Beasts of the Earth: A Camouflage of Specimens and Garments by Jennifer Militello

In 1927, twelve-year-old Marion Parker was abducted from her school in California, held for ransom, and then killed and gruesomely mutilated by a man named William Hickman. He slit her throat, cut off her arms and legs, cut open her abdomen, removed her organs, stuffed her body cavity with rags, and used wire to sew her eyes open. In short: horrifying.

In 1927, twelve-year-old Marion Parker was abducted from her school in California, held for ransom, and then killed and gruesomely mutilated by a man named William Hickman. He slit her throat, cut off her arms and legs, cut open her abdomen, removed her organs, stuffed her body cavity with rags, and used wire to sew her eyes open.

In short: horrifying.

And in the well-trod tradition of sensational journalism, it horrified the nation in a sweeping national obsession. Hickman was the human monster — the beast — whose combination of charm and violent, aberrant psychology fascinated and titillated. Parker was the picture of girlish innocence — here brutalized by masculinity, perversion, and modernity. Marion, and her murder became a metaphor and canvas onto which a myriad of anxieties could be, and were, projected. Volumes of newspaper articles, folk songs, and even a partial novel manuscript have been written about the incident.

Jennifer Militello, in A Camouflage of Specimens and Garments, unearths the events in poetry — or, actually, it is more accurate to say that she unearths Marion Parker, and tries to give the girl some measure of voice and subjectivity stripped from her first by her murder, and second by her canonization in the media. The result is raw and devastating.

It’s not until roughly the midway point of this powerful collection that Marion Parker speaks to us — on the topic of her murder and mythos, no less — directly. However, once she does, it’s clear we have been circling this story and the companion themes throughout. It’s also at that point clear that the speaker in the epistolary free verse pieces which encircle the three main cycles of poems in the collection is Marion — or a distillation of her or all of the many, many girls like her. And that’s how this collection operates: by dawning understanding. Each new poem reaches back and changes the way you had read the ones which came before, which changes the way you are reading the poem you are reading now, which hints at what may be coming . . . eventually you are left with a fizzing continuity of experience.

The first cycle of poems is all raw and ancient wildness. The most enervating poems use imperfect rhymes and irregular rhyming schemes to build a fast, syncopated beat that gets in the bones. The frequent use of repetition and parallelism at the start of thoughts or lines lends these pieces a flavor of an oral tradition — and thus antiquity. Beasts haunt the verses — haunt the book — including potent archetypes of wolves and werewolves, dogs and hounds, the hunt, the woods, the darkness, and the old gods. Here already, though, Militello is laying track for what is to come. The beasts are not simple monsters, and their female prey not simple victims — that worn old narrative has no place here. In “A Dictionary of Having Been Prey in the Voice of the Grandmother” in which Little Red’s dear nana is freed from the belly of the wolf with the thought, “I could finally be the beast,” and “I had been eaten, I was the beast. I had the taste of bewildered flesh.”

She’s constructing different narratives here: no damsels.

Harder to parse, but marrow-rich is the collapsing of the dichotomy of birth and death. Birth and death are simultaneous and synonymous, as in when in “A Dictionary at the Periphery” the speaker narrates: “On the day I was born, the moon’s phase / was waning crescent. No death / to sweeten like a side dish . . . ” and later, “I was the last animal at the lamp the night / man was born. Record me in the morgue’s lost books.” And in “A Gospel of the Human Condition” we find, “Ourselves / at periphery. Begotten, not made.”

The middle cycle of poems shifts from an animal restlessness to something more modern: chitinous, and uncanny. The poems are full of industrial, scientific, and brutalistic imagery; and the forms of the poems change with the same restlessness. “Corrosion Therapy” opens the cycle with an algebraic equation, in contrast to the mythic language of previous poems, and pulls the reader in to the darkness, inviting us to a crime and to a complicity in beastliness: “You can’t deny your decisions now that / you can smell what we’ve been, our / living, our pride, our cool little eyes / like rainfall that don’t care one bit. / It’s suicide only to one part of you. / The other part connives to come, to kick / the lame dog, to take advantage / of the dark, to test the door to alive. Is / it locked or ajar? How far will it open? / If I fit through, who will die? Say / goodbye.” Notably, in this section the beast is us, and it is modernity, and it is society. Thoughtfully, Militello follows this revelation of our own beastliness with the aptly named “Criminal How-To” — to help get us started on the crooked and wide.

This is where Militello introduces The Sociopath — an archetype as strong and pregnant to modern times, as any beast from the epic sagas of the ancient world — and their voice unsettles from the first moment it appears in “Dictionary of Wooing and Deception in the Voice of the Sociopath.” It’s not a stretch to imagine that The Sociopath is, at least in part, William Hickman; however, The Sociopath is carefully de-identified — we are discussing a type, a mythology, and a whole group of people (men). “Godless, I am most real / Healed, I am / most ill. Filth is my most honest hour,” and later, “I barter with the periphery,” proclaims Militello’s Sociopath, with the precise sort of Nietzschean Superman ideology which drives our fascination with “sociopaths.” But Militello’s Sociopath both is and is not a beast, because he is also a man: in “A Dictionary of What Can Be Learned in the Voice of the Sociopath’s Lover” we hear from a woman who loved him, a woman who is not a monster, or a nihilist, or a pitiable creature. She is complex, and damaged, and strong; there is a desperate, defiant energy to the Lover’ when she calls, “To wreck whatever touched my hand / to prove I still exist.” and, “Not to want.” and, “To fight and spit. To / let it go. To earn my keep.” She is human, and then so to is the Sociopath — a human beast, which is a much more disturbing proposition, from which a lot of narratives turn away.

And then we arrive at Marion Parker.

Her poems are devastating. Here Militello imagines a Marion, first in “A Dictionary of Mechanics, Memory, and Skin in the Voice of Marion Parker”, who laments her lost life: she will now only get to grow old “in the minutes it takes to be dismembered: / one suture for each of my antiseptic mouths. / Tattered is how I began.” She worries: “If I do not happen soon, / I will not happen at all.” Marion continues, in “A Letter to the Coroner in the Voice of Marion Parker”, to cry out: “I am trying not to break. Debris is all I am. / My face gaunt where once it was seamless, entrails / replaced by rags, eyelids wired open, a congregation / in my eyes with all the candles held by children.” These poems more directly deal in the violence visited upon Marion.

Then comes a different Marion, who — remember — is imagined in these poems as speaking from beyond the grave, in the poem “A Dictionary of Keeping Quiet between the Monstrous and Holy in the Voice of Marion Parker.” She moves from discussing her death, to the creation of the Type or Identity of Marion Parker (in the media and public discourse): “I cannot be made / natural since my flesh / burns with these machines. / I am crafted of dimensions, mathematical, a prize. / I am somewhat alive.” She says: “There is not rest for / the wicked. There is no / remembering the grand. / I take the hands that hurt me and mistake them / for my hands.” She grows angry at this second violence, the flattening and constructing of her identity: “The hour is anger, is artifact, is over.” declares the speaker of “Working with the Instruments”, repeatedly delivering the imperative “kill it.”

The third and final poem cycle brings us to the present day with “A Dictionary at the Turn of the Millennium”, which greets our era with a series of “hellos” to the various ills of our society, from overcrowding, to experimentation, from hopelessness to “adrenaline catastrophe.” The cycle pivots to “A Dictionary of Resignation,” elucidating the inevitable coming apocalypses: “Enough. The dogs of god are loose. / Finally the nights you do not sleep / like packs outrun the wolves,” and, “Touch is a rough crypt of covenants. / Random things awake. / Draft horses cart their owners to the grave. / The inept shall inherit the earth.” Decline and decay are a theme throughout the section, but the myth cycles also return: to start with: Icarus and Odysseus make appearances. And their stories are not relayed so much as reframed — Icarus is a figure of hope not hubris, Odysseus’s story is one of unarchaic homesickness.

The wheel turns. Endings are beginnings. Birth is death.

In “A Dictionary of the Dead in the Voice of the Living Collective” the dead (the past) literally live inside of all of us: “They think of flame but sing of ash, a drop / of this, a sip of that, their lairs inside us / skinned and mute. Eyes a snapshot of hunger.” Nothing is new, and the wheel turns. In this way, the final poems are an affirmation and release: everything is terrible, and an End is coming — whether simply death for the individual, or a societal collapse — but an end of one era or cycle is simply the beginning of another. Near the very end, Militello moves to using a chilling, powerful “I” as the narrator — a collective voice of humanity? Or the dead? — who tells us in “A Dictionary of the Afterlife” that a beast approaches to devour the earth and “digest the bones to break them.” But this “I” will bury the beast, drown it in a fountain. It’s a powerful final chord.

On the Authority and Surrender of Writing a Novel: A Conversation with Laura Catherine Brown

Laura Catherine Brown is the author of two novels: Quickening (Random House, 2000), which was featured in Barnes & Noble’s Discover Great New Writers series, and Made by Mary (C&R Press, Spring 2018).

Laura Catherine Brown is the author of two novels: Quickening (Random House, 2000), which was featured in Barnes & Noble’s Discover Great New Writers series, and Made by Mary (C&R Press, Spring 2018). Laura has taught writing at Manhattanville College, and her short stories have appeared in Monkey Bicycle, Tin House, and Paragraphiti, among others. She has attended residencies at Byrdcliffe, Djerassi, Millay Colony, Ragdale, Ucross, Vermont Studio Center, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and Laura credits these residencies with allowing her the opportunity to complete her novels. Laura currently lives in New York City with her husband. She is writing her third novel.

Marni and Laura bridged the gap between Maine and New York City with a conversation that included Laura’s struggles and triumphs while writing Made by Mary, how she adds humor to gloom by putting the “fun” back in funeral, and finding a novel’s “secret center.”

*

MB: I noticed you taught at Manhattanville College for two years. How do you find your writing life cohabiting with teaching writing?

LB: I loved teaching. I loved seeing students’ work evolve. I loved the classroom discussions and the vibe of Manhattanville. It was good for my writing life to be part of the community, to read and analyze stories and to talk about craft. The student work was almost always courageous. I had to constantly remind myself to heed my own advice about taking risks and overriding the inner critic. Self-criticism and perfectionism never fail to annihilate freshness in the work, and this was particularly obvious to me when I was teaching undergrads in creative writing and seeing how hard on themselves they were. But while I was teaching I was also working as a graphic designer, which made finding the time to write almost impossible.

MB: How does your graphic design work feed into your writing?

LB: I’m a visual person. I went to art school where I studied graphic design, and I’ve earned a living as a designer ever since.

As a designer, words are not my medium—it’s color, shape, layout, typography, concept. Most graphic designers I know are avid readers, so there’s crossover, in terms of literary interests.

Graphic design is collaborative, client-based and deadline-driven. Writing is solitary and can feel open-ended, so the two pursuits provide a nice balance.

I love designing book covers and book interiors, but I make my living doing mostly corporate design. In fact, I designed the cover and the interior of Made by Mary, which was a lot of fun. In terms of imagery in my written work, I think I’m always “seeing” my imaginary worlds and characters before any of the other senses kick in.

MB: I love that you designed your book’s cover. Circling back to teaching—because I know you teach yoga—I once had an advisor for teaching writing who said she simply couldn’t write on the days she taught because, and I’m paraphrasing, “As a teacher, I can’t be as stupid as I need to be as a writer.” I took that to mean: As a teacher she needed to have a sense of authority; whereas as a writer, she needed that authority to break down, so she could discover a story. Do you feel like you need to have a sense of authority, during your writing process?

LB: This is such an interesting question. I think it’s true that you need to be stupid and sensory, and free yourself from conceptualizing and analysis. Yet, authority seems necessary to me, in order to claim permission to tell the story. One of the people who read an early draft of Made by Mary described it as “mushy.” I interpreted this to mean it lacked a story-telling authority, and thus it lacked cohesion.

In life, you can’t stay on the sidelines. You have to take a stand. The same is true in writing. I needed as an author/narrator to state unequivocally: “This matters. Here’s why.” But I kept churning out scene after scene, somehow believing “the mattering” would reveal itself without my having to stake a claim and that if I just kept exploring stuff, the “story” would arise from the scenes.

If I’m brutally honest, I may have been living my life like that, too—with a passivity I rationalized, since so much seems beyond my control. I’ve learned that it’s important to set intentions, even if life presents obstacles, and even if intentions are not met. They can change, but it’s good to have a lodestar.

MB: What an insight—that your writing life can parallel your actual life, and authority in writing can lead to authority in life. I’d love to talk a bit more about that. What are some particular passages in Made By Mary that you recall really requiring your authority more than others?

LB: I think the Wiccan ritual scenes required giving myself permission to write, despite my fear that I didn’t know enough about Wicca. Fear is a great tool for abdicating responsibility and authority. I’ll never know enough about anything! Also, in general, I took many writing workshops because I desperately wanted someone to tell me how to shape my narrative, which seems crazy, but I was having so much trouble figuring it out on my own, so I hoped an “expert” could help. No one else can shape your narrative except you, the writer, the ultimate arbiter.

MB: What did you do to assert your authority in those passages?

LB: I barreled through the ritual scenes and revised endlessly. But I asserted the crucial authority when I finally completed a full draft. This took me a long time because I kept circling back to revise the beginning, getting lost in loops and tangents of self-doubt. Forcing a narrative forward, not knowing whether you’re leading to a dead end or a breakthrough, not knowing whether you’ll find gold or just get lost, this is a daunting and arduous and time-consuming task, and requires authority. It’s as if the writer has to be a resolute explorer at the mouth of a dark scary cave, shouting, “I’m going in!” You don’t know what you might find, you don’t know if it’ll be any good, but you have to go in and write it anyway.

MB: How did this authority in writing these scenes parallel authority you found in specific areas of your life?

LB: I think I’ve had trouble asserting my wants and desires, even to myself. I circle, I evade, I deny, I avoid. But writing the passages where all the characters are engaged in Wiccan rituals and, as the writer, inhabiting their desires and motives, freed me. Writing allowed me to recognize my own yearning, along with a wider recognition that we all have ongoing desires and agendas—it’s human. Above all, I wanted to finish the book and have it be the best book I could write, knowing it would be imperfect, and putting it out there anyway. Therapy helped a lot, too.

MB: In your website bio, there’s an interesting line: “Laura sees a common thread among the three pursuits that she’s most passionate about: writing, yoga and graphic design all require practice, dedication and constant, ongoing surrender.” I can imagine that common thread. But I’d love it if you wouldn’t mind elaborating on this idea of “constant surrender,” because I think I require it too as a writer. I’d love to know a little more about how “constant surrender” feeds into your writing process.

LB: There’s a yoga concept called “effortless effort” that I think applies to any creative or spiritual endeavor, or just life in general, no matter what you’re doing. For instance, in meditation or yoga, you have to show up on the cushion or mat—that’s your essential obligation. You strive for mastery, while simultaneously you have to accept fully where you are. I think writing and design are conceptually similar to yoga. They’re process-oriented and experiential, full of play and possibility. They have recognized forms (with infinite and ever-evolving variations). And we aspire toward mastery while having to accept where we are.

It’s paradoxical. Something is bound to happen, but it’s not entirely under your control, because the creative process simply isn’t controllable. That’s where the surrender comes in.

MB: What were some areas of Made by Mary that required surrender—were any curiously the same passages that required authority?

LB: The areas that required surrender were definitely connected to the areas that required authority, and they relate to the Wicca aspect. I knew from the start that these characters believed in a Goddess-centered animism. But at a certain point in the process, I realized that their belief system could not operate merely as a backdrop or group identity, it had to generate narrative movement and become much more real. In other words, magic had to happen. I resisted this for a long time. It felt like so much work! I didn’t know enough! Also, I had never intended to write a “supernatural novel.” But I surrendered because it became a narrative imperative.

MB: If a book were related to a child, growing, it seems the parent/writer would need to somehow be able to wield both authority and surrender with someone/something that has a will of its own but still needs guidance. Is this analogy a stretch?

LB: Not a stretch at all! I think you have to let the work surprise you, and you have to venture into the unknown, or it’s boring. Likewise, you have to allow your child to not be you, and to not be limited by who you think they are, or who you might want them to be. They are themselves, but you still have to usher them into the world.

MB: Made by Mary begins with an immediate sense of loss. The reader discovers quickly that the character “Ann” can’t have a child—and perhaps cannot adopt. Many stories stem from a problem that needs to be solved, of course, but can you talk a little bit about what inspired this work?

LB: The book arose from a story I’d read in a newspaper while waiting in line at the supermarket about a woman who gave birth to her own grandchild because her daughter didn’t have a uterus. It was a bare-bones tiny article that caught my eye, and I immediately began to fantasize: How would it feel for a daughter to need her mother in this way? And what if her mother was a dominating person? How would the father of that baby respond to the situation? I imagined this mother feeling like a goddess bestowing a gift. And the character of Mary appeared before me, fully formed. It was imperative that Ann exhaust all other options, otherwise she would never have agreed to the arrangement. Ann had to be at the end of her tether. But that plot rationale came later.

MB: Made by Mary has a strong comedic thread. I’m thinking of the character “Mary” with a smile on my face. She appears as a kind of New Age enthusiast who, though loving, is initially suspicious of her daughter’s desire for a child. There are so many ways to write about loss—and many leave out humor entirely; I’m thinking of Sylvia Plath on one end of the “serious” spectrum. How did you come to decide to add lightness to what could be considered an otherwise painful journey for a character trying and failing to have a child?

LB: I try to approach everything with humor. The saddest situations can sometimes give rise to the most hysterical hilarity. The line between laughing and crying can be porous.

Here’s a real-life example: Someone brought a dog to my father’s memorial, which was held in a small theater. And the dog trotted up onto the stage and took a shit while everyone was singing Amazing Grace. That was so funny we literally bent over in pain laughing so hard. But it was also very sad, because my father had died. We put the “fun” back in funeral. I think life is full of situations like this.

MB: Did any of your life experiences inspire Made by Mary?

LB: One of the challenges of [writing Made by Mary] was how invented it was, especially compared to my first novel, which I culled from my life. I realize I’m someone who needs to bring my life somehow into my fiction, or the text feels dead, like an empty exercise. The Catskills setting in Made by Mary is drawn directly from my past. As a teenager, I lived near the town of Bethel where the Woodstock Concert happened. Now, in the present day, there’s a beautiful concert venue there. But when I was in high school, there were empty fields surrounding a defunct dairy farm in a depressed upstate county. I mourned my fate at having been born too late and missed the crazy hippie era.

Also, my husband and I tried to have a child through IVF. It was very expensive and it ultimately failed. Nobody talks about how often it fails. It was many years ago, we’re both fine with being child-free, but those were some tough times.

MB: Was writing Made by Mary a useful way to process this experience in your life?

LB: Only in retrospect. The two processes (IVF, writing a novel) feel similar in that there’s a time-consuming slog toward what you desperately hope for (a pregnancy, a book); and you can ultimately fail at one or both of those endeavors. I’ve come to believe that failure is a good thing. It seems almost cliché to mention Samuel Beckett, but his famous quote from Worstward Ho is brilliant and, in my opinion, brimming with hope and perseverance. “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

MB: Speaking of how reality does or doesn’t feed into your work, do you find the news these days too distracting? Or does it inspire you? Or even both?

LB: The news these days is so much stranger than fiction! Because I’m concerned with “ordinary” people, I have to push aside the endless chaos and drama, which is celebrity-based and reality-tv-star centered. But I also feel the urgency toward political activism and resistance. I don’t want to regret not having acted when I could have and should have. But interior lives matter more than ever, so I drag myself away from the news. I use an app called Self Control that lets me block sites.

MB: Have the residencies you have attended had a similar affect as Self Control—providing some relief from the hustle and bustle of daily life?

LB: I’m not sure I would have been able to complete either of my novels without the incredible gift of artist residencies.

Most residencies provide food, bedroom and a studio to work in, and they host artists of all disciplines (visual, musical, literary). There’s a magical cross-pollination that occurs. The freedom from chores and meal preparation is a blessing and then some. There’s time and space to sit with your work and connect to the “long thought,” which is the quality of knowledge and being that allows for a deepening and an expansion of consciousness. There’s an opening that arises. This simply doesn’t happen in my daily life with its constant tasks and interruptions.

MB: In The Naive and the Sentimental Novelist, Orhan Pamuk writes that all novels each have their own “secret center”—not an actual place, but a central wisdom that a novel imparts; he argues that the act of writing and reading is inspired by the hope in both the writer and the reader to find the secret center. At what point in writing Made by Mary did you notice its secret center? And, without giving too many secrets of the book away, what would you say that secret center is?

LB: I love this concept of the “secret center.” That’s absolutely beautiful! It feels very true. I think I came to know the secret center of Made by Mary early in the process—as having something to do with the way love is passed on from generation to generation, as well as the way emotional wounding is also passed on. In the course of writing the book, I learned to focus more energy on the love and less on the wounding. I think that’s the secret center.

Dean Kostos: Poet of Two Worlds

It can be argued that all poetry is a negotiation between two worlds. An interior, private jumble of imagery and sound, a chaotic montage, must find the proper words to convey meaning to the world. For a poet who has suffered from severe mental trauma, the task of creating balance and harmony in language becomes even more crucial.

It can be argued that all poetry is a negotiation between two worlds. An interior, private jumble of imagery and sound, a chaotic montage, must find the proper words to convey meaning to the world. For a poet who has suffered from severe mental trauma, the task of creating balance and harmony in language becomes even more crucial.

Greek American poet Dean Kostos is one of these damaged negotiators. In his early books his language is playful and inventive; he is adept with forms such as ghazals, but underlying all is an uneasiness with surfaces. The discomfort is made clear in a poem called “Rampart” from his first book The Sentence That Ends With a Comma: “You never realize it, but the/ dust is the world’s gradual crumbling/ as you proceed to speak.” An increasing poignancy enters his work for the residue of lost lives, civilizations, and dreams. This is often reflected in poems that reference both ancient and modern Greek history, language, and art.

His poem “History Tilts across Your Hips,” from Rivering, is addressed to the famous Kritos Boy statue by a narrator who remembers “ravines perilous as love” in his own life and looks into the eyes of the statue with worship. But also, sadly, despair. “When your eyes speak, one talks / of arrivals, the other / of departures, each a tunnel / away, your thoughts unspooling / toward the vanishing point.”

Later on in the poem, a chiton (as remembered clothing) falls, “heart-roots snap/ from muscles memory,” and yet a divisive distance remains in the last lines. “One eye: Leave;/ the other; stay, stay.” Can this be the distance between an ancient past, idealized as more whole, and a contemporary world marked by ambivalence? Or is it an attempt to reconcile the two? As it stands, the poem is a brilliant evocation of the two worlds each lover carries within: the fight between past and present, between avoiding desire or accepting Eros.

Kostos writes about outsiders, but not as an impartial observer. He endured the violent bullying of classmates at his boarding school for being gay, and at one point was thrown down a flight of stairs. At the age of fourteen he entered a mental institution, where he stayed for two years. However as an adult he became a professor respected by his peers, won a Benjamin Saltman award for his poetry, and is the author of eight books.

In his poetic landscapes, figures move about who are damaged and marginal. A dwarf pushing a pram, Coney Island sideshow performers, Miss Havisham from Dickens, Jack and Ennis from Brokeback Mountain, even the Dauphin, the ten year old son of Marie Antoinette who perished in prison, his “mushroom-colored” heart stolen from his corpse. The poems insist that we live in two worlds: the world of commodities, appearances and structures, and another world accessible to those initiated by suffering, then understanding and compassion.

In a poem called “Creature of Two Worlds” from Last Supper of the Senses, there is a metaphor for this suffering, a description of a sycamore tree placed by a fence secured with a padlock.

Despite its growth, the tree can’t bend

to thrust out the obstacle, and so pretendsto need it, burling pulpy meat

over the metal like a punched lip eating.The desire to be freed may not relent,

yet a saw would gut the core to cut the fence.

The preceding lines certainly have a precedent centuries ago in the Romantic movement, however Kostos, as a poet living in an age of deconstruction, creates a dialogue between what he sees as a place where truth springs from wounding, and the often false, commonplace world based on social interactions and shared assumptions.

Because Dean Kostos believes the true heroes of this struggle are outsiders, he gives us a persona poem whose narrator is the ghost of Amadou Diallo, an innocent man murdered by New York City policemen. Kostos makes readers empathize with the wounding of Matthew Shepard, another man murdered, this time for being gay. And mathematician Alan Turing’s life is also celebrated, though his untimely death is mourned. Ashile Gorky, Sylvia Plath, Hart Crane, and Frida Kahlo all appear as guides who hold the key between two worlds.

Most of his poems are also lyrical, with striking imagery. Here is a poignant description of a Coney Island sideshow performer in the beginning lines of “Scorpion Cowboy,” from This is Not a Skyscraper.

How does he tend to the body’s needs?

Clunk! His pincers thud like sand-filled shoes.

Making his mother’s body bleedwhen he was a boy, he swore he’d

mask his thalidomide shame like a bruise.

In a poem called “Turkish Man With Cinnamon Eyes,” also from This Is Not a Skyscraper,the narrator speaks from historical wounds inherited from four hundred years of oppression, when Greece was under Turkish rule.

I say the world is text & we read it.

The world is history & we bleed it.I say, I’m unable to love. Love me.We stand above the bridge, peering down,

the East River rippling below us—

hair of a deity about to breathe.

While a wish for healing may exist, Kostos is too fine a writer to present his readers with New Age homilies about self-acceptance. There may be no conclusive way to bridge a gap between two worlds, despite the clever use of an ampersand or skillful line breaks. “Wounds Wound with Poems” suggests that the creative process itself is a kind of surgery. “Perhaps all poem are bandages,/ pristine or blood-soaked.”

Kostos implies that all of us, whether or not we create art, have “sought approval from monsters who traffic shadows.” It’s fitting that that he mentions a chilling episode from The Twilight Zone television series that involves unwound bandages and approval. And poets themselves hold chisels that are “dark & dripping.” But Dean Kostos is one poet who does so with grace.

We wait in hell’s white-enamel cellar.

Plants shrivel on sills. Our hands

flicker like wings, as computer keysclatter, carving words into luminous

screens. We try to hew our David

from all that he is not—

our chisels dark & dripping.—“Wounds Wound with Poems,” from Pierced by Night-Colored Threads

Nightwolf: An Interview with Willie Davis

Immediately the book excited me, its story, its prose, its damaged and compelling characters; I read it deep into that first night, and the next, and more after that. By the time I finished it, I wanted to talk with Willie about it. Lucky for me, we were able—through the miracle of email—to have that conversation.

Sometimes things come to you unexpectedly, in a plain wrapper with an unfamiliar return address. And the best that can happen when you open these unexpected things is that you make a welcome new discovery, unwrap something that you didn’t even know existed before this very moment. Something exciting, something you are not eager to put down.

That’s the feeling I got when an email from someone I didn’t know showed up in my inbox. I opened it to discover an evocative new novel Nightwolf, by a very engaging writer, Willie Davis. Immediately the book excited me, its story, its prose, its damaged and compelling characters; I read it deep into that first night, and the next, and more after that. By the time I finished it, I wanted to talk with Willie about it. Lucky for me, we were able—through the miracle of email—to have that conversation.

*

Patty McNair: There are quite a few things I’d like to ask you about Nightwolf, but let’s start with the role Lexington plays in the novel. The city serves more like a character than just a backdrop, as some settings might. I have traveled quite a lot, but I have never been to Lexington. It felt wholly unique to me, its seedier parts, its neighborhoods, its inhabitants. Would you talk a little about how you chose Lexington for this story and why? It seems like a choice made not just because you know the city, but because this story could not take place anywhere else.

Willie Davis: My mother lived in Lexington, and my father lived in East Kentucky (the hillbilly, coal-mining part of the state). I grew up bouncing between the two places. Lexington, the urbane college town, called East Kentucky a bunch of stupid rednecks. East Kentucky called Lexington a bunch of pussies. I’d switch accents and agree with whichever set of friends was talking. I left Kentucky when I was eighteen because I couldn’t figure out a way to leave there sooner. If you’d have told me then that they built a moat around the state line of Kentucky I doubt I’d have cared. I pretended I didn’t like country music because I didn’t want to be thought of as a stupid Kentuckian. But, of course, the minute I left, I began to find Kentucky fascinating. In short order, I went from being embarrassed by my accent to playing it up to make girls think I was interesting. I wrote about Kentucky, and through writing, I fell in love with Kentucky, but only at a distance. I wanted to tell the stories of Kentuckians, but I wanted to stay away.

I started writing this book shortly after moving back to Lexington. Suddenly, I love living here. A lot of that is how the city has changed but mostly it’s how I’ve changed. What irritated me about Lexington before now seemed gorgeous to me. I used to call it the middle management of cities, a suburb to nowhere. But, of course, the hillbillies of my youth have moved to Lexington. It’s a city that’s getting constantly reinvented. The rural and the urban mix down here, but not much.

Lexington is a city that has a great deal of joy and shame and anxiety for me. It’s a place I love and is very close to my emotional core. It’s worth noting that the Lexington of my novel is at best a second cousin to the real Lexington, Kentucky. Some of that is practical. I have—this is not an exaggeration—the worst sense of direction of anyone I know. My mind simply has no spatial memory. There’s no way I could keep a map of the real Lexington in my imagination. I fictionalized it so it can react to the characters’ needs. If they need a walkable neighborhood or a reservoir, then Lexington could react to them. In that way, my off-center Lexington could interact with the characters around it.

McNair: Perhaps that is why the city seems so unique to me as a reader; it is both real and not. Like your characters. Milo, for example, is a complex character. When your reader is first introduced to him, Milo is behaving rather badly. He is a tough seventeen year old, engaged in regular illegal and often brutal activities. But he is funny, witty, quick with the one-liners and sharp repartee. And there is a real vulnerability to him as well, despite his yearning that there not be. He longs for his runaway brother, for his mother to be well, to be normal. Later, he yearns for the people, friends and family, he has lost in one way or another. How did you discover Milo? I wonder if you have other characters you’ve read that might have influenced his forming?

Davis: Milo came to me in drips and drabs. When I first started thinking of him, I was in my early 30’s and so was he. He talked to me like a drinking buddy, full of good cheer and fun stories. In my mind, he seemed a little scarred but basically well-adjusted. I saw him as a conduit to his group of friends. But the story wasn’t working. I got about 200 pages into his story and realized it felt lifeless. Whenever he and his friends talked about their childhood, the story suddenly felt alive, like they had some secret they were keeping. I finally decided I had to deal with that time when they were kids head-on.

Suddenly, Milo wasn’t a conduit to a group of friends anymore—his hardships were the story. I still saw him as the same jokey, hardscrabble guy I’d known before, but suddenly his story was a tragedy. He was a kid dealing with these godawful hardships. Meanwhile, he’s joking through them. To me, it seemed natural, but some early readers saw this kid submerged in darkness. As far as I was concerned, he jokes about his tragedy because people joke about everything. Almost everyone surviving in adulthood has dealt with tragedy, and we all, at times, think it’s hysterical. I’ve had many generations of him in my mind, so he’s not scared to get into the meat and gravy of his misery.

One of my favorite stories is Mark Richard’s “Strays” about two kids abandoned by their parents, having to answer to their Uncle Trash. They wind up burning their house down, and in the summary of events, it sounds tragic. But the story is hysterical and hopeful and makes me want to scream with joy. I don’t know Mark Richard’s thought process, but he grew up in hospitals with one leg longer than the other. No doubt a child grabbing the reigns on his own circumstances would appeal to him. It’s grim, but it’s also wish fulfillment.

McNair: When Milo finds a baby in the backseat of a car he steals, he conceives of a way to try to return the child to safety. However, he is haunted by the baby, by the way he felt in his arms, held close to his chest. Much of this story has to do with parenting: Milo’s mother is very ill and dies midway through the novel, his buddy Meander’s father dies. There is another mother who has a failed relationship with her son, a boy who may or may not have been “played with” at a party held by one of Milo’s friends. Did you know as you started this story that so much of it would have to do with absent parents, with children and parents separated?

Davis: I don’t necessarily think of them as incompetent parents, although, as I say that, I’m unsure how to finish that sentence. They’re self-absorbed to a degree, lost in their own stories, and consumed with their own pain, and they bring that element to their parenting. So, yes, I guess, kind of bad parents. Until you asked this question, I don’t think I realized how much the notion of parenting—present and absent—hangs over this book. It makes sense. About twelve hours after I finished the first draft—which was over twice as long, and quite a different book—my wife went into labor. When I first envisioned a few of these characters, I was a bachelor, living in Baltimore. When the story started to form for real, I was married, living in Kentucky. Then once the characters approached their endgame, I knew fatherhood was imminent. It doesn’t exactly change the story, but, then again, how could it not?

Let me go ahead and say what you’re already thinking: there is a place in hell for all parents who talk about how people without kids can’t possibly understand the emotional depths of the world. I agree. I can’t believe how many otherwise sensible people say, “As someone with a ten year old, I find pedophilia disgusting.” Like people are saying, “As someone with no children, I find pedophilia hilarious.” We have imagination and empathy—the childless, like everyone else, can put themselves in strange situations.

Still, as I re-entered the book, the perspective had changed. The mother dying of dementia no longer felt like a tragedy for the son—it was a new level of pain for the mother as well. Milo rescuing a child from a car he stole started out as the most bizarre comet out of the blue that could hit him. Now I was thinking about what it would take for a mother to leave a child in an unattended car. It helped give me empathy for the parents, which I should have had more either way. I thought of these as comedic situations, but suddenly they felt more human.

Take the scene where Milo’s best friend’s father dies. It started as an exercise where I imagined a character taking a metric ton of acid, and, as he’s waiting for it to kick in, he gets the worst news he can: his father’s dying and he needs to deal with his extended family That’s a (kind of) funny situation, but when the confrontation happens, it’s not funny. The family understands he’s a kid in trouble and they treat him with kindness. Life feels comedic to me, but the harshness often blows it away. I wanted this book to show the spirit of forgiveness.

McNair: Speaking of what you knew when you started the novel, and how that shifted through the writing and re-entering (as you say), there are a few major mysteries in the story: what really happened to Otto, the boy at the friend’s party; where did Aaron, Milo’s brother disappear to; who is Nightwolf, a notorious tagger, really? These questions give rise to others in relation to them as well. I thought it was interesting how Milo changed his mind regularly about what he thought the answers to these questions might be. What’s that old writerly adage? No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader or something? I wonder if you knew the definitive answers to these mysteries at any time, or did it shift for you as well? Perhaps even now you may not know for sure what happened to Otto, to Aaron, and who is Nightwolf.

Davis: There’s no less satisfying answer to any of the questions than “I don’t know, so it’s up to you.” But I don’t know. Or rather, I don’t know exactly. This book is, in part, about the unknown—the way that there are major mysteries that drive us that we will never solve. The point is, we search, and by searching, we generate stories.

These characters first appeared in a story called “No More Chatter” that revolved around a mystery. Milo, now thirty, was dating a married woman and while she was away, he breaks into her house, not to take anything, just to sit there for a minute. He leaves undetected, but the next day, he finds out that someone else had broken in after him and trashed all of the furniture. I never had any desire or interest to solve that mystery and figure out who broke into the house. The story was published, and I was happy with it. Then one woman told me she figured out who broke in the house, and she laid out the reason why. I tried telling her it didn’t matter, but she kept going. It was pretty annoying because she was right. I genuinely didn’t know the answer, but an answer existed below my detection. So I’m absolutely genuine when I say my reading is not a definitive one.

Fair enough, but it’s also a cop-out. If you ask someone whether God exists, there are a million intelligent, complicated, valuable answers, but you want to hear “yes” or “no.” So while, I don’t know exactly, here are my best guesses: Otto was most likely not molested by Thomas the Prophet. At the time, Otto doesn’t seem to think anything happened. But as his situation becomes more desperate, he loses any sense of surety that he had. He might have seen something that disturbed him, maybe was touched, but I doubt it was by Thomas. There’s nothing in Thomas’s nature that would indicate that. The accusations are all vague, and no one ever specifically says what they think happened. I do think Thomas endangered Otto: he let him in the house and didn’t take care of him. Thomas was caught up in the excitement of those times and forgot there was a child there he had to monitor. But I sincerely doubt he actively harmed him.

Is Nightwolf Milo’s runaway brother? I find the evidence that has convinced Milo of the fact pretty unpersuasive. The odds are that Nightwolf is just some random punk, and Milo’s brother is unobtrusively decomposing somewhere. But just because that’s most likely, it doesn’t mean that’s true. The unlikely happens so often that we usually can’t even be bothered to act surprised. Is it less likely than the rest of what happens to these characters? Is it less believable than the scores of absurd, crazy things that happen to us in our lives? As Milo says toward the end of the book, all it takes for miracles is for you to believe in what you do not believe.

McNair: Let’s talk about humor. How do you know it’s funny? Because there were a number of times when I spit coffee out of my nose reading this, sometimes at inappropriate moments in the story. How, too, do you balance the humor with the horror? Because there are some rather horrible things that happen in these pages, and still I laughed out loud.

Thank you, that means a lot. Humor in literature is hard because humor relies on surprise, and by the time you write something, rewrite it, edit it, sit on it for a year, and reread it, then it’s certainly not surprising. Humor ages poorly because jokesters stand on each other’s shoulders. Whatever shocks you into laughing tomorrow is going to seem tame in a month and it’ll embarrass you by Christmas. Most everyone reading this has left a friend in hysterics, but writing means you have to put the joke on a shelf, strip it of all context, and hope it connects with someone reading it in a different world than you wrote it in. The jokes that age the best are absurd, and that’s helpful, because these characters have an absurd view on life.

How do I separate the humor from the horror? I don’t. Horror, like everything else, contains comedy. That’s not a plea for edgier jokes, just an acknowledgement that people joked on 9/11, they joke through broken limbs, they joke after the cancer diagnosis. Not everybody, of course, but those who do aren’t doing it to mask their pain or to “laugh to keep from crying.” They do it because that’s the honest way they experience life.

McNair: This is a real coming of age narrative. Seventeen-year-old Milo becomes twenty-three-year-old Milo, and he learns a lot about life–good stuff and bad stuff–along the way. Characters on the verge of adulthood are fascinating to me; they know so much and so little at the same time. Why were you drawn to this age for these characters?

Davis: This was never meant to be a book about teenagers. Teenagers are a conglomeration of hormones trying to shape themselves into a passing fashion. So I guess, that’s like older people without the hormones or the excuses. I wanted to write about a group of friends.

The buried story is about Milo trying to understand his friend Shea’s disappearance. Shea vanishes shortly before Milo starts telling this story. He recounts these searches as a young man because he’s not ready to go on his current search. The telling of the story is Milo’s way of gathering himself for the new challenge he has to face.

McNair: Despite the toughness of Milo and other characters, despite their seeming autonomy, the role of friends and friendship is essential to the story. I don’t know what my question is here, but I guess I’d like to hear you talk about this some. Maybe specifically about Meander, Thomas, and Shea.

Davis: At heart, this is a story about people who genuinely care for each other. I’ve heard people assume that Milo and Shea are in love with each other. I think they are, but I don’t know if they are romantically. It’s about a group of friends who like each other, and within that number, four (Milo, Meander, Thomas, and Shea) who, in at least some twisted way, love one another. Thomas and Shea understand it. Meander can’t express it, at least not baldly. Milo comes to understand it through the telling of this story. But at its heart, this is a tribute to the ways lost people love each other.

McNair: You mention in the acknowledgements pages that storytelling was part of your upbringing, part of your family’s way of communicating. Is it this deep connection to storytelling that drew you to writing? Whose stories were you most eager to hear when you were growing up?

Davis: My family is unusual in a lot of ways, but I don’t know that our love of storytelling was one. My mother is a novelist who wrote one of the hundred most banned books of the 90’s. That novel, which is called Sex Education and is dedicated to me, was assigned to my 7th grade class. My mother’s sex book, dedicated to me and disseminated to my classmates, made for a long 7th grade. My father was a producer for a lot of Appalachian documentaries. When I was a child, he’d tell me goodnight stories, but if he tried to read me one, I’d say, “Tell me one from your mouth!” My brother was a storytelling savant from an early age. Once, when I was five or six, I heard my mother talk to her sisters about cynicism, and how she was a cynic, and how the country needed more cynics. I asked my brother what a cynic was, and without hesitation, he said, “Someone who has sex with corpses,” and then just watched as I regarded my family in horror. So my family prized telling stories above most things. Even lies were acceptable if they formed a story.

I don’t think this is particularly unusual. Kids grow up telling stories. While most families don’t have my stories, they have stories that are as strange and valuable as mine.

McNair: What are you reading now? What books are on your nightstand?

Davis: The best book I’ve read in the last year (maybe the last couple years) is The Tsar Of Love and Techno by Anthony Marra. When I finished it, I literally shook my head at how something could be so goddamn good. I just finished Because by Joshua Mensch, which is a memoir done in poetic form where he details his sexual abuse. It’s engaging but an absolute scorcher. I listened to the audio of Anthony DeCurtis’s biography of Lou Reed, and I’m about halfway through Jennifer Egan’s Manhattan Beach. Up next is The Third Hotel from one of my favorite contemporary writers, Laura Van Den Berg.

McNair: Would you like to tell us about what you are working on next?

Davis: I’ve been poking around a couple of characters and see how they form together in a story. I have an idea about the son of a famous country musician, a man married to two women at the same time, and a boy who realizes his birthday is exactly nine months after 9/11 and he therefore hates his parents. I don’t know if these characters will come together. I had an idea of writing a full-on love story for no other reason than I don’t think I can do it. Then again, Nightwolf started as a light comedy that kept getting darker, so what do I know?

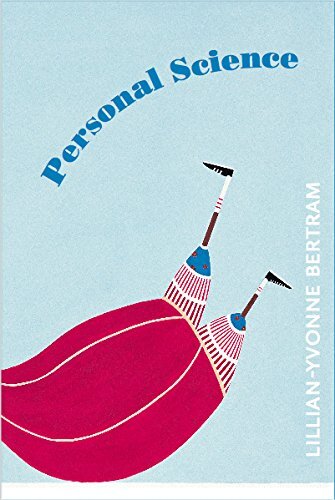

Do It Like This: Personal Science by Lillian-Yvonne Bertram

Lillian-Yvonne Bertram’s Personal Science opens with a problem, posed in the poem “A little tether”: “A self being an object, I can construct / the object I am trying to get to / Refer to the page / But when left, the page fades to pinks and yellows.” The speaker of the poem — Bertram or a version — tells us both what her collection will try to do (construct a self on the page), and that that effort will inevitably fall short:

Lillian-Yvonne Bertram’s Personal Science opens with a problem, posed in the poem “A little tether”: “A self being an object, I can construct / the object I am trying to get to / Refer to the page / But when left, the page fades to pinks and yellows.” The speaker of the poem — Bertram or a version — tells us both what her collection will try to do (construct a self on the page), and that that effort will inevitably fall short: “The thing is just what’s said / The line I try to get to / There are rules even for dreams / The cars are always cars I’ve driven / The men men I’ve known.” The negative space created by this admission is overwhelming; it feels shiveringly, deliciously illicit — a secret revealed, or a power move flawlessly executed, or both. It’s also maddening given that the Self she pieces together in the twenty-four poems of this collection is breathtakingly rich, vivid, and human.

It begins with a series of “Legends like these I keep keeping” poems, which precisely and lyrically conjure the nothing-everything moments of female friendship, spun out of quiet moments between and around the tough shit we cannot escape, and must share with each other (there are rules for dreams). In the “homo narrans” poems we get these luminous little human moments around the meanings we construct and the way they break down: “I worry about hurting the turkey & I find I cannot harm an animal I do not understand,” the narrator of one says while admitting complicity in her companion throwing rocks at it a breath later; “A man walks over and because he looks like the stud on the cover of a romance novel — not to dark but not too light — I figure he’s the gardener.” says the speaker of another. These are precisely the kind of dirty-delicious insights into what is often (pompously) called the human condition which satisfy.

The pace quickens through the series of smaller poems which form “Cerebrum corpus monstrum” on the power of the startling turns and juxtapositions in the images and ideas, and by the growing mood of a searching — or a yearning — building in the collection: “Shining. Alone on a road through Texas, following / The dips of a hawk you let the car weave across lanes / & nothing happened but the hawk kept flying away. / though it was infinite & became but hallucination / You bear all this.” And, like the hawk which soars and then dips, Bertram’s flights of language never stray too far without returning to the real and the grounded. Later in the same poem, the speaker says of a conversation with her brother: “I tell him psychic unease. / Sounds like procrastination he says. You should cultivate / A more productive trait. / Take tenacity, for instance.” Which is exactly the sort of dry thing siblings might say to one another.

The longest piece in the collection is “Forecast” — a prose poem in this context, or perhaps just particularly poetic prose; the distinctions blur. The voice — the Self — is most vivid in this piece, which is stunning and original. It is written in third person, but is brought close by an intensely relatable style of stream-of-consciousness and mode of free association. The subject of the poem — always only “she” — checks forecast after forecast, for her area, the region, the country; she refreshes the page and checks again, checks averages, checks patterns, checks a day out and week out month out. The revolutions around the forecasts resolve in to forecasts for Italy, and thoughts about what to pack — aha, she is going on a trip — which zag away, “Suddenly she remembered a package of breakfast sausage that had been in the freezer for months and was, last she checked, completely frost bitten. She got up to throw it out.” Without losing the thread of forecasts, the piece’s protagonist goes on to worry the themes of what she will do if there is a terrorist on the plane, the concept of the bystander effect, Kitty Genovese, the first full loss in aviation history, a plane crash in Buffalo where she went to college, the aviation concept of the deep stall, making paper airplanes as a child, birds in flight, an old boyfriend who used to deliberately drive fast when was angry, more forecasts, the 1993 “storm of the century”, explosive decompression, Japan Airlines flight 123, her knee problems and the orthopedic surgeon. Then —

“What are you doing, he asked, as he passed through the room on his way to the kitchen. She quickly clicked away from the injury reports gathered around a downed China Airlines flight… She struggled to catch her breath. Nothing, she said, as he was leaving the room.”

Ah, the familiar animal panic of being discovered down an internet rabbit hole.

The poem goes on, and she remembers a time she was delayed due to a mechanical malfunction, she takes some more pills for her anxiety because she is worried they will wear off before she boards (here, her thoughts take on an even more dreamlike timbre), she obsesses over the weather, she digs in to forums of conspiracy theories about the missing Air France flight, she researches all the things that can go wrong on a plane, she checks the maintenance records of the fleet she will be flying. Softly and suddenly, without fanfare because the piece is not about the journey, she is in Milan at her brother’s apartment and pouring over the news about the tsunami, the Fukushima plant, Libya, the bombing of Pan Am flight 103, Gaddafi, radiation spread patterns; ending helplessly: “The only safe place to be was in a plane.” The poem is devastating, incisive, true. It is also one of the pieces which most strongly demonstrates the way in which Bertram weaves scientific, historical, and philosophical concepts into her poems to make them richer.

The collection moves in to the final act, going from strength to strength. “Homo narrans (transplant)” haunts with the image of a transplanted heart wrapped in a papier-maché of dollar bills. “Homo narrans (sustenance)” is a treat, entirely written as a footnote on the subject of a post-apocalyptic existence under an otherwise blank page. The phrase “Like a teratoma whose nails will not stop growing / my life gnaws at me.” from “Psychomanteum” gnaws at the reader from the page; as does “So we read the prehistoric findings. / Nothing hidden in the flesh / but the bone eating its way out.” from the brilliantly titled “Crypsisssssssssssssssss.” There is a distilled genius in “Homo narrans (tongue)” with lines like: “I bite off my tongue to / keep the illness from / spreading its ugly baby. / To tie off what remains I / twist the end tights as a / sausage.”

The final poem in Bertram’s collection (“Homo narrans (Do it like this)”) is a wonderful, terrible dream (there are rules for dreams). The “I” — the Self — of the poem is in a library, looking for her parents who have gone; the library is a plane; the plane has taken off: “The librarian / instructs us / to look forward, / hold our arms / overhead like children on a roller / coaster. Her smile / widens from the forehead / to the jaw. She demonstrates / as the plane pitches, yaws / & dives. Watch me. She says / See? Do it like this.“

Blue Honey by Beth Copeland

Poet Beth Copeland grants her readers full access to her life, loss, and love in the new collection Blue Honey, winner of the 2017 Dogfish Head Poetry Prize. Each poem is deeply personal, giving honest, heartbreaking snapshots of how she lost her parents told through moments from her childhood, marriage, and parents’ battles with dementia.

Nothing is harder than losing the ones we love. And losing them in slow-motion, watching the persons they were disappear in their own bodies — “the long / goodbye” — is a harrowing process. Poet Beth Copeland grants her readers full access to her life, loss, and love in the new collection Blue Honey, winner of the 2017 Dogfish Head Poetry Prize. Each poem is deeply personal, giving honest, heartbreaking snapshots of how she lost her parents told through moments from her childhood, marriage, and parents’ battles with dementia.

Primarily told through a reflective lens, the poems of Copeland’s childhood show her spirited, adventurous parents before their abilities were lost to Alzheimer’s. Missionaries in Japan, there are stories of her parents’ cross-ocean voyages which help contextualize the deep loss of personal identity experienced through their battles with dementia. These journeys also serve as haunting analogies for the final one they are on: “When I ask / where he went, he blinks as if / returning from another / hemisphere into daylight, still / adrift between this continent / and the next.” The juxtaposition of the tragic late-life realities with the vibrance of youth are heartbreaking. Copeland writes, “When / I was small . . . I believed / he could hold back / time forever, a pulse that / would never stop” — a painful illusion one learns the truths about with time.

Copeland’s honesty throughout the collection is moving and purposeful. It gives a thoughtful and balanced reflection on the challenges and frustrations of mental-faculty loss for both the afflicted and the loved ones watching the disease take hold. We are shown her father’s struggles to speak and swallow, as well as her mother’s rapid memory loss. Towards the end of her life, her mother would quickly forget things she’d just done or said. Her mind refreshes and repeats. Copeland’s love and sympathy are well highlighted, but she doesn’t sugarcoat the challenge: “I want / to talk to her, but I want / to hang up, too, after listening to her / refrain like grooves on vinyl.”

The difficulties of Copeland’s own marriage, seen in poems such as “Cleave” and “Sweet Basil,” show not just the tolls losing one’s parents can have on our relationships with others—“Is this pairing of pain / and passion the moon’s / push-pull”—but also help contextualize the miracle that was her parents 66-year relationship and the agony of watching their lives now. Copeland articulates the situation with gut-wrenching honesty: “I love them but want / the blade to drop / the bleeding to stop.”

Each expertly crafted poem is beautiful-written but accessible. Together, the poems give a clear window into Copeland’s memories, experiences, and thinking. They show the grim realities of Alzheimer’s destructive powers. But these incredible poems also show that even in the worst of circumstances not everything is lost. “A mother’s love never vanishes,” Copeland writes, “fixed as / the North Star with no stops in a midnight sky.” Disease can take away mind and body, but it can’t take away love: “I hold / her in the heart / of my heart / where she’s whole.” Pain and sadness are inescapable realities of this world, but Blue Honey grants us the necessary reminder that there is so much more.

Between a Droplet and a Deluge: On Michael T. Young's The Infinite Doctrine of Water

The Infinite Doctrine of Water, by Michael T. Young, explores contradictions that trouble and enrich our lives. While water is essential, floods can kill. This collection also brings to light the extraordinary; the poet teases out insights that a lesser mind would ignore.

The Infinite Doctrine of Water, by Michael T. Young, explores contradictions that trouble and enrich our lives. While water is essential, floods can kill. This collection also brings to light the extraordinary; the poet teases out insights that a lesser mind would ignore. His humanity and ability to observe guides the reader through paradoxes, ultimately finding them redemptive.

The collection opens with a sonnet-like gesture, “Advice from a Bat.” Written in second-person, it shows there is much to admire and learn from this macabre creature, recalling Roethke’s “The Bat.” Young’s poem, however, becomes an ars poetica: “Retreat to a cave no one believes in.” In other words, dare to write in an aesthetic that may not be popular; embrace a position that is not widely championed. Be authentic. This advice serves Young well.

Reminiscent of The Metamorphosis, transformations populate these pages. A mythic tone informs “Molting,” “Sometimes she can feel her wings growing.” What we encounter in the poems shimmers, dissolves, and changes as we read them.

The reader can also see a Keatsian negative capability. Young accesses this position as an extension of his openness to experience. He’s receptive to comprehend, and therefore, to grow. He writes, “It’s the nameless power of its bark / that arches over me where I sit / gnawing its roots and curiosities, / growing stronger with hunger.” Indeed, a “nameless power” surges through Young’s cadenced words, which contain another paradox—that hunger can nurture.

A philosophical yearning emerges. In “The Reservoir,” Young asserts, “For years people slaked their thirst / at the source of things.” Longing, call it nostos, propels this collection, as if the poet is aching to return to “the endless blue into which they expanded.”

Another poet who wrote of bodies of water as symbols for time, the unknowable, and the inexorable was Elizabeth Bishop. She was once quoted as saying that she wasn’t writing about thought, but about a mind thinking. Similarly, Young brings us into the process of his thought. His cognitive leaps work as metaphors, proffered to the discerning reader. For example, in “Bioluminescence,” we begin with Rembrandt’s Philosopher in Meditation and end with a fish that emits light in the ocean’s “perpetual night.” Similar to Rembrandt’s use of paint, Young is writing chiaroscuro. He delves into the depths of human darkness to encounter light. Sometimes it eludes him.

“Hungry ambivalence” follows this poet who lives in and a part from the world through his piercingly accurate perceptions of it. He opens the poem “Treading Water” by peering at the Hudson, a body of water that appears to be both beginning and end (fusing and reconciling contradictions). Young is mapping an ontological conundrum. But instead of turning from it, he makes room for ambiguity. Young states, “[C]urrents / … wagging at the fluidity / of the historic, the generosity of chance.” Here again is the poet’s humanity, acknowledging the vicissitudes of fate.

In “After Rain,” we read, “[N]othing profound is safe. That’s why / its chasms are hoarded or pawned in each drop.” A melancholy quality emanates from some of the poems. In them, Young leans towards a more idyllic reality, one that exceeds human understanding, “beyond reach and comprehension.”

“Like Rain” tells us, “[T]he way it all seems to rise and write itself in the hot summer air, / a suggestion of wings and ethereal choirs.” Here’s an example of Young’s attention not only to the what of poetry but also to its how. Never is there so much as an excessive syllable, for this poet knows that in order to penetrate the reader’s unconscious, in order to enter deeper realms, a poem must sing—be it a chant, a lament, or a canticle of exaltation. To be sure, each phrase is musical, even psalmic. Each phrase is a current in an underground river, coursing from poem to poem, arriving at “The Voice of Water.” Young concludes, “Even after you’ve closed the book, / it keeps reciting the lines.” These lines will resound in our minds long after reading this necessary collection.