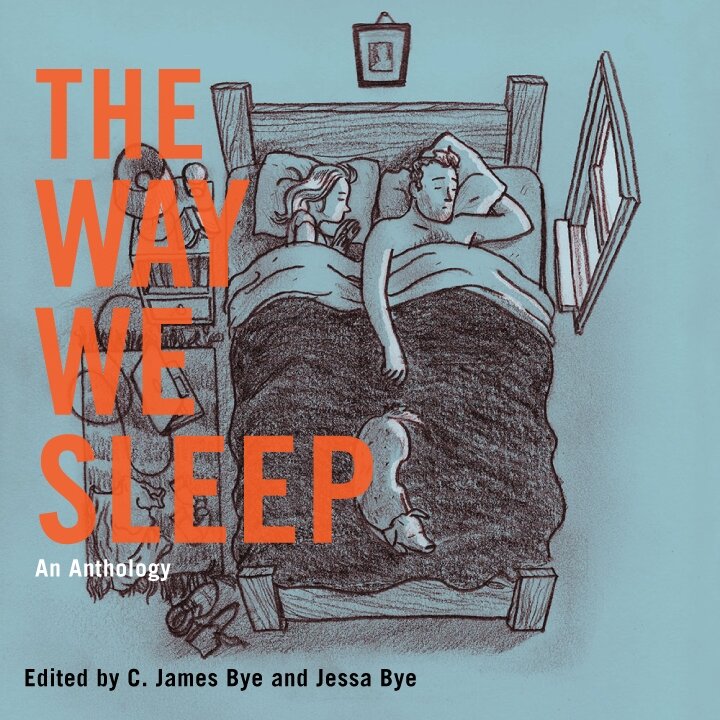

The Way I Sleep Is Sporadically and Often Desperately

The Way We Sleep really covers everything, even the things that haven’t happened to me. It’s beautiful and grotesque and touching and tragic and funny and playful and philosophical and magical.

If you were to see my bed or even my bedroom, it might be hard to think someone sleeps there. Books, paper — so much paper just somehow everywhere — clothes, letters, those envelopes and boxes people mail books in, Gameboy Advance games — only Pokémon, really—a toothbrush, pens, used up batteries, and all kinds of random cords that belong or once belonged to something I needed. The way I sleep is sporadically and often desperately. Somehow, The Way We Sleep captures all of this and so much more.

I don’t like anthologies and have maybe read one or two before picking up Jessa Bye and C. James Bye’s The Way We Sleep. Knowing I had a deadline to read this, I was not looking forward to it. Dreading it, really. Anthologies or even just normal short story collection can take me months upon months to get through and so I was expecting to have to send some disappointing emails this week, explaining I was still only on page 20. But then just three sittings later, it was all over and I was shocked by how quickly it went, how easy it was, how beautiful and painful those pages were.

I have had a very tumultuous relationship with sleep and my bed. Dreams, though, we’ve always been on the same team. But the bed, it can be a lonely place, often a haunted place, a crippling and emotional place. Now, if I were to try to explain what my bed means to me, I’d probably just hand someone The Way We Sleep. It really covers everything, even the things that haven’t happened to me. It’s beautiful and grotesque and touching and tragic and funny and playful and philosophical and magical.

The writing in here is mostly top notch, with my favorites being by Roxane Gay, J.A. Tyler, Etgar Keret, Matthew Salesses, Tim Jones-Yelvington, Margaret Patton Chapman, and Angi Becker Stevens, whose story was my absolute favorite and the one I still cannot stop thinking about. There are a few stories that fall short, but this book is really full of amazing things, and for every story that misses, there are five that hit in ways you never imagined.

And it’s not just full of short stories, but also quick and funny and weirdly insightful interviews and comics. The comics were one of my favorite parts of the reading experience. Right in the middle of the book, it works as a sort of breather from the prose. Playful and funny and emotional, the comics really rejuvenate you and make it so you need to keep reading. For me, even more than that affect is the fact that I dream weirdly often in cartoon. I mean, to see my dreams reflected in a book is one thing, but to see them drawn out is really something else. Something deeply satisfying and beautiful.

The Way We Sleep just works. Maybe it shouldn’t, but it does. Jessa Bye and C James Bye have done a tremendous job here, because editing a book like this is much more than simply checking grammar. The structure and juxtapositions of this book make for an extremely gratifying reading experience and allows the pacing to never get bogged down by similarity of content or tone or style. This is a collection of stories, comics, and interviews that just speeds by.

Being released just in time for the holidays, I can’t recommend it enough as it would be perfect for friends, lovers, and family. There’s something in here for everyone, whether they’re looking for sex or love or humor or just something to pass these cold wintry nights.

So, yes, The Way We Sleep is something you want to read. But be sure to keep it next to your bed, just in case.

Skinlessness: An Interview with Kim Parko

In times of confusion, it is best to stay in the pocket of a bigger animal. There you can be alive and safe in a confined, dark space. Pick a pocket that is only slightly larger than you are so that you can move around a bit.

In times of confusion, it is best to stay in the pocket of a bigger animal. There you can be alive and safe in a confined, dark space. Pick a pocket that is only slightly larger than you are so that you can move around a bit. Pick an animal that is kind and will not eat its young if its young appear to be sickly. Your confusion might be mistaken for sickliness. When you’re in the pocket, just stay curled up. You might even want to suck your toes. Don’t wear clothes in the pocket; the pocket will serve as your clothes. The pocket will keep you warm in winter and cool in summer. Hopefully the pocket is worn over the animal’s heart. You will hear only the noise of the heart. You don’t want to bring your pocket radio, because all you need is the noise of the heart. If the animal’s heartbeat quickens while you are in the pocket, stay calm. Now that the animal is holding you, she will protect you with her life. If the animal falls to the ground and you notice the pocket growing cold, peek your head out and look carefully around you. Has the danger passed? Are there any other animal pockets for you to crawl into?

—Kim Parko, from Cure All

Megan Alpert: The character in the first part of Cure All was so vivid. As I moved from poem to poem, I felt like I was reading about this person who was unique in her sensitivity to the world. And then later, in the poem “Rapist,” when she finds a way to cure the rapist, rather than running from him, I felt that I was reading about the grown up version of the girl from the first several poems. In the book, when you use the word “I” is it always the same “I” or are you drifting in and out of different characters?

Kim Parko: I think that it’s the same in the sense that I have this sort of central character that’s often at the base of what I’m writing about. But it’s not like I’m thinking “This is Patty and this is what happens to Patty here and then this happens to her later in life.” It’s not that kind of character. It’s interesting, though, what you said about her being extremely sensitive — that’s something that I work with a lot and that’s probably a reflection of my own understanding of being in the world the way I am, that is just naturally coming through this character. And so I think when I put that character, that persona, into extremely difficult or painful situations, it’s a way of grappling with how it feels to be that kind of a person. So the “I” doesn’t necessarily always have to be the same person, it’s more the essence of what that character is running through those personas in a very fundamental way.

MA: The situations you put her in are painful, but she always seems to survive them.

KP: Yeah, I think it’s about trying to show how overwhelming or harsh the world can be if you’re especially sensitive. And that it’s not really a weakness, it’s not about an idea of victim — I mean there’s some sort of power in that sensitivity as well, so that that character can feel a lot and can be overwhelmed and can go through intense emotional states but that at the end, it’s just a rawness of dealing with the world and ultimately being able to survive it. And what that experience brings to one’s perception of the world.

MA: How did the book come together? Were you always writing these pieces as part of a whole work or did you gather together disparate pieces of writing? Did you always know that the book was going to be about cures?

KP: I’ve always been interested in the idea of the body. The body is so easily broken and so vulnerable to the physical world. When I was five, my favorite book was a book of skin disorders and I used to love going through it and looking at the pictures. So I’ve always been fascinated by what can happen to the body and ways that the body can heal.

In terms of the way the book was put together with the interludes of different cures, the interludes were part of the structure I submitted to Joseph Reed at Caketrain. We worked together on some of the organizational scheme and on creating some cohesion with the characters and settings in the individual pieces.

MA: You have an undergraduate degree in fine art and you work at the Institute of American Indian Arts. Has visual art influenced your writing?

KP: Definitely. I’m extremely visual. It’s easy for me to conjure up these worlds and I see them very vividly. Visual art can be frustrating to me because it’s a lot harder for me to create that internal space than it is with the written word. With visual art, I’m much more limited in what I can actually create. When I draw, it’s a similar process to writing in that I usually start with a line or a form or a shape and embellish from there without any preconceived idea of exactly where the piece is going to go. It’s similar to my writing in that it always ends up being a form or a creature or world. But with writing I can create a much larger scope. It can take me hours and hours to draw one of these creature-forms I’ve been working on, whereas my writing is just populated with all these creatures and settings.

MA: I’m thinking of your poem “Push,” where a girl grows green fur on her breasts. There are so many weirdly strong images like that in Cure All. Do you ever start with an image and feel uncertain about whether it should be a poem or an object of art? Do you have to work your way through multiple art forms to find out what something wants to be?

KP: Lately I’ve become much more interested in mixed media performance renderings of the stories that I’m working on. I’ve done some costuming and some performing of the scenes in the manuscript I’ve just finished. So I’m working on how these different modes of expression are interrelated for me and how they might have a much clearer relationship. Through turning my characters into visual art, I gain a stronger understanding of them. So if there’s a character that has some sort of strong physical attribute that you wouldn’t normally see in the “real” world, I have to think how will I translate that, how will I make it into a sculpture or costume or an actual object of art.

MA: In several poems you mention a character or object called The Curtain. Could you talk a little bit about that idea and where it came from?

KP: Something that I work on with my writing is the idea of an all-powerful being—God or whatever, just the notion of that sort of existence and what it means to my existence. The Curtain is the thing that is obscuring what’s really there, but it also is what’s really there. So it’s both things. It’s the boundary, but it’s also the thing beyond the boundary.

I often grapple with that idea, seeing what is beyond this reality, what is beyond what I can observe or see. I really like thinking about it. In my newest work I have a character called No One In Particular. People are always asking No One In Particular these questions and No One In Particular is always not answering. But it’s present. Just because it’s been named, it’s there.

Lit Pub Announces 1st Annual Prose Contest!

We are pleased to announce our First Annual Prose Contest, which is now open for entries.

We are pleased to announce our First Annual Prose Contest, which is now open for entries. Submit your best prose manuscript. We’re looking for novels, novellas, memoirs, lyric essays, lyric novels, short story collections, flash fiction or prose poetry collections, and hybrid manuscripts that include prose writing. The deadline to enter is 11:59 PM EST, June 30, 2012.

Judging

Manuscripts will be judged by Lit Pub Books publisher Molly Gaudry and other Lit Pub staff members. Entries will be read blind, and at least one winner will be selected for publication.

About the Judge

Nominated for the 2011 PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award for Poetry, Molly Gaudry is the author of the verse novel, We Take Me Apart, which was the second finalist for the 2011 Asian American Literary Award for Poetry. She has a prose poetry collection due out this fall from YesYes Books, titled Frequencies, which includes companion collections by Bob Hicok and Phillip B. Williams, and she is currently completing a hybrid fairy tale retelling / memoir titled Beauty: An Adoption. In her past two years serving as a Personal Statements Specialist, she has successfully advised 20 applicants competing for national awards, including recipients of 9 Fulbrights, 8 Critical Language Scholarships, 1 Boren Award, 1 Truman Award, and a National Science Foundation Woman of the Year grant.

Guidelines:

Prepare your manuscript as a single Word document or PDF, including a cover page with the title of your manuscript but no identifying information.

Previously-published excerpts or individual pieces are acceptable as part of your entry, but the manuscript as a whole must be unpublished.

The entry fee is $25, payable through our Submissions Manager. When you have paid the entry fee, you will be given access to submit.

You may enter as many times as you like. Each separate entry requires its own entry fee of $25.

Entrant’s name, email address, and other contact information should not appear anywhere on the uploaded file.

Entries may be simultaneous submissions, but the entry fee is nonrefundable if the manuscript is accepted elsewhere. Please notify us immediately to withdraw a manuscript that is accepted for publication elsewhere.

Winners will be announced no later than September 15th, 2012, on The Lit Pub’s website.

Current employees and writers who have a strong personal or professional relationship with the editorial staff are ineligible for consideration or publication. However, past contributors to The Lit Pub’s blog may enter, as all manuscripts will be read blind.

We comply with the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses (CLMP) Code of Ethics.

Contest Code of Ethics

CLMP’s community of independent literary publishers believe that ethical contests serve our shared goal: to connect writers and readers by publishing exceptional writing. Intent to act ethically, clarity of guidelines, and transparency of process form the foundation of an ethical contest. To that end, we agree (1) to conduct our contests as ethically as possible and to address any unethical behavior on the part of our readers, judges, or editors; (2) to provide clear and specific contest guidelines—defining conflict of interest for all parties involved; and (3) to make the mechanics of our selection process available to the public. This Code recognizes that different contest models produce different results, but that each model can be run ethically. We have adopted this Code to reinforce our integrity and dedication as a publishing community and to ensure that our contests contribute to a vibrant literary heritage.

Questions?

Contact thelitpub@thelitpub.com.

David Wallace Disappears 100 Pages In: A Review of DFW's The Pale King

People die, even when they are in the middle of something important. And not only did David Foster Wallace write himself out of his own life, he wrote himself out of The Pale King, his last unfinished novel.

““David was a perfectionist of the highest order, and there is no question that The Pale King would be vastly different had he survived to finish it.””

People die, even when they are in the middle of something important. And not only did David Foster Wallace write himself out of his own life, he wrote himself out of The Pale King, his last unfinished novel. David Wallace himself appears as a character in the densely populated IRS Center in Peoria where the majority of the book takes place, but David Wallace the writer had no intention of seeing his own story through to the end. Pages of his notes accompany The Pale King, and I found this one to be the most haunting: David Wallace disappears 100 pages in.

I’m not the type of person who is affected by the death of public figures. I understand that no one is exempt, no matter how talented that person may or may not be. But I was sitting in a cubicle at a dead end job, decrying my lack of writing time and my slow ascent up the slip’n’slide of success when his death appeared as a blip on the Internet. I hit the denial phase first and plugged his name into every search engine. Then I got pissed. How could someone so talented give up like that? How could he be so selfish? That’s when I shut down. I stopped working, put my head on my desk and breathed shallowly into the crook of my arm. I didn’t cry. Honestly. I just needed a minute to reassess. He and I had grown close as I read through his books and short stories and essays. Infinite Jest, in particular, had seen me through an extended bout of unemployment. These embarrassing emotions happened over the course of maybe three minutes and in plain view of my co-workers. Turns out I wasn’t sad, though. I was extremely disappointed.

I waited to read The Pale King. Part of me was going on about how busy I was, and I didn’t have time for a 600-page book. But in reality, I didn’t want to be done. When I put this book down, there wasn’t going to be another. So I didn’t even buy it. I kept looking at it in the bookstore, pulling it up online, reading a few reviews. It wasn’t until the paperback was released that I desperately searched for a first edition hardcopy that I would have gotten if I’d just bought the damn book when it came out in the first place. Sorry everyone, I got it on Amazon.

First I read the editor’s note by Michael Pietsch. Then I read it again. Then again. I read that handful of pages six times before I even looked at the first chapter. I made my wife listen as I read excerpts of Pietsch’s account of assembling The Pale King from all those finished and unfinished pages. All those notes.

The book feels fragmented as a result. I’m confident that you could pick up The Pale King and read any chapter and it would stand alone. In fact, a few of my friends actually read it that way. There is some overlapping and some chapters give backgrounds into later characters, but it’s very much like a series of vignettes with no resolution. The emphasis on no resolution.

The most surprising element is the warmth of the book. There is a real affection, a gentle touch. Gone was the aloof wise-cracker who wrote The Broom of the System. This was a mature, caring creator of real people, even if they still found themselves in ludicrous situations and possessed unworldly abilities. I’ve heard this book described as an exploration of boredom, but I found the book to be alive in a way I hadn’t seen from him before. It was full of insight into human nature. Many times I found myself nodding along when Wallace got something exactly right.

Like this:

“The next suitable person you’re in light conversation with, you stop suddenly in the middle of the conversation and look at the person closely and say, ‘What’s wrong?’ You say it in a concerned way. He’ll say, ‘What do you mean?’ You say, ‘Something’s wrong. I can tell. What is it?’ And he’ll look stunned and say, ‘How did you know?’ He doesn’t realize something’s always wrong, with everybody. Often more than one thing. He doesn’t know everybody’s always going around all the time with something wrong and believing they’re exerting great willpower and control to keep other people, for whom they think nothing’s ever wrong, from seeing it.”

Wallace spends pages describing the traffic patterns in front of the IRS center and the “me first” culture of driving. Entire chapters are devoted to what characters do to stave off the tedium of looking at tax returns. One character in particular is so detached from the repetitive nature of the job that he is visited by the ghost of a previous employee. Another concentrates so intently that he levitates in his chair. In a section that also appeared in the New Yorker, we learn that one of the men spent the majority of his childhood attempting to kiss every inch of his body. Which of course, took a lot of dedication and concentrated thought. If you like all of your questions answered, this would not be the book for you. But if you’re looking for a meditative look at the redundant minutiae of life, then look no further. We all experience the tedium of the workplace and the small horrors of our advanced society, but no one can portray it more hilariously or with more generosity than David Foster Wallace.

I’m the first to admit that not everything works here. Namely the chapters that are almost exclusively dialogue with no indication as to who is talking. But I truly believe if you’ve never read Wallace before, this is the place to start. Or if you read his previous stuff and he left you cold, give The Pale King a shot. It doesn’t matter if you can keep everyone straight or remember how one person relates to another. It’s worth the price of admission to read the David Wallace chapters, where he interjects as the author to talk about his own (totally bogus) experiences at the IRS center. The bureaucratic foul-ups that propel his first day are some of the funniest stuff I’ve read in years. But I work in an office. I think the first chapter of Something Happened by Joseph Heller is a laugh riot. If I even think about the hacked emails that are sent out in Then We Came to the End by Joshua Ferris I giggle uncontrollably. The really fun thing about The Pale King is that if you don’t like the chapter you’re on, you’ll probably love the one coming up.

And then it’s over.

Life doesn’t treat you. People do.

This volume alone unites scores of extraordinary voices: John Haskell, Dorthe Nors, Sarah Manguso, Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts, Adrienne Rich, Tomaz Salamun, Karen Volkman, Kiki Delancey, Yiyun Li, Peter Orner — honestly, the list goes on. The text on each page was clean and bold, the photo essay by Noemie Goudal utterly haunting.

I am a baby Brooklynite, twenty-four years old and brand new to this strange and beautiful borough. A native New Yorker by birth, I long resisted the desire to actually live and work and perform the acts of adulthood here; of course, I was born fifty miles from the limits of Kings County, in a town that still feels worlds away from my humble apartment on Bedford Avenue.

To assuage the overwhelm of suddenly residing in such an intensely frenetic place (after spending my collegiate years in rural oblivion), I spend plenty of time in bookstores. Even more than the local public libraries, bookstores tend to command a calmness that is nearly impossible to find elsewhere. Brooklyn booksellers usually won’t even bother asking if you need help — they know a dreamy, congenital browser when they see one. (If you do happen to require assistance, however, these well-positioned bibliophiles will provide ample support.)

On an inhospitably warm afternoon last spring, I took refuge in Fort Greene’s Greenlight Books, and after lingering for an obscenely long time, I found the book that would send me directly to the register, currency in hand, and back out into the thick brace of too-soon summer all the way home, where I could be alone and engrossed. The book was not a novel, or memoir, a collection of poems or a cookbook. It was a handsome little literary magazine called A Public Space, Issue 12. This volume alone unites scores of extraordinary voices: John Haskell, Dorthe Nors, Sarah Manguso, Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts, Adrienne Rich, Tomaz Salamun, Karen Volkman, Kiki Delancey, Yiyun Li, Peter Orner — honestly, the list goes on. The text on each page was clean and bold, the photo essay by Noemie Goudal utterly haunting.

As fortune would have it, Issue 12 was just giving way to Issue 13, which I obtained from BookCourt in Cobble Hill, another point on Brooklyn’s literary axis. On the backside of the jacket, a sentence from newcomer Miroslav Penkov’s story “The Letter” was quoted:

“How’s life treating you? she says in exactly those words. Life treating you. . . . A stupider question was never asked. Life doesn’t treat you. People do.”

This was the story I read first, only after returning to devour the “If You See Something, Say Something” section, which included a short essay by Amy Leach and a musing by Leslie Jamison, two authors I have grown to adore and champion over the past year. And after “IYSS,SS,” it was on to more brilliant fiction, essays, poetry, and a very powerful “Illustrated Guide” by Nora Krug.

But it was Miroslav’s story, his first ever to appear in print, that caused me to feel some irrevocable connection to the publication, some mad hunger for an intimate understanding of its mission.

A Public Space met me at the very moment I was quite literally trying to escape the chaos of the street: the bustle, the jostling, the crosswalks, the horns, the sirens, the subway grates, the warm trash, the incessant onslaught of objects and images. And yet by engaging with the work A Public Space had chosen to put into the world, I found myself making more room for the possibilities of the everyday. What might happen, I began wondering, if I paid more attention? If I eavesdropped more closely? If I peered into shop windows I had always bustled by? If I allowed those extra five minutes en route from A to B to chat with a street vendor, a bodega cashier, a transit worker, a fellow walker?

It’s a profound and unexpected effect for a magazine to have, and whenever I recommend the publication to friends, family, and perfect strangers, I even have trouble calling it a magazine, and that’s with all due respect to magazines; it’s simply that A Public Space is actually a mighty river that coaxes many tributaries, and trusts that together these streams will help create a more complete, more complicated, more lustrous representation of human experience.

A month or so after my first encounter, after mercilessly inquiring all over town regarding back issues of A Public Space, I happened to walk right past the magazine’s offices in Boerum Hill:

1. A Public Space

So read the placard on the stately carriage house just off 3rd Avenue. Such is the beauty of living in a place where possibility is as plentiful as pigeons.

In the frenzy of delight that carried me through the rest of that day, I sent an email to the magazine’s general inquiries account and inquired after an internship, which I was granted for the autumn of 2011. After four months of happily, passionately performing my intern duties, I was invited to join the magazine’s staff as the Events & Outreach Coordinator. I know I was officially hired on January 11, 2012, because I have it marked on my calendar: APS: best day of my life. And although I am prone to exaggeration, to a great extent that is the whole truth: it was the day I recognized myself as a little tugboat that had found a worthy river, a path through the wild of an uncertain and young life, which I had chosen to spend (at least for as long as I can manage) in an unforgiving yet magnetic and invigorating place. And yes, I am biased, but you will be, too, once you read it.

This is not a case of mistaken identity. It really is as good as it looks. It is as weighty and textured as it feels. It is as vast and as intimate as it sounds. And it is courageous and elemental, as are the people who sustain it, and the people who put their words and pictures in it, and the people who subscribe and buy and pore over it in the aisles of independent bookstores. Go now, with purpose, and find it.

A Place that Feels Divorced from a Sense of Home

Cityscapes, curated and edited by Jacob Steinberg, is an ambitious project. It aims to gain the perspective of an impressive amount of writers located in major cites not only in the US but around the world.

Cityscapes, curated and edited by Jacob Steinberg, is an ambitious project. It aims to gain the perspective of an impressive amount of writers located in major cites not only in the US but around the world. I know that Jacob has lived in various places throughout his life and has recently made the transition from New York to Argentina. I feel like this contextualizes the project as a subject of not only intrigue but of personal importance. I believe that identity and place are inextricably linked and form almost a feedback loop unto each other. Place shapes identity and identity shapes your perception of your surroundings.

Within the context of new media and the Internet I feel as if one can adopt an almost global identity and feel connected to places and ideas that are divorced from one’s current surroundings. For example, a specific style has formed around new ideas of what literature is and what it can become. Some have called this culture ‘alt lit’ and others feel aversion to that moniker. Jacob’s project was originally titled ‘alt lit cityscapes’ but in the process of working with the diverse styles and viewpoints of contributors it was simply called ‘cityscapes’ in the end. However, whatever one wants to call the online literature scene there are discernable patterns of a homogenous viewpoint. Many writers in this ‘community’ experience similar feelings of alienation from their ‘irl’ surroundings and have sought out the Internet as their surrogate ‘cityscape.’

In Mira Gonzalez’s piece, ‘palm trees are not native to los angeles’ I feel as if she explores the disconnect between her city and her person, in terms of spatial relationship between herself, both internally and literally, in her external surroundings. Taking the title as a metaphor I feel like it expresses her alienation from Los Angeles. The feeling of being ‘out of place’ even though, if I recall correctly, she is a Los Angeles native. I feel like this piece really speaks to the alienation one can feel when confronted with the vastness of everything compared to one’s minor role within it. Mira writes:

lying on the sidewalk

on venice boulevard

i am able to perceive this

inconceivably large distance

between myself and the streeti am trying to become

two squares of cementi am one fraction of the pacific ocean

compared to me everything is enormous. . .

i am one unit of matter

moving through time

at this incredible pace

I like the imagery that is created in this poem. I imagine Mira lying on the sidewalk, almost comically, as other people that are also ‘moving through time at this incredible pace’ pass her by. I Imagine her trying to desperately feel a connection to her city, a connection to anything. Physically she is as close as she can be to her city, trying to join with the concrete, but she is not able to feel a connection mentally. She is somewhere far away. The poem then shifts. Because she feels unable to connect internally with her city she focuses on external, tangible, and objective things. ‘It is going to be 73 degrees today’ she writes without any implication of how she feels about that fact. It is just fact about her city, disconnected from any emotion of affection towards it.

In Megan Lent’s short story she expresses a different perception of Los Angeles. I really like the contrast between her piece and Mira’s piece. I feel like it highlights the subjectivity of experience and how your surroundings can either feel alienating or comforting or sometimes both. Megan expresses nostalgia for Los Angeles that is connected to memories and experiences that have been positive and also influential in the construction of self. She writes about ‘the best parts of Los Angeles’ through short vignettes that make up her perception of Los Angeles.

. . .[T]he ocean. The sky above it. The end of historic Route 66” sign. A blind man playing saxophone. Your best friend standing under the pier. Someone you love walking down the sand with you late at night… A painting that is all in shades of red that looks just like your hair and probably your heart… [A]nd you recognize that you are here, in this city, under this layer of smog, and stars, yes, you are here.

I enjoyed M. Kitchell’s contribution to this project. His piece is a series of webcam photos taken in ‘every place i’ve lived in since moving to san francisco a year ago.’ If I am discerning this correctly, I believe that this piece is showing different living situations within San Francisco. I liked how it shows the transient nature of trying to establish yourself in a new and unfamiliar place.

I particularly liked how Carolyn DeCarlo’s piece, much like Megan Lent’s, focused on not how the specific geography defines a place but how personal experiences and interactions with the people that you meet within the place are what shapes your perception of the city. She writes about the context of place in relation to a certain experience that she had while in a particular place. My favorite lines are

What I’ll miss is

your mouth full of donut

on a bench in Dupont Circle

The lines seem funny and sentimental and not dependent on place. ‘Dupont Circle’ could easily be replaced with any other location but the affection that Carolyn feels for the moment that occurred on Dupont Circle creates affection for Dupont Circle itself.

I liked Noah Cicero’s poems about living in Korea. I found it interested and felt fascinated while reading about people’s subjective experiences in countries outside the United States. I liked the juxtaposition of the perspectives of writers that were natives of country with writers that were foreign transplants. I like how Noah writes in plain language, directly expressing his negative feelings about moving to a place that feels divorced from a sense of home. Noah writes:

I don’t like Koreans

I’m from Brooklyn

none

of the Korean

girls fuck with meso I write this poem

I like the idea of using poetry as a form of expression to relieve feelings of alienation; To try to relate what is inside your head to the heads of other people. It feels difficult to do that when we are distinct bodies, and it is especially a challenge if there is a language barrier on top of the difficulty of trying to get people to understand what you are feeling.

I like how Noah’s second poem deals with a relatively positive encounter that he had with someone in Korea. I feel like the poem expresses a connection and exchange of ideas that directly affected Noah and his perception:

I tell another foreigner

that I enjoy eating

paris baguette for lunchhe respnds

that he has been to paris

and paris bagutte

doesn’t match the power of

french bread. . .

I believed in the purity of his words

I never went to paris baguette again

I’ve noticed these same sentiments being expressed in many different pieces throughout the publication. I like that people feel that human connection [or lack thereof] is what makes something seem good or bad to them.

This is a ‘long-ass’ publication at 290 pages and ideally I would like to discuss every piece in depth because they each feel special, personal, and different, perspective-wise. However, I feel like a ‘long-ass’ review would gradually lose the attention of you, the reader, and consist of me repeating myself a lot.

I highly recommend reading through the Cityscapes collection in its entirety. Overall, I would say that one of the most valuable things that I have gained from reading this publication is reflection on my own city and how I relate to it. I live in Woodbridge, VA, which is basically a city that people pass by to go to DC or Baltimore or any place other than Woodbridge, VA. I don’t feel a strong affinity for my city but since my external world is lacking in the things that I would want from a city I feel like I have immersed myself in a wonderful online community that I would consider my true ‘cityscape.’ There are many people in this issue that I have interacted with formed connections with online that feel just as dear to me as any ‘real life’ interaction. In my opinion, a conception of place has less to do with specific geography and more to do with the people that you chose to interact with. Anything and any place can become your city, regardless of physical location.

Things that are Unanswerable; Moments that are Unpackagable: Tom Noyes's Spooky Action at a Distance

In his wonderful second story collection, Spooky Action at a Distance, Tom Noyes continues to explore the mysteries that surround us that we so often take for granted: faith, grace, and the irresistible urge to do things we know are not good for us.

In his wonderful second story collection, Spooky Action at a Distance, Tom Noyes continues to explore the mysteries that surround us that we so often take for granted: faith, grace, and the irresistible urge to do things we know are not good for us.

In the brief but affecting “The Daredevil’s Wife,” the protagonist decides to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel. It’s a stunt he comes to almost haphazardly, ultimately choosing the barrel over crossing the Falls via tightrope because the former requires no skill: “This is the physics of the barrel: curl into a ball and hope. This is the geometry of Niagara: down.” His wife, anxious and afraid, asks him why: “Asks him over and over. But the daredevil has no answer.” He simply knows he has to, which strikes me as such a perfectly sad and human urge. The desire to do things that may hurt the oneswe love, and in the end leave us or them alone in the end. But we do them anyway.

In an interview with Scott Phillips, Dan Chaon (another author whose work I love) claims he himself is “not too interested in the idea of Truth, or even of ‘epiphany’ in fiction,” but rather “things that are unanswerable . . . those moments that are unpackagable.”

What could be more unanswerable than the kind of self-sabotage we catch ourselves practicing, the kind that injures those we care about the most, lying or hiding or putting our hearts’ deepest longings before theirs?

As he floats toward the roar of the Falls, the daredevil hears his wife singing and for the first time doubt consumes him, not at the choice he’s made but at what her singing might indicate. It’s a brilliant ending to a beautiful story in a book that’s full of them.