I can remember her peeling a mandarin orange and placing the segments on a radiator so that the skins would slightly crisp up before she took a bite. That kind of depth of sensuality is phenomenal to me. Julia Child’s writings are wonderful. Han Suyin’s Love is a Many-Splendored Thing is based on her cross-cultural life. There is also Georgeanne Brennan with A Pig in Provence. I filled up my shelves with people, especially women, who went to another country and sort of lost themselves. I’m really fortunate to be on the James Beard Foundation’s Book Committee. We see a lot of really great food writing and we’re so lucky to live in this world where food writing is appreciated. Kiss a food writer!

Susan Blumberg-Kason: I just love that ending!

Carolyn Phillips: But just don’t kiss them during the pandemic.

A Review of Honey Girl by Morgan Rogers

In Honey Girl Morgan Rogers explores themes of institutionalized racism in higher education, and societal, personal, and parental expectations. The novel follows Grace Porter, who has a freshly acquired PhD, a brooding tri-life crisis, and the foggy memory of marrying a stranger in Las Vegas when she was drunk.

In Honey Girl Morgan Rogers explores themes of institutionalized racism in higher education, and societal, personal, and parental expectations. The novel follows Grace Porter, who has a freshly acquired PhD, a brooding tri-life crisis, and the foggy memory of marrying a stranger in Las Vegas when she was drunk. Despite her uncharacteristically impulsively marriage, Grace doesn’t rush to annul it; instead, she uses her marriage as an escape as she struggles with her mental health and a job market that doesn’t seem to have a place for her. As the story progresses, Grace balances the relationships in her life as she learns about her own boundaries and needs.

One of the strengths of Honey Girl is its cast of characters. Grace does not have a single group of friends that follow her everywhere like a sitcom ensemble. As Grace changes settings, the people around her change too. I appreciate this because one of my pet peeves is when a protagonist attends classes with a handful of people, who also coincidently live in the same building and work at the same establishment as the protagonist, becoming essentially accessories. Instead, Grace realistically has a different group of friends in Portland and New York, as well as separate work friends. This serves the plot well. Not only does it allow the reader to meet many fleshed out characters with diverse gender identities, ethnic backgrounds, and sexual orientations, but it also contributes to the sense of burnout and frenzy, as Grace has social and emotional obligations to so many people. The world of Honey Girl feels full. Even when it is not explicitly described, I imagine the bustling streets on New York and Portland because Rogers establishes early on that Grace is surrounded by people. In this way, Rogers avoids another common romance trope—that of the romantic leads always being alone, longing for each other in some miraculously unpopulated area.

Toward the end of the book, Grace seeks a therapist. While this isn’t an uncommon situation in fiction, I had never seen a portrayed the way it is in Honey Girl. Grace visits a few different therapists, moving on when someone isn’t a good fit for her. This is a marker of growth for Grace, as it shows she is ready to better her mental health, and she is confident enough in her understanding of herself to know when a therapist won’t meet her needs. I found this really refreshing. When I think of the therapists I have seen portrayed in literature, TV, and movies, I think of characters instantly connecting with their therapist, or begrudgingly going to appointments despite a lack of connection. I had never thought about this before reading Honey Girl, but it makes sense to portray “the search” for a therapist in fiction, as that can often be a daunting part of committing to a mental health wellness plan.

While I enjoy the variety in Grace’s relationships—some characters are described as chosen family, others as close friends, and some are new, budding friendships—I found myself wanting more of an understanding of Grace’s wife, Yuki. Yuki is a waitress by day and a radio host and monster hunter by night. While it is clear that Yuki is creative, intelligent, and romantic, I wondered how characteristic or uncharacteristic the sudden marriage was for her. I would also have liked to have seen Grace and Yuki’s initial meeting, as it would have given insight on the bond they have. At the end of the book, Yuki still felt like a stranger to me. It’s true that Yuki and Grace don’t know each other very long, but at one point, they do live together and presumably get to know each better. I would have liked to have felt like I was learning about Yuki as Grace was.

While it didn’t take up much of the word count, as a self-proclaimed sea monster lover, I am compelled to mention how excited I was when the Lake Champlain monster, Champy, made an “appearance” in this book. As someone who has gone monster hunting for Champy and written him into my own fiction, I was excited to see Yuki in action. I wanted to see how much work Yuki put into researching monsters, and perhaps see her interview locals, or maybe even locate Champy landmarks that they must have been around. I felt like this was a moment for Yuki’s personality to shine and to show her knowledge of mythology and history. Instead of seeing a different side of Yuki, the characters sat by the lake and she spoke beautifully and poetically, as she did for the duration of the book, but nothing she said couldn’t have been said back in her studio. Regardless, I still enjoyed “seeing” Champy in this book!

Honey Girl is a joy to read. It’s full of strong, well-developed characters who are funny, fun and kind. It handles topics of mental health empathetically and shows both the relief and stress that can come with diagnosis and treatment. It is a book I have no doubt I will reread.

"If there's a gap then there must be a witness": A Review of G.C. Waldrep's The Earliest Witnesses

The poems read very quietly: poems about the Eastern English landscape, about Welsh saints, about a very particular kind of remembering. There is, as William Wordsworth puts it, "a not unpleasant sadness" in the collection.

Many of the poems, in G.C. Waldrep's collection, The Earliest Witnesses, were composed while walking. In a February 2021 poetry reading with Carcanet Press, Waldrep spoke of the realization that, after suffering from a chronic illness, he might never walk again. In "I Have a Fever and its Name is God," Waldrep is witness to an ailing body, "The nurses place bowls of fruit / around my prone body, / as sacrifices. Not to you, / they explain, / but to the heat you bear." The body becomes holy because of the fever inside of it.

Many of the poems read as prayers, which is not surprising knowing Waldrep's relationship to Christianity. In "American Goshawk," he writes, "The problem / is that I am not able to respond as you demand— / and you, it seems, are not able to respond as I demand, / or would demand. And so we wound one another." This may be an address to a fellow forest wanderer, but because of the first line, "I strode into the woods in a brute faith, certain the forest / would give me what I needed," I read it as an insistence to a divine source: please God, help guide me. The poems read very quietly: poems about the Eastern English landscape, about Welsh saints, about a very particular kind of remembering. There is, as William Wordsworth puts it, "a not unpleasant sadness" in the collection. The North American Goshawk reminds him, "I was no longer in love with my life, or with anyone's." In "On the Feast of the Holy Infants Killed for Christ's Sake in Bethlehem," Waldrep starts, "It is banal to return to the past but a past is all I have" and finishes, rather brilliantly, with "What I love about the past is that it does not break. It is breakage. It is broken." The poems take on a Romantic melancholy. Similar to the Lake Poets and yet also a Whitman like ecstaticism for the body.

Waldrep's work is influenced by Michael Palmer, a language poet who writes, in "Notes for Echo Lake" (Codes Appearing), "Memory is kind, a kindness, a kind of unlistening." I read Waldrep's work as a collection of memories which serve to unlisten. In "[West Stow Orchard (III)]" he reflects, "That is the problem with listening, why stones refuse to do it, / categorically." Waldrep's poems aren't trying to forget the past, but to listen to the memories differently, perhaps both to the silence and the sound. In "West Stow Orchard," we find the speaker limping through an apple forest, "I held silence as in my palm, watched it stretch, flex" and then during this silence, this unlistening, he is able to contemplate time past, "Distance of was. Distance of legible syntax." Traveling with his two Canadian hosts, he is quiet again, "And so I drew from that place a reticence, as from the deck of reticence. It / lodged in my body, guest within guest." He is both a guest to these people and perhaps to this silent intruder in his body, which at times, feels like God itself.

In "Hephaestus in Norfolk," during a stroll under the East Anglican sky where rabbits are his only mammalian company, he writes, "This is all a paraphrase, a voice whispered / but when I asked 'of what?,' all I heard was the sky's / low and level drone" And isn't that the spirit he seeks? Isn't that what the unlistening is for? So, we may hear the space, the silence of our quiet gods. Of all the lines in the book, the one I keep repeating, palming over and over in my hand is in "On the Feast of the Holy Infants Killed for Christ's Sake in Bethlehem," the peculiar and wonderful line, "If there's a gap then there must be a witness." The book is titled The Earliest Witnesses and is a collection that reckons with a personal and collective past. A person who spends considerable time in an old castle. A person trained in music who, in "[Additional Eastnor Poem (III)]" is listening to the objects of earlier times, "history has no grammar, no melody; it is most / akin to the medieval drone." The poem is trying to figure out what winter's antiphon (a chanted sentence before or after a psalm) sounds like and the poet tells us, "Like a doll sewn from scraps of calm." How strange and fantastic. What is poetry but to surprise someone with the possibilities of language?

During the poetry reading, I asked Waldrep if some of these poems were eco-poems. After some debate about the definition of the word "eco," he came to the conclusion that, no, these poems were more conventional. However, I see them as ecologically focused. They are poems of landscapes, of hawks and owls, of stars and sky. But, more than that, they are poems of walking. A body walking through a castle. He spends much of the book thinking about Eastnor Castle, a place where, in "[Additional Eastnor Poem (1)], he "catalogued & numbered the various smokes as they emerged/from the plain beyond the ridge.” In these poems, he often walks with a companion. Someone he speaks to, but never names. I am left wondering if it is the person whose life he is "not in love with" or if perhaps not a person at all, but a guide with a spiral notebook. He continues in this same poem, "Tell me more about the spiral book, I asked, but you would only / shake your head. 'I can't describe it more clearly than that,' / you said." The poem ends with a metaphor on faith, "We can't see most stars by day."

In an interview with Image Journal, Waldrep speaks of the difference between poetry and prose, "I’d say poems exhibit a level of tension on language interior to the sentence, rather than among or between sentences. . . If I can discern that tension, it’s a poem. If not, it’s prose." There is a tightness to Waldrep's work. A sense that the poem is building itself line by line. Sometimes, the poems don't move forward. They stick together. Lines glued within themselves. As I walked through the poems, I found a lovely definition of poetry, in "St. Melangell's Day Eastnor (1)" to "Say a poem is like that, / a bit of silence the world acceded to, for a finite duration."

His work reminds me of the British artists Hamish Fulton and Andy Goldsworth. Both use nature as the medium for their work and in doing so create mystery. Parts of Waldrep's work I could understand and parts I could not. And yet, he creates a spiritual universe that I can understand very well. It is the mystery of poetry. In Fulton's work, he spends days walking, alone, silently and then presents images / maps / data of the walks. Goldsworthy takes fallen leaves and builds wondrous patterns with dark holes in the center. Waldrep's poetry falls somewhere between these two artists' work. He is asking us to walk quietly, to speak to the God inside of us and perhaps to find in his poems, these dark holes of intrigues: spaces not quite comfortable and yet places where we feel at home with ourselves.

Frying an Egg: An Essay by Melissa Wiley

This essay was originally published online in (b)OINK.

Sometimes she separates her pinkie toes from all the others, making them stick out from her sandals. To her, they resemble the arms of incarcerated men reaching through their prison bars for women. She does this to shock onlookers, though usually she has to point down at her feet for them to notice. She takes comfort knowing all her toes were once webbed in amniotic water. She likes imagining when the skin between them was stitched into something seamless. Their prior wholeness inside her mother.

She eats eggs on an almost daily basis. She never scrambles them, however, because they will only scramble themselves later inside her stomach. Instead, she dangles a fork over the frying pan as if it were a lone pinky toe or finger. She touches a tine to the yolk so it thins and disperses but retains a wobbling roundness. Some people eat only the whites, but she eats the ovum. She eats the dark sun that might make her into a chicken woman.

Even those hens that do nothing all their lives except sit chaste inside some henhouse some farmer has built for them still undergo the birth-giving process. Unfertilized eggs travel the same pathway as those bearing the mark of a rooster. Unfertilized eggs are no larger or smaller than those stirring with fragile life inside them. To a hen, giving birth feels the same as what you could call chicken menstruation. Each emerging egg shimmers the same with promise, however lifeless.