Far-ranging and Intimate: A Review of Tara Lynn Masih's HOW WE DISAPPEAR

How We Disappear encompasses a range of time periods, locales, and styles: two-page flash to novella, realism to ghost story, historical fiction to modern American myth. Luscious descriptions of the natural world help to illuminate a theme bonding these thirteen diverse stories: the mysterious human heart in search of itself and its place in the world.

Tara Lynn Masih’s impressive second collection, How We Disappear, encompasses a range of time periods, locales, and styles: two-page flash to novella, realism to ghost story, historical fiction to modern American myth. Luscious descriptions of the natural world help to illuminate a theme bonding these thirteen diverse stories: the mysterious human heart in search of itself and its place in the world.

In the perceptive “Those Who Have Gone,” a weary Elizabeth travels from New York to Arizona in search of something different. Almost immediately she meets Blaze, a local man who looks like her ex-husband and has her pegged from the start. More dialogue than is usual in Masih’s stories effectively develops Blaze’s character, while Elizabeth’s inner life is stated in quiet, compelling prose, “The signs of death and violence before and behind her told her to leave. But something about the man told her to stay. So she stepped sideways in her mind, tried to accept his casual demeanor as her own.” As Elizabeth contemplates the land she’s getting to know, the story’s setting and circular structure deliver even deeper meanings. Some disappearances are forever; but once you know how to look, you can spot their traces.

Traces left behind are a major part of “Notes to THE WORLD,” the story of Grigori’s first hunting season, mere weeks into a months-long contract with a co-op. Told with convincing detail, the survival skills learned from his mother and his neighbors will be tested, nothing euphemistic about what it takes to stay alive in the Siberian Taiga. After a near-fatal accident, recovering in a cabin he’s stumbled upon, Grigori discovers a stack of numbered notes written by Desya, daughter of a family of persecuted Old Believers. He’s drawn into her story of having to live in hiding. He shares her losses and her aching loneliness. “His fear was with him each morning when he woke up in his village to the birds and white sun that fought to penetrate the northern mists. It settled on his chest so hard sometimes, he struggled to breathe and be part of life once again.” Grigori’s growing relationship with Desya’s unseen presence parallels the reader’s experience, a complex blend of immediacy and time-travel.

Even more complex in themes and imagery is “An Aura Surrounds That Night,” an immersive account told by Mercy, the oldest of so-called Irish twins, the dynamic of their farming family an echo of the Biblical Esau and Jacob. The short opening section deserves to be fully quoted, but here’s a snippet: “One memory was once locked up, hidden, in the same way these small colored bits of rectangular prophecies are folded into doughy shells. These papers that stay curled up…until we…tear them out of their protective shelters and examine them privately or read them aloud.” The narrator’s memories are replete with sensory details, such as a childhood outing with the sisters wearing “…dresses ironed so recently that you could still feel the warmth where the iron last passed over the cotton.” The wise woman of their coastal Long Island community hints at a solution for those who leave and for those who stay, applicable to other characters in this collection. The whole last section is a lyrical, place-laden resolution of healing, a way to move forward after tragedy; a rare and precious thing, for the reader as well as for Mercy.

Rarer is the writer who leaves no traces of herself, allowing the characters to wield their own singular voices, yet Masih has achieved it in each of her far-ranging yet intimate stories. Some characters yearn to disappear, some for only a time, ultimately realizing their paths follow or align with another; some characters have no choice. But they all do what the best of fiction does, they stay with the reader.

An Unclouded Eye: A Review of IN OTHER DAYS by Roger Craik

These poems will come back to you again and again; not to bite you, but rather to whisper glories in your ear, understated glories of remembrance and love.

Whether it’s the sprawling oak of a contemporary Odyssey, or a mere seedling like Stevie Smith’s Croft, a poem must earn its right to the name. Readability—that is, a rhythm of sorts to carry you through—is a given, along with originality and expressiveness; but for the thing to have substance, surely two qualities are essential: it should have integrity, it must have heart.

Roger Craik, Professor Emeritus of English at Kent State University, Ohio, knows this; knows his craft inside-out. The poems here are not dramatic, not intended to startle or outrage; they are not clever, tricksy poems delivered from under a mortarboard, nor are they prissily poetic or drowning in molasses. Disappointingly perhaps to thrill-seekers, polemic-eaters and those of a righteous or overly sentimental disposition, you will find here only poems that are considered and quietly commanding. There is an unobtrusive artistry at work in the construction of them, a building up of colour, detail and honest feeling. They will come back to you again and again; not to bite you, but rather to whisper glories in your ear, understated glories of remembrance and love.

Craik was born in England, in the county of Leicestershire which was, and is still, largely rural. The character of the place is effectively summoned in the early poems by the naming of villages—Peatling Magna, Peatling Parva—just as people from his boyhood are fixed in time simply by their names; wonderfully resonant names like Marjorie Marlow, Brownie Neave and, magnificently, Florrie Mist. Local history, personalities and events are casually dropped into the mix for detail and atmosphere, and to give us a real feel for the environment in which Craik grew up. Nostalgia can be precarious for a poet, it can all too easily soften the senses and distort the truth, resulting in a poem lacking backbone, lacking interest to all but the writer. But Craik is far too good a poet to fall into that particular trap; his is an unclouded eye reflecting experiences that are, perhaps, in some way common to us all. I’m thinking of the poem “Lewes,1966” where he is playing alone:

The taut green

tennis ball spinning from my fingertip,

spanking the hot patio, half-volleying

up against the brickwork and

soaring in the sky all over England

to clasp itself in my palm

again and again and again.

The repetitive, trance-like throwing of a ball by a youngster contemplating the coming of a world of danger and possibility, represented by a vast sky, is a nice image skillfully presented.

He goes on to recall a series of quiet moments of revelation, testament and emotional impact in a way reminiscent of someone pulling over in the car to take a moment, to reacquaint himself with those things that have contributed to his character; a sort of reset, I suppose. Among a fascinating miscellany, we learn of his travels in Turkey and of the detached voice of an old man calling on his god while walking through reeds in the mist, and of a moment of loneliness in Romania. There is an elegantly composed deliberation on the gymnast Olga Korbut competing in the ill-fated 1972 Olympics in Munich, and a lyrical hymn to Burrough Hill, with delicate reference to his self-realization. Craik moved to America in 1991, and “New Year’s Eve,1999” is an engaging contemplation of the old country and his ancestry peppered with fragments of family history, and ending with the exquisite “The last of the sun / is crimsoning into the world.” I was taken by a curious poem telling of an outsider moving in to the village and complaining of cocks crowing and cows (described wonderfully by a local as chorus girls) mooing, which contrasts with a rather sad consideration of an adolescence fueled by the songs of Leonard Cohen, his voice “graveling down the years”.

That phrase prompts me to offer, without context, another of the author’s pleasing illustrations: this time his description of the pronoun “we” in one of his pieces:

Plump gelatinous

capsule of a syllable

smooth as halibut liver oil.

If that little aside doesn’t define a real poet, then I’m not sure what does.

Above all there is a subtlety, a hesitancy almost in these poems. A sense of the unidentifiable, of something behind the veil, is presented time and time again, and it’s a device, if you can call it that, which is hugely effective. This quality of suggestion is nicely demonstrated in the poem “That Early Evening” which sees the poet walking with a girlfriend along a disused railway line in his native Leicestershire fifteen years ago. He can still picture the cows and their calves lumbering over, these guileless creatures at the gate:

each one’s brimming luminous gaze

drawn to me, drawn to me, betrayed.

It’s oddly touching, and the inventive but entirely convincing language (the cows “in a jostling hotness, nostrilling hard”) catches the moment and enhances the mood beautifully.

This holding back gives way, as it were, only in the last lines of an affecting poem about his mother’s illness. He reflects one Christmas on the number of cigarettes she has smoked over these thirty years, and those she has yet to smoke. How they are:

… slowly killing her, in the other room,

while I’m half-drunk on gin, writing this in tears.

We get to hear more about his mother in the final poem of the collection which deals with her subsequent death and funeral in an almost conversational but deeply tender manner. It’s opening lines are a remarkable summing up of mourning:

This is no grief I have ever known.

It is as if

a child has drawn a wandering unbroken line

through all the days

I am still to live.

The honest simplicity of the words only serves to make them more meaningful, more entirely apt. They embody those very qualities mentioned at the top of this review.

Long after the work of more showy poets loses its sheen; after the cliches have worn themselves thin and the clever conceits have surrendered their fragile appeal, these nuanced and dare I say it relatable poems, with their thoughtful and sympathetic grace, will stay long in the memory. In Other Days is a finely drawn and unhurried remembrance magnifying the tangential and hinting at the quietly momentous. It is an impressive piece of work.

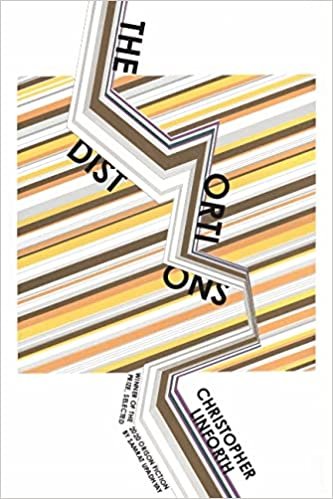

Semblance of History, History of Semblance: A Review of Christopher Linforth’s THE DISTORTIONS

One gathers a sense the English language lacks words to echo back “homecoming” in its proper fullness of color, so it is good then how Linforth’s stories fill in this gap if only ineffably so.

With his third story collection Christopher Linforth returns to his past in Zagreb as a source for fiction that probes the literal and psychic fragmentation of Yugoslavia. In twelve stories, including two works addressed to each an erstwhile lover, The Distortions stages ethnic Bosniaks, Croats, Serbs and others as they attempt to piece their relations sometimes to family and sometimes to interlocutors on the world stage. Piecing entails reading history even when history’s evidence seems distorted or at least too much to bear.

Characters are often readers of history in one guise or another—photographers, gravesite dwellers, philosopher-hopefuls, a “preservation assistant,” and a ghostwriter—all trying to make the pieces fit. The titular story pits the choice of immigration to the choice of staying behind insofar as one fails to grasp the other’s sacrifice. Here a failed journalist struggles to motivate his great uncle to move to New York over twenty years after the disintegration of his Sarajevo and family both. Together they face an immigration bureaucracy which, far from a Kafkaesque withholding of knowledge, asks that they search archives on and on to equally fruitless avail. This previews a returning theme implicit in the collection’s title: characters search to reconcile the rifts between past and present. History and family trees distorted, the missing pieces feel often beyond reach.

Fast forward to the capstone story: “May Our Ghosts Stay With Us” features a film scholar ghostwriting his murdered grandfather’s autobiography after having found a diary. Compared to a previous story lamenting that communication is fraught—“words are just black marks on a page”—our scholar turns toward and away from nihilism and a Derridean anxiety, by his own admission, that representation is “adrift in time.” “Life” one character says “has nothing to do with theory,” yet how can one make sense of “flecks of gray” or “grainy images” without speculation and when meaning invests them only half-way? Grayness for narrators often refers to distortion as well as backdrops of cities in which “Communist concrete” is a characteristic trait.

Against an absurdity that history is bound to eternal recurrence, characters hope they can—perhaps maybe—intervene in its rush if only to save a single person from vanishing. While for those of whom the wars are a thing of the past, the prospect of losing another loved one still tends to shake the past loose to the present. The effect is that dissolution never goes away.

Linforth crafts time and place subtly. A peripheral character’s age, a gesture to a sitting president, an iPhone. The literal distance from the wars becomes instead a task for characters and readers to take on. Rather than confront warring headlong, Linforth writes conflict around war’s periphery and aftermath. Forgotten landmines and wounded animals astray become points of contact whilst war looms in background or memory. Reunited with news reportage, archival files, passports, letters, dolls, postcards, maps, diaries, and more, characters in one extreme try to “restore them to their pure, original state” or, in another, interpret in them futility.

The trauma of killing or failing to save one’s countrymen is less rendered through militancy than vicariously through the rescuing or doing-in of an innocent animal. In “Fatherland,” for example, a new father searches for a metal spade once used to bury a bird he had bullied a boy into killing when they were tasked with defending a border. This echoes back to “All the Land Before Us” in which a teenage boy attempts to save face with a Hungarian traveler to whom he is attracted while she fails to save a dog he had shot. Similarly, this motif of freeing or ignoring the embodied pain of others lines up with Linforth’s scrutiny toward preservation. There is an insight that photographers contemplating the past frozen into an image also question whether photography saves bodies from time’s indifference or simply records their powerlessness, at times their perversion.

Another subtlety not to overlook is Linforth’s writing of split commitments. It is not just the immigration-versus-staying-behind of the first story on display. Folded into stories is a tension between committing to various sides: one continent over another, one family over another, one economy over another, between an old and new millennium, between analog and digital even. These contradictions cling to a dialectic of enchantment and its loss.

One would be remiss to discuss this collection without attention to its characterization. Each story contains wholly new people, whether nostalgic or forgetful, cosmopolitan or national. One memorable foil is of a veteran of the Croatian army who begrudgingly hosts an emigrant-cum-businessman around town. Their restrained animosity begs them to reconsider how they can each be “men of the world” in their own way. Some characters are jaded with intellectualism yet ready still to cash out its clout in an academic or artistic career. Through bold decisions others even show vanity, infidelity, impudence, and as the collection progresses, a ghostliness “impervious to those around” them. While though some stories rely on a character’s flaw to hurl forward their plot, one could not say Linforth falls into the illusion that an isolated human agency is what makes a story.

To put it otherwise, Linforth focuses craftsmanship into the relation between character and world. A relational approach also informs the logic of his endings. The arc of many stories aims toward a homecoming, and each ending makes an iteration of one, be it partial or thwarted. These endings resist a clear or sentimental homeliness. Instead they destabilize what grounds here from there, teaching readers to contemplate dislocation. One gathers a sense the English language lacks words to echo back ‘homecoming’ in its proper fullness of color, so it is good then how Linforth’s stories fill in this gap if only ineffably so.

All the while thematizing distortion, Linforth writes with a clarity that, in service to characters, never need slip in some smokescreen for clever effect. Time’s passage, will, intellect—for characters these are bound to their terms in an honest-heartedness recalling Andre Dubus. It is with this balance between character and concept that The Distortions invites rereading. Between imperfections shading the histories that characters traverse in gray, there are still moments of clarity to be found, moments sometimes rendered in landscape or “reds and whites” brimming to fullness. In the lives of Linforth’s characters, what can seem fragments of a worldly cipher might instead be a sign—that wholeness has little to do with appearances and a lot to do with reappearing for others.

Checklist, Recipe, Yellow Brick Road: A Review of Pamela Wax's WALKING THE LABYRINTH

Pamela Wax, whose life is a found poem, “pretends to be who she is, tries to be normal, spills words all over herself and loses her names”—an apt description of so many poets.

Pamela Wax is a poet-rabbi and while she produces first-rate art, bibliotherapy also appears to be a priority. Walking the Labyrinth is an apt metaphor for this odyssey. While this book purports to be a series of elegies, it is also a deft memoir that avoids the heavy-hand of an incessant first person. Its emphasis is less memoir than spiritual autobiography, but the occasional first person explorations subtly hold a place for both her own idiosyncrasies and struggles as well as her readers: she creates space for your I and for my I.

The persona “pretends to be who she is, tries to be normal, spills words all over herself and loses her names”—an excerpt from “The Woman Who: A Found Poem,” says it all and says it best. We are offered frequent glimpses into the panoplies of pain associated with this quest for virtue—often in tandem with the duties of family and tribe. The grief and consequent suffering accompanying this attainment of virtue is resolutely probed.

Her elegies for her brother Howard and many others act as both catalyst and muse. Her awareness may invite us all to stop working so hard at virtue, but also reveal Wax’s prime compulsion—a longing for a guaranteed “checklist, a recipe, some yellow brick road,” a map or atlas revealing the important “to do’s,” all of which reflect her need for a world in which she can attain righteousness—where she can be safe and in control—a world in which she locates the proper path to attaining goodness. This is often followed by worry—the need not to get it wrong. It being life, with all its attendant uncertainties: all the self-blame, remorse & grief, especially the guilt inherited by those who sacrifice themselves for so-called higher or holy quests: our spiritual leaders. Our gurus, priests and rabbis.

In a moment of insight Wax describes a cartoon caterpillar on a couch being advised by her butterfly therapist: “the thing is, you really have to want to change.” This comical image and dialogue triggers a listing of internal guilt-trips. She goes on to detail minor masochistic behaviors she indulges in, in order to undermine any sense of entitlement or right to claim grace. In this psychic no-win situation her sense of humor & attempts to reach for optimism are laudable, yet the pathos remains notable.

Wax defines herself through her tribe, yet avoids religious zealotry; however, details about Judaic traditions might distance some readers who are not familiar with a diction that includes words like kvelling, shomer, hora, and kaddish.

A poem that helps clarify cultural differences is “I Am Not Descended from Stoics Like Jackie O.” as she explores the reality of being “descended from Eastern European Jews who turn their prayers towards a Wailing Wall because the danger & despair are everywhere and eternal and what else did they know to do?” Is this book Wax’s personal wailing wall? Possibly.

Occasionally Wax slips into manifesto, but still manages to hold fast to her suffering: “when my guilt takes a form other than flesh. I mix it with naked rage because never again is pitched capriciously in the ominous night tent of the world—feeling all this almost guiltlessly on sunny days.”

Her obsession with virtue is portrayed in her gently self-mocking poem “I Keep Getting Books About Character.” As she reads and rereads many translations of Paths of the Just & Duties of the Heart, we are treated to a light-hearted bit of satire, best illustrated by a sign in her office that reads:

I want to be a better person but then what? one queries. A much better person?

She romps often with sound and enjoys occasional rhyme in her pithy description of her readings of “Medieval tomes in pious tones.” Her zig zags between despair and humor keep her afloat and help the reader process this confessional.

The format varies occasionally as in her odd first poem “Howard” which she divides into two sections: part one is titled “I. How” and part II. is “Ward.” This playful character sketch introduces us to the book’s central elegy for her brother Howard, a suicide. She returns to this formatting later in the book.

Walking the Labyrinth is the mother of all elegies—it holds too many to remember or list. It presents us somehow with a life lived primarily through a lens of loss but without the anticipated and attendant nihilism. It is not an easy read but well worth the effort, even if your life is not steeped in family ritual or religious legacy. Dive in. See if you can swim. It may be best to prepare for reading a book of elegies by not being prepared—if preparation is even possible. Let its stream of consciousness flow. Drop control needs. Practice what the poet finds so difficult. Relinquish her needs for “checklist, recipe and Yellow Brick Road.” Step into her journey. I feel fortunate to have met and eventually to have groked my first rabbi, Pamela Wax. Join her, as she invites, us, much “like Rumpelstiltskin,” to “weave seaweed into song.”

Lit Pub is now closed to submissions . . .

but we’ll reopen again on Aug 15, 2022. See you in our Submittable then!

Hello,

Lit Pub is now closed to submissions. But we'll reopen on Aug 15, 2022.

In the meantime, please take care of yourselves and each other, and read as many books on your to-read pile as time allows.

We'll see you next (academic) year...

Love,

Lit Pub

Something is Afoot: An Interview with Andrea Ross, Author of UNNATURAL SELECTION: A MEMOIR OF ADOPTION AND WILDERNESS

Some of it is recklessness, the recklessness of youth, and also the adoption loss of self. I felt like I needed to pitch myself against the elements (snaps her fingers) to feel alive, to prove that I was worthy of walking the earth, so that was a big part of it, like testing myself against the elements, what can I do, how far can I go with this till I feel like I am deserving, like I'm worthy somehow?

Andrea Ross’s debut book, Unnatural Selection: A Memoir of Adoption and Wilderness (CavanKerry Press, 2021) explores the rewards and dangers of exploring the natural world, living an unconventional life, and questing for ancestral identity. This suspenseful read is a surprising and poetic yet accessible narrative. As an adoptee, I was attracted to the subject matter, and discovered an elegantly structured and nuanced book that relies on pacing and imagery. It is a memoir devoid of confession and cliché, a feat as deft and daring as the two interconnected experiences Ross describes: living as an itinerant back woods nature guide, while searching for clues as to her family of origin. The Grand Canyon and the canyon of sealed records mirror each other, and she describes facing them with the same curiosity and fortitude.

In the last year, adoptees have made great strides in recentering the adoption narrative to focus on the people most affected and most ignored: adoptees themselves. Writers, filmmakers and podcasters have gone public with meaningful works addressing an experience that the culture both glamorizes and illegitimizes, one that makes detectives out of ordinary citizens as we seek information and connection that the rest of the world takes for granted: ancestry, heredity, and family. I took special interest in discussing these powerful shifts in perspective with Ross, as much as discussing her craft.

We spoke in person on March 26, 2022, during the last hours of AWP 2022, after she moderated a panel called, “Each Book Another Me: Mapping the Progression of Self Over a Career.” A mix of fatigue and buzz, adrenaline and soul, filled the halls of the Pennsylvania Convention Center, as friendly maintenance workers moved the loiterers like us toward the doors.

During the panel Ross introduced her work this way: “My first book is called Unnatural Selection: A Memoir of Adoption and Wilderness… it maps the human need for belonging both from an adopted person’s perspective for belonging to community, belonging to other people but also belonging to landscape: the idea of landscape as a surrogate for lost family, landscape as the body of the beloved and landscape as a living breathing entity which we are in relationship with.”

*

KFK: So in the panel you reveal that this memoir started as a book of poems.

AR: I can send you some of them if you want to take a look at how the poems and the prose interface with each other.

(The corresponding poem and prose excerpts are at the end of this interview.)

KFK: I would love that. It was interesting hearing you talk about how, because of audience and message, that it had to turn into prose.

AR: I'm glad you caught that. My memoir has a certain reader in mind. I wanted to explain to people who aren't adopted or haven't been touched by adoption, the particular brand of loneliness that adoptees experience, especially when they're from closed adoptions in which they're not allowed any information about their origins. The book I'm working on now has a completely different audience and I think that as a writing teacher we talk all the time about who is your target audience? What kind of background information can you assume they have? What do you need to tell them? What kind of language or jargon or vocabulary do you use?

I thought, “I really need people to get the message and it's not coming across in poems even though I just spent two years working on them.” But it took a lot longer than that to write the book as it turned out.

KFK: How long did it take?

AR: I would say beginning to end probably 10 years. I was also raising a small child and trying to launch my career as a teacher and so I didn't have a lot of time to devote to it, but also a lot of it was just really hard stuff to go into and I had to pace myself because I would just get sad and I didn't want to go too dark and not be able to pull myself back out. I would set aside time for writing the really hard stuff and try to compartmentalize, so yeah it took a long time.

KFK: So you saying, “This is going to be really hard to write…” I have to say I had this book sitting on my nightstand for a week thinking, “This is going to be really hard to read…” because as you know I'm adopted, too.

AR: How did you find it when you did dive into it?

KFK: I felt… lightened. It was a great feeling… So tell me about your three semesters with poet Lucille Clifton.

AR: I mentioned in the book I was not an English major or a creative writing major as an undergrad, but I did like to write and so I took an intro to poetry class. Once you've taken the intro poetry class at UC Santa Cruz, you were allowed to try to get into the advanced poetry class, but you had to submit a portfolio to be considered. I imagine there was some pressure on Lucille and the other professors teaching that advanced class to only accept people in the major, but she said she would just kind of meditate on people’s manuscripts and pick the ones that she felt that were people who had something that needed to be spoken, and somehow that happened three times.

She's sort of a patron saint because I don't know what I would have ended up doing if I hadn't had the boost from mentors like her. It really was kind of like sitting in the room with a prophet because she would just say these things that were so profound. She was such a national treasure and she touched so many people. I just felt super lucky to have had that time with her.

KFK: Did you read Guild of the Infant Savior: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book by Megan Culhane Galbraith?

AR: I did.

KFK: What do you think of it?

AR: I liked it! Megan and I have been in contact ever since we realized that our books were being published at the same time. I like that hers is so different than mine. It makes me feel more secure that mine has its own niche but interestingly so much of it is just saying something similar, the closed adoption stories of people just really needing to know who they are and not having access to that. Then the next part of the story is if you do search we all seem to have the same fears and hopes, that they (our biological parents) might be dead, they might reject us, they might be the most amazing person… Or we might have the Kunta Kinte “I have found you!” moment.

We all have that range of fears and hopes around reunion, but then she had a completely different experience with finding her natural mom than I did. They were really into each other at first, and now they're estranged. Mine has been much more even keeled than that. I never felt like, “Oh now I understand why I am who I am.” I didn't and I don't really see myself reflected in my natural parents so much, but nonetheless even though we're super different and have really different politics and values, they're all really committed to being in relationship, even though it's not super close.

I get envious when I hear stories of people who were like “I look just like them.” But in terms of the best possible outcomes, I think I lucked out. I've been in reunion with my natural mom for 20 years. That's pretty unusual. Often reunions run their course in less than 10 years, partly because there's no map charted for that relationship and so it's just really hard to figure it out. I think a lot of times somebody just kind of drops off. It's probably not unlike what happens with some open adoptions these days where people go into it with good intentions and wanting to do the right thing for the child by keeping everybody in contact, but then it gets hard because you're parenting somebody else’s biological child, or you are the biological mom and you are coming to grips with, over and over again, the fact that you have relinquished your child. I think it's similar in an inverse way.

KFK: There’s trauma in both staying in touch or being apart. “Adoption is trauma.”

AR: So much trauma.

KFK: That’s still considered “a theory.”

AR: How's that for those of us who have lived it? We know that it's not just a theory.

KFK: Did you see the documentary Reckoning with the Primal Wound? Are you part of The Adoptee Army?

AR: Yes and yes. Did you get your name on The Adoptee Army list at the end of the film?

KFK: I was late to the game, but when the film gets fully released, I'll be on The Adoptee Army list.

AR: It was so gratifying to see my name and to see so many names on that list.

KFK: It's growing and growing.

AR: Such a good idea that she (director Autumn Rebecca Sansom) had to just make that list in the credits. I was telling a friend of mine about it recently. She said, “It kind of gives me chills… it sounds like the Vietnam memorial, except that was everybody who died and these are the people who lived, but are lost…” So it’s a different kind of reconnection…

I found out about that film because I was asked to be on the podcast called Adoption: The Making of Me, which has been going for about a year. The premise is it's two adopted women who are about my age, mid 50s, who have been friends for a long time and they decided to do a podcast in which they would each read a chapter of Nancy Verrier’s The Primal Wound, discuss it on their podcast and then bring in a guest whom they would interview.

They brought me on and said, “We saw that Nancy Verrier blurbed your book. How in the heck did you do that because we want to contact her!” I totally cold called her and she was just so generous. They're like, “We want to bring her on because we're reading her book!”

They contacted her and she got back to them eventually and she told them that this Reckoning with the Primal Wound film was happening, and they told me.

Just like you mentioned in your email, something is afoot. I don’t know what it is yet, I am really looking forward to finding out, but something is afoot with the adoptee community and just with adoption in general and the way that people are talking about it and exposing things.

KFK: My thesis or theory is the idea that The Primal Wound was published in 1993. It was such a groundbreaking book, to acknowledge that infant adoptees had suffered a loss, that we are not blank slates. I started going to Joe Soll’s Adoption Healing Network support group in New York City around that time. I think it's taken us this long to get well enough to tell our stories, to make art, to be open enough. I’m also not sure what it is, but it seems like since the last generation did this work that helped us get well, that's its now our time.

AR: Megan and I are exactly the same age, and the podcast women…

KFK: Me, too.

AR: There's something about this coming of age, into the age of “no fucks left to give.” Like fuck all y'all, I'm gonna speak my truth! There's something about being over 50. Just suddenly, not suddenly, but gradually, we've matured and learned that we just have to live our lives the way that we want to live them and if that means telling hard truths, then so be it. That is really interesting, that we are all the same age.

KFK: The Summer of Love, right?

AR: I thought maybe that was my genesis but my natural mom was so conservative she couldn’t have even known what that was, but she was having sex anyway as people do.

KFK: Surprising who has sex!

AR: Almost everybody, turns out!

KFK: You handled that so well in your book. You left a lot off camera, but we knew you were being pretty wild in many ways. I like that.

AR: People always ask me, “What's it like to have people know this really intimate stuff about your life?” And I’m like, “You don’t know the half of it.” I didn't really want it to be about my sexuality, but part of that was about the search for self, trying to be fulfilled through in relationship with other people, especially dudes, yeah, a lot of bad boyfriends…

KFK: A powerful scene in the book was when you found the wounded hiker. I thought that if this story couldn’t get any more wild and dangerous…

AR: The more time you spend out in the wild the more likely you are to come across the extraordinary, whether it's something really scary like that or something really beautiful… I was squatting to pee in Alaska when I was out backpacking and I looked up and there was a wolf standing there, the only time I've ever seen a wolf. The wolf checked me out and walked away. I never would have seen that if I hadn't been out backpacking in the Alaskan tundra. That happened one day out of the hundred days that I was out there.

KFK: You are so courageous to do these things! I love the outdoors but…

AR: Some of it is recklessness, the recklessness of youth, and also the adoption loss of self. I felt like I needed to pitch myself against the elements (snaps her fingers) to feel alive, to prove that I was worthy of walking the earth, so that was a big part of it, like testing myself against the elements, what can I do, how far can I go with this till I feel like I am deserving, like I'm worthy somehow.

KFK: A great line in the book is, “Participate in your own rescue!” That’s a sticky note on the refrigerator line.

AR: (laughing) That one just got handed to me. The river rafter really did say that and I remember being just puzzled at the time, like how can I possibly participate in my own rescue? I'm sitting here in the Grand Canyon in this freezing cold water, I just got flipped out of a boat. I can't participate in my own rescue and then of course it's just such a direct metaphor for what we do as adopted people as wounded people, people who have gone through traumas. How much do we have to freaking participate our own rescue? Well turns out a lot. Like you were saying about going to the adoption groups and healing yourself, like it doesn't really happen unless we do it ourselves.

KFK: I think if Reckoning with the Primal Wound gets picked up on Netflix or Hulu or HBO then people scrolling will actually learn something about themselves or their adopted family members. It's hard to get someone to pick up a book.

AR: I found it so powerful the way that she was able to field the perspectives of so many different parties involved in the adoption constellation. Just to see a sibling, her bio sibling, grappling with what that meant. To be like, “suddenly I have this sister.” I had the same thing with my half-sister and it's hard for her. I think getting that validated is really important, just as much as it is for our experience to be validated.

KFK: Somebody in the chat room after the Zoom film screening said, “I had a failed reunion! Why do you have to keep telling me Cinderella stories?” That felt like “ouch.” We have to acknowledge our privilege that this reunion worked out.

AR: There has to be ways for people to deal with that. Like what Megan is dealing with. That’s got to hurt. A lot.

KFK: The empty picture frame is in the book more than once. It's very interesting it wasn't just to end the book. She wrote, “I was not allowed to use this photo” under it.

AR: It's so emblematic of the rest of our lives before reunion. We aren't allowed to use that because we're not allowed to have access to our own stinking birth certificate. I just got mine four months ago. I was doing an article about how it's done on a state-by-state basis. It’s a giant mess and up until only like five or six years ago Colorado where I was born did not allow it at all and then the law changed. I was like, I haven't been keeping up on my homework and so I just went ahead and sent away for it and got it. It was weird.

KFK: Did the article find a home?

AR: It was published in The Conversation. What's cool about it is that it gets picked up by lots of other outlets so when I Googled my article after it was published on The Conversation and all these other outlets had picked it up, so it goes out into the world in a way that it's hard for writer of my platform to otherwise do.

KFK: Congratulations on the book and now your article! What’s next for you?

AR: My next book is more joyful and it's about women and friendship and the outdoors, so my target audience is people who want to experience that joy.

*

Andrea Ross did send me two unpublished poems that later became chapters of Unnatural Selection. Here is an excerpt from one, and an excerpt of the chapter of the memoir after it.

The Skull

(This event is referenced in Unnatural Selection’s chapter called “Ruins and Ladders”)

A gratefulness.

*

Nothing exists except the present.

A foothold—

We’re always experiencing a present moment.

sandstone, the Navajo sandstone.

The past and the future are simply ideas.

Footholds in the sandstone’s face: each a fist-

shaped niche, deep as a toe, a couple of knuckles;

We are not subtle enough to have a science of becoming.

a foothold is a handhold.

Nothing is ever one thing or the other.

*

Excerpt from Unnatural Selection: “Ruins & Ladders: Navajo National Monument”:

“In my little tent that night, missing Don, I distracted myself from my preoccupation with the cattle by envisioning the footholds and handholds I’d seen chopped into the gritty Kayenta sandstone during my descnt into the canyon that day. Known throughout the desert southwest as Moqui steps, they are prehistoric pathways, climbing routes carved by the Ancient Puebloans. I knew it was important to leave any archeological artifact alone so that it might be preserved and appreciated by future generations. But were the steps artifacts? All I knew was that they called to me. I desperately wanted to put my hands and feet into their small recesses to see how they fit, to find out where those hanging cliff trails would take me.”

Love, Graffiti, & Audacious Sentences: An Interview with Jackson Bliss, Author of AMNESIA OF JUNE BUGS

Amnesia of June Bugs is both a scathing critique of the damage we cause each other but also a love song for the endless beauty of this world and the importance that love can play in protecting, nourishing, and saving ourselves from ourselves.

Bonnie Nadzam, author of Lamb, interviews Jackson Bliss, whose debut novel, Amnesia of June Bugs, was released recently.

*

There are so many things I love about Jackson Bliss’ debut novel, Amnesia of June Bugs. In the first place, there is no voice like his voice, which is totally outrageous and utterly unapologetic in its audacity. In the second place, the content is as unexpected as the form: a Chinese American NYC graffiti revolutionary and his mixed-race partner (a tender elementary school teacher), painstaking level of description in every punk rock gastronomic feast, and the ruthlessness of Jackson’s embedded love stories, which always slay me. Finally, and maybe best of all, there is a tremendous, fundamental act of rebellion in this story’s formal experiment.

One of the curses of modern technology is that every single experience of beauty must be offered up to the great digital ledger—fixed in time and space, gathering data—as if the stutter of experiencing that moment a second (and third, fourth, fifth) time, wherever it lands online or in our devices, becomes the only thing that matters and makes us human. Jackson Bliss takes one such instance—one snapshot in time, as it were—and explodes the frame slowly, one page at a time. This novel is really an endlessly arising and endlessly unfolding human story that, for all the suffering at its core, remains one of community and empowerment. These are individuals who are as present in their joy as they are in their suffering, which made me curious about their author, whom I’ve still not met in person. Someday. And we’ll post no pictures of the event. In the meantime, here are my questions for, and responses from, an artist I respect and am grateful for.

Why graffiti? Why is this the necessary and only artform for our protagonist?

I've always been fascinated with graffiti since b-boying (i.e., breakdancing) was hot. From my first trip to Chicago as a boy to my first trip to New York City as a teenager, I've been mesmerized by the way that graffiti tells stories about its people, its cultures, and its communities in a common visual field, not to mention the unique ways that BIPOC communities are represented but also reimagined in colorful caricatures. After I'd moved from California to Chicago when I was seventeen, I began studying graffiti in my neighborhood (Little Vietnam): they were full of these secret codes (numerical codes, visual codes, esoteric tags) I was dying to understand. During my MFA, I studied culture jamming and became obsessed. The basic idea of culture jamming is graffiti added to a billboard or advertisement that critiques market capitalism, that makes the advertisement self-destruct by using the ad against itself. Culture jamming is a cultural x-ray to viewers, showing them the truth behind the ad. Whether it's the squalid working conditions of factory workers making textiles in sweatshops in a FEZ (free economic zone) in South Asia for a Gap t-shirt, the starvation, anemia, and dangerous weight expectations of the modeling industry in a high-fashion billboard, or the inhumane living conditions, abuse and destructions of animals, the deforestation in the Amazon rainforest, the environmental degradation, and the toxic runoff of animal waste, all of which are part and parcel of factory farming, in each instance culture jamming attempts to sabotage advertisements, hijack their message, and expose the hidden moral, economic, and cultural costs of those products and industries to the public. In that way, I guess you could say that culture jamming is sort of a declaration of war against advertising but also a wake-up call for consumers, many of whom would rather look away. Ever since I started studying it—thanks Naomi Klein—I’ve always appreciated how political, ideologically informed, and culturally incisive culture jamming is. In Amnesia of June Bugs, I wanted culture jamming to be much more normative than it is. Unfortunately, it has mostly died out. Maybe this novel will start a culture jamming renaissance!

Do you have any personal connection to or experience with the art form?

Not personally, but I have been faithfully taking pictures of graffiti in Chicago from 2004-2008, in New York from 2005-2006 when I lived in Bed-Stuy, in Buenos Aires from 2008-2009, and in LA from 2009-2019 because that's one of my things. I've also taken pictures of international graffiti in Hong Kong, Paris, Berlin, Tokyo, Bratislava, Vienna, London, Madrid, among other cities. If you scan my IG feed, you'll see a good amount of graffiti. I like to capture street art before it disappears because lots of graffiti is intentionally ephemeral. One minute it's there and the next something else has taken its place. Our collective memory fades so quickly, but pictures tend to linger in the cultural imagination. Graffiti, like many murals, is street art with an expiration date and in this novel, you can see my fascination for the way that artists see themselves and their own cities, the way they create their own cultural spaces using their own distinct visual vocabularies of reality and their own unique perspectives of graphic narratives. I guess this is why I think of graffiti as a unique narrative modality that locals can use to tell their own stories about themselves to their own people in their own way. That’s powerful shit! And maybe that's one important reason why Winnie, the culture jammer in Amnesia of June Bugs, feels so important to this novel, why his Buddha Maos show up all the time in this book. Even though Winnie is deeply in love with Ginger and would do anything to be with her, that tenderness and devotion he has for her is matched by the intensity and the righteous fury he has for his art (and his frustration with the incessant economic exploitation of capitalism that exploits AAPI workers). Dude is not playing around with love or politics! Interesting aside: when I lived in Chicago, quite a lot of teenagers I met thought I was a graphie (i.e., graffiti artist) because I was a mix of preppy and hip-hop and I went everywhere with my backpack. The backpack, as it turns out, was one of the most important accessories for graphies because they used them to store their spray-paint. So, every time someone asked me if I did graffiti, I became more and more fascinated with it. Truth was, I was just another nerd with a sensitivity to language, music, and love who read novels and wrote bad prose and did my homework at cafés and started smoking.

The story of the novel unfolds during 2012, but it is so much a novel of the current moment. It's a world that seems both on the point of collapse and on the verge of transformation. Which does the author think it is?

I hate the answer I’m going to give you, but I actually think it's both. I think both regionally, nationally, and globally we are are at an inflection point as a species where we are either going to cross the Rubicon and sadly say goodbye to this beautiful planet that we failed to be good stewards of, or we will be forced to make a series of radical decisions over the next decade that will fundamentally change our relationship to this planet and to each other and to the economic systems that we work in. As awful as the pandemic has been (and it's been atrocious for so many people), it's also been a unique opportunity to reimagine and question reality too, which crises give us permission to do uniquely. Questions Americans normally don't ask themselves like, do I actually like my job? Is this how I want to make money? Am I willing to work in these conditions? Am I being paid my worth? Was I ever? Is anyone? Is this horrendous world all that there is? Is there even a point of starting a family when earth is a giant fireball? What's the point of human existence? Why are Americans so goddamn selfish? Is this really the life I want to live? All of these questions have sprung up everywhere and I think that's a good thing. And I feel like in its own way, Amnesia of June Bugs wants readers to know that love, rage, hope, and hopelessness don't cancel each other out. They're part of the emotional counterpoint of being alive in 2022. This world damages us so much of the time, but it doesn't have to be that way. We live in a dysfunctional, violent, greedy, and myopic reality, but we could code reality differently if we really wanted to. In fact, we'll have to if we want to survive and not lose hope. So, Amnesia is both a scathing critique of the damage we cause each other (e.g., racism, sexism, violence, historical amnesia, classism, xenophobia, numbness, dehumanization) but also a love song for the endless beauty of this world and the importance that love can play in protecting, nourishing, and saving ourselves from ourselves. At least, that’s how the story goes.

Why are your characters vegan? Did they emerge that way or was it a point the vegan author wanted to integrate? How do you manage this formally, giving the characters space to develop and surprise you while discovering or even insisting that they share some of your values?

Not all of them are vegan! I’m not even vegan, lol. Ginger and Winnie’s younger sister, Tian-Tian are, but Winnie is a pescatarian, Suzanne is a vegetarian (paneer and daal give her life), and Aziz is an ecotarian, so he'll fucking eat anything that’s locally available, the little food slut. But this is such an interesting question. I definitely have omnivorous characters in other books of mine, but the more I construct characters, the more I need some of them to understand the value in living and eating consciously. That doesn't mean they have to be like me because that shit would get boring fast, but I do want some of my fave characters to have considered the impact that meat eating in the form of factory farming has on the environment because it's environmentally unsustainable and bioethically harder to justify in 2022 unless you raise your own livestock. The reality is, not only are we cutting down hectares of forests to create farmland for livestock (that purify the air and give us a tiny security blanket against global warming) but then there's all the pollution of groundwater, the recombinant bovine growth hormone, the use of grains (which could be used to feed humans directly), the methane emissions, the inhumane living conditions for the animals, the dehumanizing working conditions for workers, and the medical and financial consequences of red meat consumption. It's literally a predictable but avoidable catastrophe. But I don't need—or even want—my characters to be morally perfect in any way because flawed characters are real characters as far as I'm concerned. I do want some of them to embody a spiritual, moral, and bioethical value system in some way that aligns to my own as a (admittedly terrible) Buddhist. I don't care if the shitty characters in my work eat hamburgers because that's what I expect asshole characters to do, to not give a fuck about anyone or anything, but I want some of the main characters to have considered these issues much more deeply, whether or not they eat meat, because those are the type of people I want to center in my fiction. At the same time, I intentionally don't make all of my characters straight-up vegan because vegans can be hella obnoxious and also, veganism can be incredibly ethnocentric, a surefire way of erasing your or another person's cultural, racial, and culinary histories, which are so often embodied in the food they eat. My wife and I are both mixed-race and both 90% vegan and 10% pescatarian, so the instant we got fish back, we felt like we got our families’ cultures back. I'd like to believe that's one reason why Suzanne (the Indian American character in this novel) eats dairy and why Winnie (the Chinese American character) eats fish, and Aziz (the Moroccan French character) eats lit everything is because these flexible eating strategies allow them to eat so much of the food connected to their own histories, identities, and cultures. Last thing, most of my characters do end up making some big choices for themselves that I didn't predict, want, or intend, and I'm cool with that. Once I have a strong idea of who they are, I usually let them decide for themselves what they end up doing. Not every decision, mind you, but some of their biggest decisions were their decisions and I felt like they just made more sense than what I'd planned for them.

This book includes a few of the most unbearably beautiful, heart-breaking love stories I have ever read. And that's saying something. How do you tell a love story? If you had a 10-step process—like a recipe—what are the necessary ingredients?

That’s such a huge compliment! I'm trying not to cry right now, but it's kinda hard not to! Thank you so much for saying that. That really means the world to me. Tragically, I have no idea. I really don't. Mostly, I just focus on the humanity of my characters first and foremost and then let them kinda take it from there. Because I do give them leeway with their own decisions and because I value and fight for their humanity, above all else, I feel like the love that's sparked between them mostly happens organically. What’s interesting is that in Amnesia of June Bugs, half of the love is counterfactual (i.e., it doesn’t actually happen, but it could have happened under different circumstances) and the other half is real, but comes with tragedy, heartbreak, and disappointment.

The only rules I have for my characters with love stories is that at least one character must be capable and/or willing of falling in love. They might not make great life choices, they might have shitty taste in partners, they might make the same damn mistakes over and over again because human beings, but at least one person must be in a space where they're willing or capable of being vulnerable in some way. Otherwise, love can't happen. It'll just bounce off the characters if they're not in the right place. I think love becomes self-destructive if it’s offered to someone who is not self-aware, courageous, empathetic, and vulnerable enough to value and reciprocate that vulnerability. Interestingly enough, this is also why I don’t believe in falling in love with someone who isn’t ready to fall in love. You can't make someone love you and they won't value your vulnerability either if they're in a bad place. Other than that, I don't have rules for love. I think love defies, contradicts, and resists most rules, whether inside our heads or inside books, so I try not to use them in my life or in my writing.

Your sentences are outrageous. Over and over I'd read one and think/feel: How dare he? How does he get away with this? Tell me about your influences at a sentence level?

Lol, this is like, one of the kindest things anyone has ever told me before. Considering how much I loved and admired Lamb, this is an even bigger compliment than you can imagine. My influences on the sentence level are Joan Didion, Zadie Smith, Junot Díaz, Karen Tei Yamashita, Lydia Davis, Toni Morrison, John D'Agata, Leslie Jamison, Jamaica Kincaid, Kendrick Lamar, Noname, Jay-Z, and Rick Moody. My influences on the conceptual, cinematic, and macrolevel are Wong Kar Wai, early Sofia Coppola, Haruki and Ryu Murakami, Life is Strange, Fallout, Mass Effect (all video games), and movies like Run, Lola Run, City of God, Amélie, Thirty-Two Short Films about Glenn Gould, Coffee & Cigarettes, Les Trois Couleurs trilogy, and Pulp Fiction.

What are you working on now? And why?

Ugh, so many things! In addition to doing PR for Counterfactual Love Stories and Amnesia of June Bugs, which takes up so much time, most of it leading to absolutely nothing because I'm not famous and I don’t have a publicist, I have a choose-your-own-adventure memoir coming out in late July called Dream Pop Origami about mixed-race/hapa identity, AAPI masculinities, love, travel, and metamorphosis, which I'm kinda proud of. Mostly because it took me over ten years to write and rewrite. I'm also working on a couple screenplays. The one I'm most excited about right now is called Mixtape. It's about two mixed-race/AAPI/BIPOC almost-forty-something friends and fiction writers who meet up after ten years in Silverlake. They've had divergent literary careers after graduating from USC where they’d worked with all the writers you and I know from our time there. There’s always been a spark between Misha and Taka that was never explored. Mostly, they just talk and reminisce for ninety minutes, slowly making their way to Venice where they eventually say goodbye.

Beyond that, I'm working on a novel about a family of mixed-race/hapa/AAPI prodigies and a literary fiction trilogy about Addison (formerly, Hidashi) who makes three major life decisions, each decision becoming the premise of one novel. So, in the novel you read, Ninjas of My Greater Self, which is a postmodern novel about racial self-discovery, Addy breaks up with his girlfriend, moves to Japan, and discovers that he's part of an ancient ninja clan. In We Ate Stars for Lunch, Addy stays with his girlfriend and moves with her to Argentina where he realizes that she used him to start her new life without him. He moves back to Chicago where he meets a mixed-race/hapa daughter he didn't know he had from his ex in Argentina. They move to LA to help her acting career where Addy eventually publishes his first novel. And in the third novel, The Light Which Slices Through Me is a Lost Dream, Addy breaks up with his college girlfriend, gets his PhD, abandons his literary career to adjunct, and eventually searches for clues of his best friend who was killed by her partner. This novel will be in epistolary form. Don't hold me to the plot structure in the last two books because I might change them both in a heartbeat, those are just the plot lines I've been considering. So, yeah, I guess I have a lot of shit going on.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but you're not part of the creative writing teaching circuit anymore. What's it like out there in the wild as a poet and fiction writer in an expensive and sometimes unforgiving city? How do you make it work?

Word. After the pandemic hit, LB (my wife) and I kinda re-evaluated all our major life decisions and decided that we were much happier in LA and that living in California for over a decade had irrevocably Californicated us. We didn't fit in the Midwest the way we used to. And we missed our Asian, Black, Latine, queer, and indigenous friends so much. We missed the food! We missed the cafés and restaurants. We missed the style. We missed the beach. We missed the endless flow of creative energy here. I told LB to follow her heart and center her needs. I said I'd figure my shit out eventually. This is me still figuring my shit out, by the way. She wanted to return to LA, so we made that decision together and I decided to leave my tenure track job, so now I'm trying to break into TV writing, trying to get my books optioned by a production studio (I just had lunch with Aimee Bender today where we talked about this very thing!). I'm considering doing some extra work because LA, applying to a bunch of writing jobs that actually pay real money, and oh, also investing in cryptocurrency and the stock market too. I've become such a stock market/crypto geek and I kinda love it. So, I'm considering all of my options right now because money gives you freedom and in my case, money helps me help those I love, which is probably my biggest motivation right now. I'm not sure what my next job will be yet, but I have faith something is gonna work out. I always do. Maybe that's one of my problems.

That said, I've always felt like LA is the best place to live in when you're rich AND poor. When you've got money, it's so easy to drop it like it's hot and there's so many places to drop it, but when you're poor (as all of us were in grad school), many of the best parts of LA were and will always be free: the beach, the blue sky, those 70º days in the spring, those indescribably beautiful drives through picture-perfect weather, the sun pouring into your office window, the bleeding sky after sunset. And for seven bucks, you can get a vanilla oat latte and it will be so damn good. I might be fashion conscious, but so many of my fave things here are free. It is true that LA can be such a tough city to live in because it's fast, rich, dirty, and it seems like everyone is doing it better than you are. At the same time, this might be the only city left in the whole country where it's possible to live off of your art if you make the right connections. You can’t do that shit in New York or Chicago for different reasons. You def can't do it in SF. But LA has a range that I appreciate. There's literally something for everyone here. You just have to find your muse, your mundito, and your medium.